The EU as Last-Ditch Escape Artist

The EU as Last-Ditch Escape Artist

LONDON: Europe’s progress towards greater unity over the past half century has always been a messy business, marked by recurrent warnings of collapse followed by compromises that fully satisfy nobody but keep the show on the road. So why is the 40-month old eurozone crisis any different? With the embarrassing case of Cyprus handled, won’t this all end with yet another patched-together solution?

The answer is probably, no, and the ramifications of what is happening reach far beyond the kind of late-night settlements which European leaders have been so adept at cobbling together in the past. The crisis that started with Greece’s 2009 disclosure of a black hole in its budget is broader in scope and more interconnected from what went on before. The eurocrisis involves fundamental issues which European leaders skirted as the Common Market trading block of the 1950s evolved into today’s highly complex machine based on Brussels with a common currency that remains a work in progress.

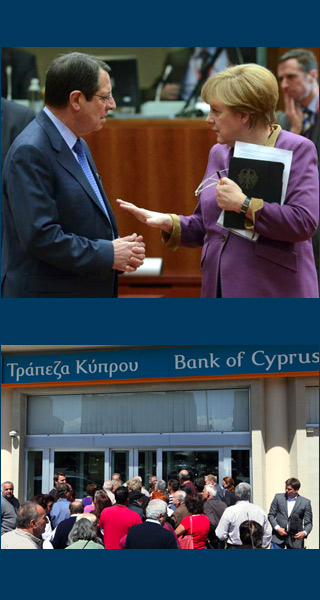

Cyprus was dealt with, for the moment at least, by the kind of draconian measures which powerful members can impose on a small, weak member of their club. Without the last-minute settlement reached in the early hours of 25 March, the island would have been bust, abandoned not only by its European partners but also by the Russians who had taken advantage of the lax banking regulations to put their money in its banks. So the country must now pay the price with austerity, the closing of one big bank and the restructuring of another plus levies on bank savings that will destroy dreams of a would-be thriving off-shore financial center and leave those with the largest deposits much worse off.

So far, governments have taken the hit for bailing out countries in trouble, starting with Greece. But the penalty applied in the case of Cyprus at the behest of Brussels and Europe’s prime economic power, Germany, has opened a new avenue of pain as private investors found themselves contributing, whether they wished to or not, as part of the rescue package while the imposition of capital controls made nonsense of free circulation of cash within the currency zone.

Jeroen Dijsselbloem, the Dutch head of the Eurogroup, a formal intergovernment organization of the zone's finance ministers, then upped the stakes by saying that this would set a model for the future. Shareholders in insolvent banks in countries needing rescue would be hit first followed by bondholders and uninsured depositors. Though Dijsselbloem swiftly withdrew that statement, the future seems plain as other smaller eurozone members come under scrutiny and investors face the prospect of finding their capital expropriated as the result of decisions by politicians desperate to prevent the common currency from unraveling. Riding the tide of cheap money flowing from quantitative easing, markets have taken this calmly, but, if similar medicine was applied to a bigger country, the rush for the door could turn into a stampede.

The make-it-up-as-you-go-along style applied through the crisis, and most evident in the shambolic handling of Cyprus, is all the more dangerous because of the context surrounding the common currency.

Spain’s central bank last week forecast a 1.5 percent contraction of the economy this year with unemployment set to hit 27 percent. Italy’s economy shrank by 0.9 percent in the last quarter of 2012 and the ratings agency Fitch has downgraded the country to two notches above junk status. Data issued last week showed that France’s GDP fell by 0.3 percent in the last quarter and the Socialist administration of François Hollande, which took office 10 months ago on the promise of creating growth, has failed either to reduce the deficit, which will exceed the 3 percent target agreed with the European Commission for the end of this year, or to cut public debt which rose to a record 90.2 percent of GDP in 2012.

Britain, outside the eurozone but in the European Union, is fighting to avoid recession with growth down 0.3 percent in the last three months of last year. At last, the German economy is forecast to continue to put in a strong performance this year with the OECD last week predicting growth of between 2.3 and 2.6 percent for the year, but there was a tremor even in Europe’s economic powerhouse when growth contracted in the last quarter of 2012.

Given the commitment to austerity to get the continent out of its troubles, as adopted by its leaders, it’s hard to see a significant overall pickup in economic expansion; even President Hollande, the great growth advocate, is promising spending cuts. That will increase the already high level of unemployment in many of the zone’s larger members as the public sector is slimmed down and companies hold back from investment or remodel their businesses to become more competitive with fewer staff. The need for structural reform, including labor markets, has been evident for decades, but the easy early years of the eurozone lulled governments and citizens into complacency.

Now the price is being paid and the battle lines are drawn between the austerity-minded north European states, generally in good shape, and their southern partners, which are not. Political factors now come into play in some of the continent’s biggest nations. Italy is in the grips of a governmental crisis after inconclusive elections. Hollande is at a record low in the polls and failed to deliver a convincing message in a major television interview last week. Spain’s ruling party is accused of involvement in a funding scandal.

With federal elections later this year, the continent’s strong woman, Angela Merkel, cannot afford to offer concessions that German voters would see as pandering to countries which, in their view, have already been allowed to get away with fecklessness for far too long. Extremist parties and movements that denounce the political establishment have made ground in Italy and Greece while a quarter of the electorate opted for anti-European candidates in the first round of last year’s French presidential election.

Behind such immediate problems lurks the fundamental question of whether the construction of the eurozone can be completed by the fiscal union it requires to operate as a true common currency. That would involve a surrender of sovereignty, which would stick in the throat of some states, starting with France. The balance of power means that advancing the process that began with the Treaty of Rome in 1957 would inevitably be done on terms set by Germany and its economically strong allies in northern Europe. That would be difficult to resolve by the kind of muddling through we have seen in the current crisis. So far, politicians may congratulate themselves on having engineered a series of last-ditch escapes, but the longer this goes on, the more difficult it will be to keep up the act.