Foreign Investment Isn’t Enough

Foreign Investment Isn't Enough

SALT LAKE CITY and ATLANTA, USA: Does foreign investment benefit or harm the economies of developing countries? Judging from recent events, the jury's still out. Negotiators at the Cancun WTO meeting last month failed to formulate a policy regulating foreign investment (See "Cancun Trade Meeting Should Leave Investment Issue Alone"). And on the ground in Bolivia, massive street protests decrying globalization forced the country's president to resign after 14 months in office.

Scientific studies over the past 30 years offer little guidance on the impact of foreign investment on development, with seemingly irrefutable "findings" on both sides of the debate. Neoliberals claim that capital, whether foreign or domestic, is a good thing. Foreign corporations may even provide additional benefits by bringing advanced technology to areas lacking strong research and development infrastructures.

Critics of the neoliberal position agree that foreign investment initially produces greater growth, but are less sanguine about its longer-term implications. They argue that reliance on foreign capital over extended periods prevents local industries from buying from and working with each other in order to produce goods in-country. Profits are repatriated to the investing country rather than re-invested locally. Income increasingly accrues to only the wealthiest individuals, who readily become the bedfellows of foreign investors and help construct economic, political and social policies that benefit outside interests rather than domestic needs. Critics conclude that these "unintended" consequences retard economic development even in countries with the most foreign capital.

But if the neoliberals' critics are correct, how do some countries with high levels of foreign investment, like Singapore, maintain robust economies while guarding against external influences on domestic economic policy? And why is it that other countries with less foreign investment - like Honduras - seem to be more influenced by foreign interests yet see little or no economic growth?

Our research on 39 developing countries suggests that it is the composition, or structure, of foreign investment that has the greatest impact on the economies of developing countries, rather than the total amount of foreign capital received. We refer to this aspect of foreign investment as foreign investment concentration, which is the proportion of a host country's foreign direct investment owned by the single largest investing country. A few examples may help to illustrate this new concept. In 1967, foreign investment concentration in the developing countries we studied ranged from a high of 98% in Honduras to a low of 34% in Singapore. This means that 98% of all direct foreign investment in Honduras was obtained from a single country - the United States, in this case - while in Singapore the single largest investing country (the United Kingdom) owned only 34% of foreign investment stocks. In these and many other countries, the level of investment concentration tend to be fairly stable over time, with the 1990 level for Honduras declining slightly (to 88%) and Singapore remaining around 35 percent.

It is high foreign investment concentration, not foreign investment itself, that hinders economic growth in countries like Honduras. High concentration levels allow foreign corporations - wittingly or not - to gain control over many economic, political, and social dynamics in a host country, thereby reducing the ability of the state and local elites to implement a national economic policy in their country's own long-term interests. Poor countries with a high concentration of a particular foreign corporate interest, such as Honduras, generate a pattern of dependency referred to as a "banana republic". States become weak and often corrupt, and dependence on export duties makes elites less willing to use demand-side stimuli to spur domestic economic growth.

Turning the state into a kind of company town, the investors and corporations from a single foreign country present the state with a vested constituency, unified to some degree by a common foreign nationality. The trade relationships that emerge in these instances tend to be unbalanced, with the host country having far fewer (enforced) regulations on land ownership, capital movements, employee welfare, or environmental degradation. Moreover, the investing country's government is more likely to use its influence to protect its business interests, whether by supporting regimes sympathetic to its interests or through direct military intervention (e.g. gunboat diplomacy). Armed intervention, instability, and conflict can disrupt a developing country's growth and scare off further investment.

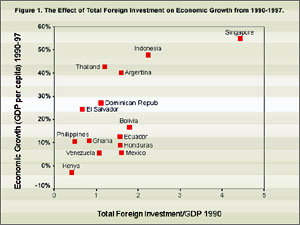

Clearly, the belief that more foreign investment means higher overall growth rates simply does not hold up to scrutiny, as an examination of the 1990-1997 period shows (see Figure 1). While in Singapore a high level of foreign investment was accompanied by rapid economic growth, other countries with relatively high amounts of foreign investment, such as Bolivia, Mexico and Malawi, grew slower than countries with less foreign capital. Kenya, with the lowest level of foreign investment, had a stagnant economy, yet other countries with low levels of foreign investment, such as the Philippines, El Salvador, and the Dominican Republic, had much stronger economic growth over this period. So what patterns are evident?

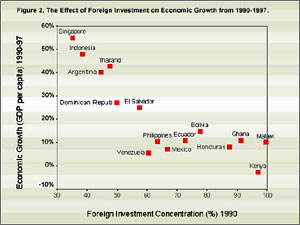

Again, if we focus on levels of foreign investment concentration rather than total foreign investment, a consistent pattern emerges: the higher the level of foreign investment concentration within a country, the lower its rate of economic growth (see Figure 2). For example, from 1990 to 1997 Singapore, Thailand, Argentina and the Dominican Republic - countries with the lowest level of foreign investment concentration - had the highest rates of economic growth. Kenya, Honduras, Malawi, Ghana, and Bolivia - countries with very high levels of foreign investment concentration - had the slowest per capita growth rates.

These findings suggest that the current debate on the benefits and drawbacks of foreign investment obscures the real issues. We need to focus instead on the structure of foreign investment. The question should be: under what conditions will foreign investment have positive and/or negative impacts on the economies of less developed countries? We have identified one such dimension - foreign investment concentration - which clearly retards economic growth in developing countries by weakening the autonomy of the state.

Certainly, foreign investment concentration is not the only factor that determines the effect of foreign investment on economic growth. Other "structural" aspects of foreign investment may have significant impacts on development as well. One such aspect may be where the foreign capital comes from - the "country of investment origin". Our tentative analyses suggest that developing countries that obtain most of their foreign capital from the United States tend to fare better than those countries with a majority of investment capital from other nations. A second determinant of growth centers on the sectors into which foreign investment is directed. Historically, most foreign capital has been invested in the manufacturing sector. Recently, however, foreign investment has increasingly been directed towards the service sector (i.e. financial, legal, advertising). Investments in these areas have a very different impact on local economies in terms of employment, raw material consumption, etc., and may not affect the host economy in the same manner as manufacturing investments. Finally, other types of foreign investment, such as portfolio investment, clearly have a significant impact on development.

The policy implications of our findings are significant. To promote growth, developing nations need to focus on attracting foreign investment from a variety of different countries. This diversification of investors will give host countries the autonomy - and leverage - necessary to develop and implement economic policies that will benefit the host country, as well as their foreign partners.

Jeffrey Kentor is Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Utah.

Terry Boswell is Professor of Sociology at Emory University. A longer version of this article appeared as “Foreign Capital Dependence and Development: A New Direction”, in the American Sociological Review (Vol. 68, April 2003).