Freeing India’s Textile Industry

Freeing India's Textile Industry

India's apparel-export industry is facing a moment of truth. The removal of world trade quota restrictions in January 2005 could bring a huge increase in India's annual exports and make it the big winner in the global market, after China. This breakthrough will occur, however, only if the government accelerates the pace of reform and local manufacturers adopt measures to improve their competitiveness, a study shows.1

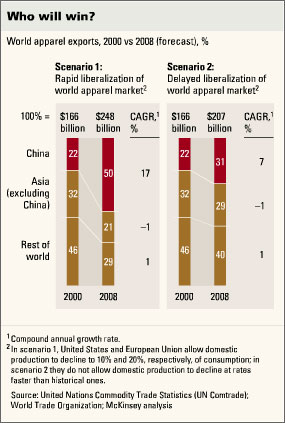

Productivity, labor costs, and quality, at least for higher-end goods, will determine which countries win or lose once the Arrangement on Textiles and Clothing (ATC) quota restrictions on apparel exports expire. China is likely to capture almost all of the resulting growth in global exports. Regardless of whether the United States and the European Union allow brand owners and retailers to buy freely or impose transitional safeguard mechanisms and increase duties, Asian countries that want to increase exports will have to take market share from one another and from countries outside Asia (exhibit).

India's garment industry has many advantages in this fight for market share: competitive labor costs, abundant raw materials (India is the world's third-largest producer of raw cotton), local textile production, and skilled designers. But the exporters' productivity is only 35 percent of US levels—compared with the 55 percent achieved by Chinese exporters—and the overall productivity of the Indian apparel industry, including tailors and domestic manufacturers, is just 16 percent of the US industry's productivity. With full-blown reforms, we estimate that Indian exports could increase by 15 to 18 percent annually—much higher than the historical growth rate of 6 percent. This expansion would enable India to win 5 percent of the global apparel-exports market by 2008 and to capture $25 billion to $30 billion by 2013. With only minor reforms, we expect annual growth of 8 percent at best.

Over the past five years, the Indian government has removed many of the barriers hindering the sector's growth. But to fulfill the potential of the country's apparel-export industry, the government needs to eliminate the remaining restrictions that perpetuate the lack of scale and poor operational and organizational performance of local manufacturers and that discourage investment, particularly foreign direct investment.2

Regulations still protect small-scale producers in a number of ways. While the production of ready-made garments is no longer reserved for small-scale manufacturers, a few product markets, such as hosiery, still are. In addition, Indian manufacturers often choose to set up several small plants, instead of a single big one, to take advantage of labor laws and a complex and inefficient tax regime that tends to favor small factories. As a result, Indian clothing plants typically have, on average, 10 to 20 percent of the machines that Chinese plants have.

Duties of around 25 percent on fabric imports limit the ability of Indian manufacturers to produce apparel made from a wide range of fabrics, thus making these companies less competitive in the global market. Moreover, tailors with low productivity who make custom garments for domestic consumers are a huge part of the sector—constituting 70 percent of its employment. To encourage Indian manufacturers to build scale, the government should relax labor laws, remove all remaining set-asides for small-scale players, and further reduce import duties on apparel, textiles, and machinery to the 10 percent level—the current standard in the majority of Asian countries.

India must reform its local markets in order to attract foreign direct investment, which has spurred spectacular growth in China's apparel-export industry. Restrictions on hiring and firing, including a law compelling companies with more than 100 workers to obtain government approval before reducing their workforce, should be removed. All indirect taxes on manufactured goods, such as excise and central and state sales taxes, should be replaced by a single nationwide value-added tax. And the total taxes on manufactured goods should be reduced from 25 to 30 percent of the wholesale price to 15 percent, the current level in China.

Other desirable government-led reforms that would help attract foreign investment and intensify competition include improving India's infrastructure (such as port capacity) and creating manufacturing clusters (so-called apparel parks). Eliminating barriers to competition forces manufacturers to improve their organizations—Indian apparel companies suffer from a much higher rate of absenteeism and more shipping delays than the average Asian exporter, for example—and to invest in technology to speed production and gain scale.

Since retailers and brand owners try to diversify their import channels, they are likely to source half of their apparel from countries other than China. India is well positioned to become the primary alternative—if it undertakes reforms quickly to make the apparel-export sector more competitive.

Click here for the original article on The McKinsey Quarterly's website.

Asutosh Padhi is a principal in McKinsey’s Delhi office, Geert Pauwels is a consultant in the Antwerp office, and Charlie Taylor is a principal in the Jakarta office.