The Future of Migration - Part One

The Future of Migration - Part One

CAMBRIDGE, USA: The late nineteenth and early twentieth century is well known as an era of massive migrations. Europeans settled in the USA, Canada, Australia, as well as Argentina and Brazil. Standing on the cusp of the 21st century, it is clear that another wave of mass migration is poised to break down the barricades protecting the world's rich and developed countries. There are five irresistible forces in the international system that - if left unaddressed - will soon lead to greater labor mobility and migration across national boundaries.

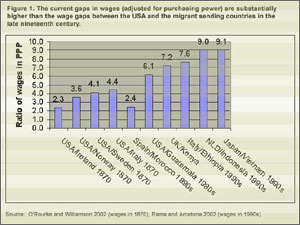

During modern times, the greatest gaps in wealth and living standards have shifted from differences between people within a country to differences between people around the globe. Inequalities in wages and standards of living have become larger than ever before in history - far greater than the inequalities that prompted so many to leave Europe during the migration age (see Figure 1). Studies estimate that in the 19th century only ten percent of income disparities could be attributed to the average income of the individual's respective country. In contrast, today over 60 percent of the world's wage and standard of living inequality is derived from differences in incomes between countries.

Such inequalities may not seem immediately relevant to the issue of migration. However, for individuals with similar qualifications - like education, labor market experience, and physical strength - nearly all income differences are associated with location. Migrating to richer countries allows people to boost their earnings without additional investments in health, education, or other personal characteristics. When migrants move, their wages are almost identical to workers in their adopted country, creating sometimes enormous incentives to re-locate.

The second major force that is increasing pressures for migration is the shift in the "optimal" population of various countries due to economic forces. A country's optimal population depends upon various economic, political, and geographic circumstances and poses the question, "how many people would live in a given spatial territory if there were perfect mobility and people could choose to move elsewhere?"

For example, say there is global labor mobility - how many of the 10 million people living in Niger would remain there? Would people choose to move to less densely populated areas? Likewise, if there were open borders between Nicaragua and the industrialized world, how many of Nicaragua's 5 million people would remain there after 10 years? The answers to both questions depend on the relative economic opportunities in each country.

If the optimal population of a country doesn't change, labor mobility is not really that important. Optimal populations may remain stable either because certain fundamentals don't change or other factors compensate for changes. Without changes in the geographic and economic interactions of a country, a region's attractiveness - and thus its optimal population - remains stable. Antarctica, for example, has been entirely unaffected by labor mobility because its attractiveness as a destination for human populations has remained the same across time.

The interaction between wages and labor mobility is therefore governed by a simple supply and demand dynamic: if labor supply is elastic and there are location-specific changes in labor demand, population shifts will result, though with little change in real wages. In contrast, if labor supply is inelastic and population movement is limited, there will be little change in population and large changes in wages. The evidence suggests there are in fact large geographic shifts in labor demand that lead to increased pressures for migration.

The third powerful force for the future of migration is divergent demographic futures resulting from different birth rates. Nearly all of Europe has witnessed immense changes in fertility behavior that has caused a massive contraction in national populations. The UN projects that the labor force of many European countries and Japan will not only cease to grow, but actually decline in coming years.

This contraction has several implications. The most obvious surrounds the financial viability of current pensions and social transfers. Indeed, the future "support ratio" of labor forces aged 25-64 to the "retirement aged" population seems daunting. Even under current conditions, the viability of these systems is questionable. But if support ratios fall to projected levels, either tax rates will need to skyrocket or benefits will have to be drastically cut.

In contrast, there are many countries whose populations are soaring. One of the fundamental principles of economics is that differences create incentives for exchange. These demographic differences are thus creating an incentive for better labor flow. However, in many countries population decline may prove too drastic to be alleviated by migration. Italy's labor force, for example, will need to be composed of 45 percent foreign born workers by 2050, if current population projections are correct.

The fourth powerful force behind increased migration is the increased interconnectedness of the world in terms of trade, capital flow, communications, and travel. The international system has created a mechanism for negotiating reductions in trade barriers. However, it is hard to make a compelling case for additional reductions to barriers to markets for goods while labor mobility is ignored. Goods markets are already deeply integrated. And while there is evidence of large "border" effects that inhibit trade, the price differences across countries are small relative to wage gaps. One could argue that this international system has created conditions in which labor mobility will become part of the agenda.

A general equilibrium model proposed last year by some economists estimates that allowing labor movements that would increase host country labor forces by only 3 percent would lead to world gains of $156 billion. Though this number represents less than one percent of world GDP, it is in fact three times larger than all official development assistance and far greater than the estimated gains from the all proposed remaining trade liberalization ($104 billion).

Finally, while there is enormous attention to technological changes that are reducing the pressures for labor movements (for example, all the media attention to "call centers" and "outsourcing" service workers) there are also growing demands for jobs that are not mobile. In the US Labor Department's prediction of the top ten occupations with the largest job growth, seven were location-specific (e.g. registered nurses, waiters and waitresses, retail salespersons).

The five forces I have outlined here are setting the world up for a massive migration unlike anything seen in the modern era. To meet the challenges of these pressures, governments, businesses, and communities must think carefully about their current policies and re-adjust them, where necessary, with a long-term view in mind.

References:

1. O'Rourke, Kevin H. and Jeffrey Williamson. 1999. "Globalization and History: The Evolution of a nineteenth century Atlantic economy." MIT Press.

2. Rama, Martin and Raquel Artecona. 2002. "A Database of Labor Market Indicators Across Countries."

Lant Pritchett is Lecturer in Public Policy at Harvard University’s John F. Kennedy School of Government. This article is adapted from a paper he presented at “The Future of Globalization: Explorations in Light of the Recent Turbulence,” a conference hosted by the Yale Center for the Study of Globalization on October 10, 2003. The complete paper will be presented as a chapter in a forthcoming edited volume of the conference proceedings.