Fighting Words: US and China Clash on Free Speech

Fighting Words: US and China Clash on Free Speech

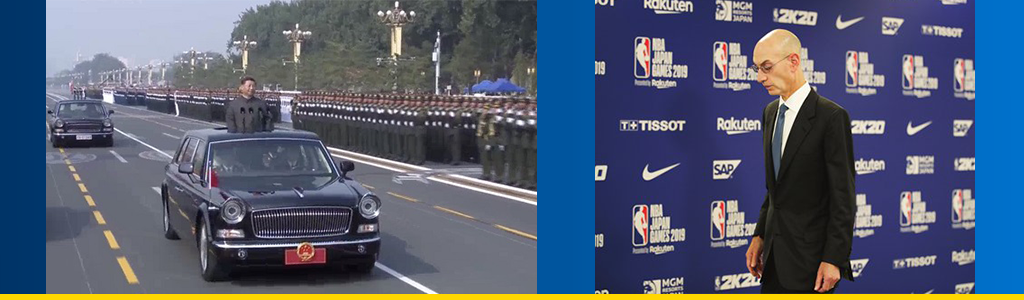

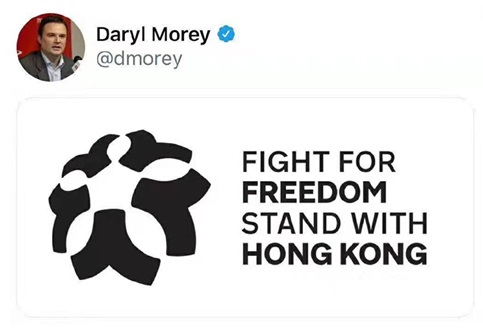

DURHAM: A Twitter post from the general manager of the Houston Rockets of the NBA, endorsed the “fight for freedom” in Hong Kong, threatening more than 15 years of work that went into building a massive fan base and business partnerships for basketball in China.

The short message endorsing freedom exasperated the Leviathan in Beijing. Helpless and powerless as most Chinese citizens may be in “climbing” the Great Firewall to see what Twitter is like, they were mobilized to demonstrate patriotism. Influential Chinese media announced punitive suspension of NBA broadcasts. The “trade-restrictive” measures worked immediately, resulting in a statement of apology in Mandarin from the NBA, though that appeasing act ignited strong criticism of NBA’s trade-off between lucrative profits and free speech among Americans.

For the NBA, such small lip service may seem worthwhile. After all, the Chinese market makes up around 10 percent of NBA gross revenue. With Yao Ming as a former star of the Houston Rockets, the league boasts of a potential audience of 600 million and could enjoy a five-year broadcast contract with Tencent, reported to be worth US$1.5 billion. Such is the price for a short, deadly Tweet, though Chinese fans are more forgetful than the government might prefer: An October 10 exhibition game between the Lakers and the Nets in Shanghai still attracted a large crowd.

This détente may prove transient. During the same week, Apple removed HKmap.live from its App Store. The People’s Daily, official newspaper of China’s Communist Party, accused the controvertible software for “escorting rioters” in Hong Kong, allowing them to track police movements. Typically, state media views such apps as “poisonous” and a “betrayal” of the nation’s collective feeling that the government claims to represent.

In essence, both the NBA and Apple practice the recipe against tyranny, as prescribed by the US founding fathers in the US Constitution and its First Amendment. To achieve this aim, the law ensures, at its core, protection of all political speech even in forms that may barely be identified as peaceful: incitement to violent action, flag burning, slander, libel or hate speech. In a word, US law protects fighting words. If there is anything that may be called Americanism, the overwhelming protection of free speech is definitely among the leading components. In that ultimate sense, all products to be traded with America’s business partners include this element of free speech.

In essence, both the NBA and Apple practice the recipe against tyranny, as prescribed by the US founding fathers in the US Constitution and its First Amendment. To achieve this aim, the law ensures, at its core, protection of all political speech even in forms that may barely be identified as peaceful: incitement to violent action, flag burning, slander, libel or hate speech. In a word, US law protects fighting words. If there is anything that may be called Americanism, the overwhelming protection of free speech is definitely among the leading components. In that ultimate sense, all products to be traded with America’s business partners include this element of free speech.

A fundamental and irreconcilable clash in the Sino-US trade war is between the US First Amendment and the Chinese government’s ruthless policy of suffocating freedom of expression. My previous article for YaleGlobal, China’s Censorship vs. US Free Speech, reviewed the history of trade friction between the two nations dating back to the 19th century when the Qing Dynasty attempted to trade copyright protection of US works for US support of censoring revolutionary thoughts in China. That trade-related ban didn’t work – and the last Chinese empire collapsed only within a few years despite its inexorable efforts of censorship.

More than a century later, the same play goes on stage, and China is far more assertive. Whereas China reneges on its promise to negotiate about the seemingly insurmountable obstacles in the protection of intellectual property – core issues of the ongoing Sino-US trade war – the government’s propaganda machine is in overdrive, attempting to suppress free speech across national borders. Recent trade talks in Washington may bring a ceasefire in this protracted war, yet one cannot expect the clash of political values to ebb as trade tensions ease.

