Fawlty Globalisation

Fawlty Globalisation

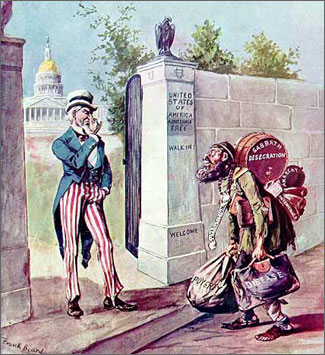

NEW DELHI: Manuel holds the key. You remember Manuel, surely. He was the Spanish waiter in that uproarious BBC television series Fawlty Towers. He was hired by Mr Fawlty, the owner of a British country hotel, for only one reason: because he came cheap. Manuel no speak Inglis; Manuel say si si si si and bring wrong wine; Manuel send Mr Fawlty's nerves into triple fault; Manuel man with heart of gold and hands of brass; Manuel crazy and drive everybody crazy; but speak-no-Inglis Manuel get job in remote English countryside instead of local Englishman under spluttering Mr Fawlty because Manuel come cheap.

That is globalization.

Bitterly divided, constantly warring Europe could never have turned into a dream without giving the underprivileged the right to a job in any partner economy. It was this base that underpinned the larger concepts of political and economic unity. You cannot have globalization without creating space for economic asylum.

There are two recognized forms of asylum. The first, being political, is more politically correct. The world has long recognized the need for political asylum when population groups suffer the misfortune of oppression. Economic asylum has always been more troublesome, because it is considered invasive. After all, by declaration, these are migrants who have come for a part of the economic wealth of the host nation. The human spirit generally finds room for shelter to the political refugee; it is less accommodating towards the economic refugee.

But there is sufficient evidence to prove that a refugee of either kind can actually add to the economic wealth of the host nation. Political refugees are, more often than not, qualitatively better. The Jews brought their skills in banking, trade and scholarship to the Ottoman Empire; just as they later took the same virtues and put them in the service of the American empire. Punjabi and Sindhi Hindus who were driven into India after partition that created Pakistan, quickly became substantive builders of the post-colonial Indian economy. At this moment, the Sri Lanka-Tamil refugees who have taken shelter in India from the civil war are creating a network of businesses: their traditional asset of education is a strong foundation for entrepreneurship.

Economic asylum is tinged with less salubrious factors, with greed and guilt entering the relationship on both sides. Obviously the desire for a better life drives the poor into a richer neighborhood. But there is also the greed of the rich, who want to pay less for the services that the economic refugee offers. The syndrome is the same, whether it is the dhobi (laundry-man) setting up shop in a posh locality in Delhi, or Britain inviting the sweeping (janitor) classes from the old empire in order to keep Heathrow airport clean. Supply and demand easily stretches across national borders. Inevitably, the consequence is cultural tension. Ideally, the rich would relish the use of cheap services, and then ensure that the service-providers went back to where they came from, a slum, or a nation, that is out of sight. That is what Enoch Powell would have liked to have done with the Asians after they had finished cleaning Heathrow. But such wishful thinking does not work in human affairs, although in some cases (like the old South Africa) it can continue for generations. But not forever. Slavery, or cruel forms of inequity like indentured labor, can never last forever. Human beings will rise above their economic origins, and then demand to live according to values that are associated with modern civilized social behavior. Conflict is inevitable, and sensible societies must find the means of conflict resolution. Affluent nations who want the comfort of cheap labor must enlarge their social and political space to integrate such communities, and then provide scope for upward mobility.

This is what the United States has done consistently with refugees, who first came from Europe and then from the rest of the world. The political rationalization of America in the 18th and 19th centuries, through independence and unity, and the defense of both in a civil war, created the momentum, harmony and order that propelled the economic process. Ambition is always a great spur to economic growth, and no one wants a better life more desperately than an economic refugee. The secret of America was simple: it became the ultimate dream of the dispossessed and the disinherited. Immigration was the great powerhouse that drove the American economy to the point where it is seemingly invincible. Every fresh wave of immigration brought the raw power of boiling ambition. You could trace the route map of every wave: first, the street, with jobs in either crime or services like the taxi-trade; then into the factories; then the gentrification; and then the turn of the curve in the parabola, and five-day weeks with pretty homes in the suburbs. It was normally a three-generation process.

India, the potential but unrealized America of the East, has always maintained a generous refugee-regime. It is partly to do with traditional values: the Indian has had little difficulty in finding space for the other, and then, imperceptibly but surely, converting the other into an Indian. But there is a more modern reason as well. The calamity of partition sensitized India to the tragedy of displaced lives. It was a full-blown crisis that could not have been resolved only by the government; it required, and received, the complete cooperation of the people themselves. Modern India faced the challenge of political/economic asylum at its very birth. Fortunately, social integration was not an issue, since the refugees were Hindus who shared the faith and culture of the host nation. But the Indian experience includes a remarkable variation of this theme that is a tribute to something unique in the Indian consciousness. This is the absorption of a huge Muslim migration into Hindu-majority India, from Bangladesh - a country that broke away from Pakistan. The Muslims of Bangladesh are voting against the economically ruinous division of India with their feet. Partition has prevented united India from realizing her true economic potential, and will remain a barrier until the subcontinent becomes a free trade zone.

The unity of India itself is protected by free trade and free movement. India is large enough and disparate enough to be, by itself, a model for the prevalent theories of multinational globalization. In a sense, the makers of the Indian Constitution offered a model which Europe has now applied to its own circumstances, a mixture of local rule by linguistically different communities and a supra-economic structure that is designed for the greater benefit of all. No structure can prevent imbalances, which may arise from the frailties and imponderables of human behavior. If the under-developed state of Bihar has not exploded into a Maoist-type anarchy, of the kind we see in neighboring Nepal for instance, it is because the Bihari below the poverty line can seek to redress his condition by free movement to wherever he can find work, whether in a bakery in Mumbai or a road building work in Kashmir. Without free movement, the Indian union has no economy; and without an economy, India can hardly remain a union.

If globalization is the prevalence of free trade, then it existed before it was called so. India's problem was that it did not extend the principles that had worked so well within India, to its economic relationships outside India. Indians paid a heavy price for this mistake.

But some of the chief votaries of globalization commit an error when they forget that you cannot share wealth without sharing opportunity. Globalization must, in order to succeed, be a composite idea rather than a single-track focus. It is in danger today of becoming synonymous with injustice, and a form of quasi-colonialism. This perception may not be wholly correct, but it is gaining strength on the street because globalization has become the private property of a number of vested interests - multinational corporations and governments of rich nations included. You cannot take natural resources out of a country, even if you pay a notional price for them, and expect the people who once owned the resources not to ask for a share in the rising value chain.

It is welcome therefore that one of the gurus of globalization, Professor Jagdish Bhagwati, argues that "the world needs a World Migration Organization to complete the international superstructure of 'governance'." The WTO can best survive with a WMO as its companion. The professor traverses heights of eloquence when he writes: "As people walk, fly, and swim across borders, as migrants or refugees, fleeing or simply seeking a better life, and their numbers steadily rise, the time has come to address institutionally the ethics and economics of this flow of humanity instead of leaving it to the whims of individual nation-states. Anything less would be a shame."

It would also be a mistake. Remember: Manuel holds the key.

M.J. Akbar is editor of AsianAge and author of numerous books, including The Shade of Swords.