The Global Abortion Bind

The Global Abortion Bind

have serious implications

NEW YORK: Many people find themselves caught in the abortion bind. On one hand, they support a woman’s right to choose to have a safe and legal induced abortion. On the other, they oppose sex-selective abortion, which in most instances discriminates against female fetuses and produces socially adverse gender imbalances. Reconciling these opposing reproductive-choice positions poses a serious dilemma of ethics and logic for individuals as well as for society at large.

Sex ratios at birth normally fall within a narrow band between 104 to 107 baby boys for every 100 baby girls. When sex ratios at birth of more than 107 were observed in the past, suspicions of female infanticide or abandonment emerged. More recently, however, unbalanced sex ratios suggest the use of sex-selective abortion, or termination of a pregnancy after determining that the fetus, almost always female, is not the desired sex.

The consequences of sex-selective abortion are evident in the two largest countries in the world, China and India, where preference for sons is strong. In these countries, which together contain nearly two out of every five people in the world today, the use of prenatal ultrasound scanning to abort female fetuses has led to skewed sex ratios at birth in favor of boys and a growing gender gap.

During the 1960s and 1970s the sex ratio at birth in China averaged around 106 boys for every 100 girls. But by the1990s, the ratio had reached 115 boys for 100 girls and is now believed to be close to 120. The 2000 census shows wide variations between China's provinces. Five provinces show more than 125 male births for every 100 females, with the most imbalanced sex ratios at birth in South China, in Hainan and Guangdong provinces with ratios of 136 and 130, respectively.

The practice of sex-selective abortion is also evident in India. Over the last five decades, the child sex ratio has increased from 102 boys for every 100 girls in the 1950s to 108 today. Higher ratios are observed in urban areas, 111, and in the wealthier Indian states of Punjab and Haryana, 126 and 122, respectively. Moreover, child sex ratios vary considerably among the major religious groups in India, with Sikhs having a high of 127 boys for 100 girls and Christians a low of 104.

Sex-selection abortion has become so prevalent in India, General Electric requests that any Indian company purchasing an ultrasound machines sign a waiver promising not to use it for determining gender followed by abortion.

In addition, sex ratios at birth tend to increase with higher order parities. In a recent household survey in India, for example, when the first birth was a girl, the sex ratio for the second birth increased to 132 baby boys for 100 baby girls. When the first two births were girls, the sex ratio increased further to 139. Sex ratios at birth were found to be higher among educated couples, better able to access ultrasounds and sex-selective abortions.

China and India have legislation prohibiting sex-selective abortion and its promotion, and authorities have vowed to take tough measures to control fetus gender testing and sex-selective abortions. In both countries, for example, it’s illegal for clinicians to reveal fetus’s sex during pregnancy using ultrasound scans. Moreover, China has pending legislation to jail anyone helping prospective parents learn the fetus’s sex. Recently in India, Prime Minister Manmohan Singh spoke out against female feticide, labeling it an uncivilized and reprehensible practice.

Nevertheless, with Chinese policy limiting couples to one child, which is being relaxed in the wake of large-scale death of schoolchildren in the May earthquake, and couples in India increasingly having fewer children, authorities face challenges enforcing prohibitions against sex-selective abortion because of widespread cultural beliefs that the family is incomplete without a son. Couples expect sons to continue the family name and bloodline, earn money, look after the family, perform ritual functions and care for parents in old age.

In contrast, daughters are often considered liabilities, costly to marry off and part of their husbands’ households. Raising a daughter, according to one Punjabi proverb, is like watering the neighbor’s garden. While many couples may acknowledge that both genders are needed for societal wellbeing, they prefer that neighbors have daughters.

Enforcement of laws and regulations against sex-selective abortion is further complicated by the fact that clinicians need only to wink or cringe to indicate gender. Banning the practice has simply pushed it underground.

The growing gender imbalances among these mammoth populations become particularly worrisome when children reach adulthood. Due to the relative shortages of eligible women, some young men find it more difficult to form heterosexual romantic relationships and find wives.

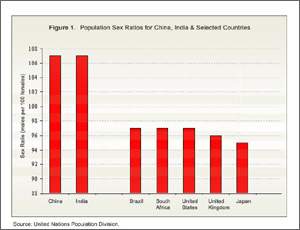

China and India both have significantly more males than females among their populations, a sharp contrast to demographics in most developed countries and many developing countries where females outnumber men (Figure 1). By 2020, it’s estimated that the number of young “surplus males” unable to find brides could be more than 35 million in China and 25 million in India.

As in all societies, raising a family is a fundamental tradition in Chinese and Indian cultures. Given such strong familial emphasis, the acute gender imbalances are unlikely to lead bachelors to celibate lives as priests, monks or sadhus.

More likely, sex imbalances will push many men to look for brides in younger age groups, allowing the re-emergence of customs like child brides or marriage promises. Men unable to marry locally may need to import brides from distant regions. Also, some suggest that large numbers of surplus bachelors are likely to generate crime and civil disorder, such as the growth of urban gangs, increased trafficking of women, prostitution and bride kidnapping. The trends could even lead to the build-up of large militias to provide a safety valve for the frustrations of numerous bachelors.

Increasing evidence suggests that the practice of sex-selective abortions is occurring among Chinese and Indian immigrant communities living abroad. In the US, for example, figures from the 2000 census indicate US-born children of Chinese, Indian and Korean parents tended to be male. Countries that permit induced abortion, such as Canada, Germany and the UK, have outlawed sex selection for social reasons, and member states of the United Nations have collectively adopted recommendations urging governments to take the measures to prevent prenatal sex selection.

Medical technology has added a new dimension to the induced abortion debate: gender bias.

Allowing parental choice on the sex of their offspring represents the first major step toward exercising control not over whether, when and how many children to have, but over what kind of children are acceptable. Permitting couples to choose the sex of their children is viewed as a slippery slope by some ethicists, leading to “designer babies” selected on the basis of characteristics such as appearance, height or intelligence.

Others, however, while acknowledging that sex-selective abortion is a morally reprehensible practice, stress a woman’s right to choose her reproductive outcomes as paramount. Many pro-choice and feminist groups are convinced that outlawing sex- selective abortion will undermine the reproductive rights of women. When they choose to address this highly sensitive issue, they advocate changing the son-preference mindset of the public through education campaigns that stress the value of daughters. Such an approach alone may prove to be a Herculean task in countries such as China and India. Economic development that provides equal education and employment opportunities for men and women is far more likely to be effective in eliminating son-preference in these societies.

These weighty matters no doubt will become more complicated with medical advances, such as the widespread use of home gender and DNA kits, raising further difficult issues surrounding induced abortion and putting more people in the abortion bind.

Joseph Chamie is research director at the Center for Migration Studies and former director of the United Nations Population Division.