In contrast to the pacific, obsequious attitudes that almost all governments throughout Chinese history have required the nation to have towards the “state,” the protection of political “fighting words” is deeply rooted in American history. In the 1860s, British philosopher John Stuart Mill, in his treatise On Liberty, wrote famously, “If all mankind minus one, were of one opinion, and only one person were of the contrary opinion, mankind would be no more justified in silencing that one person, than he, if he had the power, would be justified in silencing mankind.”

That old assessment marvelously juxtaposes Morey’s fighting words today and the “fighting spirit” that Xi Jinping, China’s chairman, called for in his September address to young officials of the Chinese Communist Party. Xinhua reported, with emphasis, that the word “fight” was used for 58 times in Xi’s talk. Backed by the most pompous military parade since 1949, Xi delivered a speech in memory of the 70th anniversary of the People’s Republic of China and declared to the world that no one could “shake” China today. Given that modern China is so powerful, what is the country fighting for, according to Xi?

Clearly, its fight is not confined to the trade war with the US that China pledges to “fight to the end.” Rather, the trade war is breaking out on a much larger scale than that, as the Chinese party-state is confronted with a series of threats at home and abroad. In the party’s mind, all of these threats could be underpinned by the exercise of one’s right to freedom of expression. Above all, the party fears that the threat to its absolutist rule may still be embedded in the body of its own functionaries. On October 8, China published a draft bill on the punishment of civil servants who dare express opposition openly to party leadership or socialism, be it in the form of articles, speeches, statements, assemblies, demonstrations or strikes.

Hong Kong’s protests since June have produced a butterfly effect around the world. The party feels urgency in fighting against threats in Hong Kong, where a law bans people from wearing masks in the public, thus creating a chilling effect on speech or acts that the government deems inappropriate or irresponsible. Under international law, however, excessive restriction of speech requires ample evidence for its necessity. The threats also come from overseas trade partners. Multinational companies that rely on the Chinese market are, as a matter of fact, bound by the party’s ideological control. Under the aegis of China’s nationalism, restriction of freedom of expression has permeated almost all industrial and commercial sectors.

The NBA case shows the kernel risk of thrusting oneself into the Chinese market: China has learned to weaponize its market. Thus, a Sino-US trade deal, even if it may well be envisioned in the leadership’s goodwill to reach a truce, could be shredded due to incompatibility between the party’s ideological control shrouded by Chinese nationalism and the Americanism that would nurture any speech aiming at expressing one’s critical view in public.

The NBA case shows the kernel risk of thrusting oneself into the Chinese market: China has learned to weaponize its market. Thus, a Sino-US trade deal, even if it may well be envisioned in the leadership’s goodwill to reach a truce, could be shredded due to incompatibility between the party’s ideological control shrouded by Chinese nationalism and the Americanism that would nurture any speech aiming at expressing one’s critical view in public.

More profoundly, it is China’s fear that free speech constitutes a threat that engenders the butterfly effect of the Hong Kong protests at home, in its neighborhood, and among global trade partners. Pursuant to the philosophy of the party-state, free speech is preconditioned on zero impingement on the party rule and capitalism must be subservient to the party’s core interests. In the dictionary of Americanism – if one so couches the elements behind it – freedom of expression, albeit based on John Stuart Mill’s rationale of generating a “marketplace of ideas,” cannot tolerate any discount of its “market price.”

An ancient Chinese saying suggests that, for those whose paths will never cross, there is no point in taking counsel from each other. For understandable reasons, one may contend whether NBA’s free speech will wither in this broader context of trade war, and self-censorship will continue to spread among multinationals despite the deep roots and stronghold of free speech as shielded by the First Amendment. No matter which side might eventually hold advantage over the other, trade frictions between China and western countries, often mingled with cacophony regarding free speech, will constitute a normalized vision of international relations in the long run.

Western countries embracing the value of free speech may seek to counter China’s strategy of weaponizing its market, and a review of world history before World War II suggests that blindly following an appeasement policy generated disastrous consequences. However, weaponizing the global market, if not weaponizing the spirit of free speech, may be the least effective remedy. One trend can be expected: There will be no double-win in such free-speech–related trade frictions and only a greater chance of double-loss if systematic solutions are not found. As China’s nationalism boycotts Americanism, there is a long way to go if both countries really aim for a reliable deal on trade or anything beyond.

Ge Chen is assistant professor at Durham Law School. He is the author of Copyright and International Negotiations: An Engine of Free Expression in China? – a monograph published by Cambridge University Press in 2017. The book was featured in Harvard Law Review and presented at Yale Law School’s 2017 Freedom of Expression Scholars Conference under the auspices of the Abrams Travel Fellowship of the YLS Information Society Project. Dr. Chen has held academic and research positions in Oxford, Cambridge and Göttingen, and was a senior legal expert at the Mercator Institute for China Studies. He has advised the Chinese and European governments on a variety of legal projects under the Sino-EU-Dialogue of the State of Rule of Law.