In Europe, North Battles South

In Europe, North Battles South

SINGAPORE: As Greece struggles with its debt crisis, a growing chorus favors leaving the euro and devaluing the drachma. This focus on a single currency masks the real problem for the eurozone: Pressures of globalization have exposed two economic models within the zone – one embraced by Europe’s north and the other in the south.

Reluctant to embrace painful reforms, some in Greece regard devaluing the currency an easier solution. Devaluation may bring immediate relief, but would sap the country’s economic strength. Economic reform proposed by northern European countries promises higher growth in the longer term, but pain and sacrifices now.

The clash between the northern and southern models is shaping up in the forthcoming presidential election in France. In many ways France is a microcosm of the eurozone with an economy and a societal structure reflecting both the efficient northern economies and the southern non-competitive ones. Underlying the programs presented by President Nicolas Sarkozy and Socialist challenger François Hollande is the contest between an old-fashioned, less malleable structure found in the southern tier of the European Union and the model successfully used by Germany.

The election’s outcome may indicate which way European citizens want to go. German Chancellor Angela Merkel senses this, which explains why she has openly, strongly supported Sarkozy. He’s trying to change course, get into the German lane and pull southern Europe along by example. Merkel fears that Hollande, if elected, will spread uncertainty about France’s pledge to reform and in the process roil the entire eurozone.

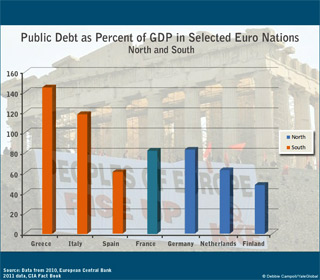

The vast gulf within the eurozone, apparent in recent years, has long been plagued by this dichotomy between northern Europe’s competitive economies, in particular Germany, plus the Netherlands and Denmark, Sweden, Norway, Finland and the southern nation-states epitomized by Greece, but also Italy, Spain and Portugal.

As the rigid, debt-ridden economies of the Mediterranean seaboard have undergone economic shock from the debt crisis, many economists jump to the textbook answer – a hefty devaluation.

Devaluation makes exports cheaper thus boosting volume. Imports fall because import prices go up. Increased exports and falling import stimulate production and employment. Income is redistributed to the advantage of the business sector promoting investment. The trade balance improves. The main disadvantage is that higher import prices reduce real income, making the devaluing country poorer, but it shouldn’t be a surprise. Devaluation is often chosen after a country has lived beyond its means.

Devaluation only delivers if market conditions prevail. Price and wage changes must be allowed to work their way through the economy. And this is precisely not the case for the southern countries. The competitive advantage they gain would be neutralized by rigid rules and license systems designed to prevent changes.

Regulations approved by legislatures make it almost impossible to cut a company’s workforce, so companies hold back on hiring until absolutely sure that future economic growth supports a higher workforce. They resist repeating mistakes – hiring in good times, then forced to soldier on during bad times, with a high wage bill eating into profits and investment.

Large parts of the economy – trucking, legal services and pharmacies, just to mention a few examples – are shielded from market forces by license systems, particularly damaging when distributed in corrupt ways, including favors or kickbacks. Limiting licenses allow owners to charge high prices for the services and pass some revenue on to government agencies. Greece’s freight-transport industry is dominated by 33,000 trucking licenses, with the newest dating back to 1970. The licenses trade for as high as $400,000. Such a system penalizes the competitive part of the economy and rewards the non-competitive, creating a market barrier and slowing growth. Prohibitively high transport costs hike food prices leading to wage demands in urban areas, thus hollowing out competitiveness.So tomatoes grown in Dutch greenhouses and shipped from Rotterdam compete with home-grown tomatoes on the shelves of Greek supermarkets. And when organizing an event on the Greek island of Corfu, the Greek International Chamber of Commerce saved costs by renting tables and chairs from Brindisi in Italy than bringing them from Athens.

The Southern European countries have run such economic systems far too long. Greek citizens can retire with pensions at age 53. And on the World Bank ranking for ease of doing business, Italy is 87, just after Zambia, the Bahamas and Mongolia; Greece is number 100; Germany, Denmark, Sweden, Finland and Norway are ranked among the top 20.

Leaving the eurozone could bring only temporary relief for Greece. Its best chance is to stay in the eurozone and tackle structural changes now with financial support and advice of other member states and the International Monetary Fund. If Greece and other southern states quit the euro or procrastinate, they could slide into an abyss with no one willing to offer rescue.

The northern tier runs more flexible, competitive economies with higher mobility. Northern Europe invented flexicurity, a pro-active labor market policy, with flexibility emphasized through retraining, lifelong education and systematic efforts to develop new employment opportunities. Security in the form of allowances is linked to schemes for re-employment.

But the northern countries, too, must bring welfare expenditures under control. For a number of eurozone members, including France and Germany, welfare expenditures are well above 30 percent of gross domestic product – as compared to 19.4 percent in the US and 25.9 percent in Britain. Such expenditures are not sustainable with a low growth decade ahead, even more so as some of the money flowing into schemes blocks flexibility and mobility in the labor market.

Europe’s attempt to trim its welfare state to sustainable levels may be the biggest and most daring socio-engineering enterprise over the last 50 years. The Europeans must make health and pension benefits fit what they can actually finance instead of amassing claims on future generations. Rather than borrow to pay for such welfare programs, governments must withdraw privileges that were given to citizens during an era with a better economic outlook.

The goal is not to demolish the welfare state, but to trim it, eliminating excesses, exaggerations and aberrations, ensuring a chance at benefits for future generations

It’s imperative for the northern tier to return to a growth pattern to generate funds necessary for financing policies and help the weaker parts of the eurozone. This is the way an economic and monetary union should work.

The alternative is much worse, actually quite dangerous for social and political stability:

The first effect would be for rich northern European countries to abandon the southern nations, opening the doors for political and economic experiments or extremism. History gives ample warnings on the dangers of this path.

The second effect would be, not mere trimming of the welfare state and safeguarding its basic principles, but a near dismantling of a socioeconomic system built over nearly 80 decades, putting its stamp on almost every aspect of daily life in Europe.

Geographically, yes, there would still be something called Europe, but the continent would have a new, unwanted character politically, economically, and socially. And the rest of the world might soon regret the loss of the European welfare state, a model demonstrating concern for every human being.

Joergen Oerstroem Moeller is a senior visiting research fellow with the Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, Singapore Management University, and adjunct professor with Singapore Management University and Copenhagen Business School.