Europe Faces Globalization – Part I

Europe Faces Globalization – Part I

PARIS: Call it the French paradox. French multinationals go on acquiring foreign assets, but the French government is busy erecting walls around French companies against foreign takeover, while at the same time encouraging foreign investment in the country.

France appears as the most protectionist member of an increasingly protectionist Europe, following a succession of government interventions against attempted takeovers of French companies by foreign interests: Paris foiled the acquisition of the Danone Group, maker of yogurt and mineral water, by the American giant Pepsico; publicly opposed the buying of steelmaker Arcelor by Anglo-Indian Mittal Steel; and pushed for the recent merger between water utility company Suez and the national gas company GdF to prevent Suez becoming prey to the Italian energy concern Enel.

Prime Minister Dominique de Villepin has repeatedly intervened to stop cross-border mergers as official policy, under the label of “economic patriotism.” His government recently introduced legislation designed to complicate, or just block, hostile takeovers of French companies in eleven sectors deemed as strategic to the economy. The government has drafted a list of ten major companies from the CAC 40 index of the Paris Bourse as untouchable by foreigners. Not yet published, the draft is said to include distribution giant Carrefour, the Société Générale bank, Danone and glass-maker Saint-Gobain.

Meanwhile, in April the French electronics company Alcatel absorbed American telecom equipment maker Lucent, the latest in a long list of mergers and acquisitions by French groups – 190 last year, a 157 percent increase over the previous year, for a record €60.6 billion. Such activity suggests France is practicing globalization à la carte – profiting from globalization while resisting others’ efforts to do the same with French companies, along the principle, “What’s mine is mine, and what’s yours is open to negotiations.”

While France may be more open in applying this double standard in the globalization game, it is far from alone. Since the beginning of the year, Spain has blocked a German company taking over one of its own energy producers; Poland has thwarted the purchase of several of its banks by Italians, while Italy has done the same for some time, as evidenced by the long-running battle in 2005 to fight off the takeover of Antonveneta bank by the Dutch bank giant ABN Amro; and Germany staunchly defends its “Volkswagen law,” protecting its auto industry from foreign predators.

Outside the EU, one need only look at the spat over the acquisition of six US port operations of P&O by Dubai Ports World or remember the furor over the Chinese oil firm CNOOC attempting to buy Unocal. This list, not exhaustive by any means, shows that what the French call “economic patriotism” is a truly a globalized attitude, especially in the developed world. Ironically, the developed nations push for more liberalization and opening of investments against developing powerhouses like China, India or Brazil – which resist the opening of their still highly state-controlled and “national” economies – in the Doha Round of international trade negotiations.

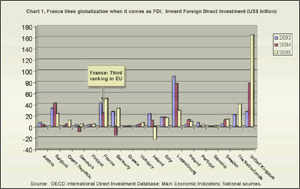

Economic patriotism may strike some as odd and incoherent when considering that its leading proponent, France, is by far the EU nation most “open” to foreign investments, at least according to IMF figures. Direct foreign investment represents 13 percent of GDP in Italy, 25 percent in Germany, 36 percent in the UK – but 42 percent in France. Over 40 percent of the shares of the most important French groups quoted on the Paris Bourse are in foreign hands, and one in seven French workers is employed by a foreign company – compared with one in ten in the UK and one in twenty in the US. But in France, economic patriotism has deep historical roots, right to the birth of the modern French state in the 17th century, under Louis XIV and his Prime Minister Jean Baptiste Colbert.

The state’s political legitimacy was predicated upon its capacity to macro-manage the economy, lead a successful development strategy, launch big industrial and technological projects, and nurture world-class “industrial champions.” This endured into the 20th century, successively upheld by the Left – the Popular Front government nationalizing in 1936 defense industries, railways, the Banque de France and more – as well as the Right, with Charles de Gaulle doing much the same after 1945 for the nuclear, aeronautics, railways and space industries. To this day, French minds link the “Thirty Glorious Years” of the post-war French economic miracle with this policy. Economic patriotism is thus as much a political as an economic concept.

At a time when the public views the national state and its politicians as weakened and made powerless by globalization – a phenomenon so far exclusively driven by economic and, more and more, financial forces – economic patriotism has been rediscovered as an antidote to skepticism and distrust of political leaders. Public opinion polls show that 69 percent of the French favor this policy.

Then again, economic patriotism is not a peculiarly French reaction to globalization, and other forces must be at work. One is the current crisis of the EU. Since last year’s French and Dutch rejection of the proposed European Constitution, previous attempts, many halfhearted, at European industrial policies and cooperation, and dreams of “Europe as Power” are at a standstill. At the same time, the deregulation of key European markets has generated a frenzy of mergers and acquisitions unseen since 2000. Governments have consequently acted along their own perceived “national interests,” pressured by their citizens anxious about the social costs of deregulation and the loss of decision-making in foreign buyouts.

Many people – again not only in France – are unconvinced that, in line with liberal ideology, only the benevolent and cosmopolitan “hidden hand” of free markets is at work in international economic dealings. One of the ironies of economic patriotism is that the French advocates have theorized that it’s taking a leaf from Washington’s book. They point to American supporting and protecting key industries and technologies through devices such as the Advocacy Center, set up by the Commerce Department in Washington, DC, to “support and expand” US exports; the Committee on Foreign Investment in the US; the Exxon-Florio legislation; or federal control over some investment funds, like the CIA-created In-Q-Tel.

Alain Juillet – former deputy head of the French secret service Direction Générale de la Sécurité Extérieure, whom Prime Minister Villepin has placed in charge of “economic intelligence” – argues that “we in Europe are in fact much more liberal than the United States” in matters of political control over strategic companies. Proponents of economic patriotism argue that, in the post-Cold War world, technological and economic competition has become paramount, not only for security, but also for diplomacy, politics and social benefits. “Economic patriotism is a thoroughly modern concept,” according to Thierry Breton, former head of France Telecom and French minister for the economy, finance and industry.

All things considered, the paradox one finds in French policies on foreign investment is a generalized one. For all their talk of letting the market decide, the developed countries are just as quick as developing ones to raise walls when they think their national interest may be affected or for reasons of domestic political expediency. “Economic patriotism” is the flip side of free-market liberalism and part of the current fashion for globalization à la carte.

Patrick Sabatier is deputy editor of the Paris daily “Liberation.”