A Global Economy in Danger

A Global Economy in Danger

SINGAPORE: Deliberations on leaving a secure Afghanistan after NATO withdraws- as NATO is doing in Chicago today – are essential. But the world is facing an even more urgent crisis that calls for immediate, coordinated action by the Group of 20.

A confluence of dangerous trends threatens the global economy. Virtually all major sources of demand in the world economy seem to be seizing up at the same time – the eurozone is facing multiple stresses, the Chinese economy is slowing at a worrying pace, Japan’s recovery from its triple disasters is hobbled by a power shortage, and recovery in the US economy appears to be losing momentum. Since these major economies are interconnected in so many ways, we should expect these risks to reinforce one another and produce an outcome far worse than what might be expected if examined individually – hence the need for swift, coordinated policy responses at the global level.

The major drivers of the global economy are at risk. Amid much uncertainty, some projections can be made.

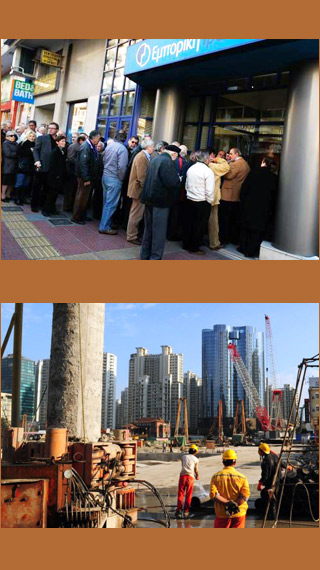

First, the eurozone will suffer a deeper recession than forecast, coupled with substantial financial disturbances and huge political uncertainty.

With Greece facing the prospect of a chaotic exit from the euro, the eurozone’s downward spiral is moving faster. The combination of the deleveraging after the financial crisis and fiscal austerity to deal with the sovereign debt crisis is producing more than just a recession. It’s creating a political backlash that makes it increasingly difficult for governments to adhere to the bailout packages which had temporarily brought relief from the crisis. But since the bailout packages are a delicate assemblage of fragile compromises to accommodate sharply divided views on policies, failure to honor one part of the package could upset the entire assemblage. With Greece unlikely to have a government that will deliver on bailout conditions, a Greek default and exit from the euro are now dangerously possible.

Concern emerges over other financially stressed economies in the region. Because Spain is already wilting under the pressure of recapitalizing its troubled banks while still restraining public deficits and debt, attention has shifted from worrying about relatively small countries like Greece or Ireland to the bigger countries which cannot so easily be bailed out. With France now led by an untested new president who demands a renegotiation of critical parts of the eurozone bailouts and with Italy’s technocratic government losing support, the crisis could well spread to larger economies – the regional election setback suffered by Angela Merkel’s party points to the problem – and lead to the more extreme scenarios of a eurozone breakup that appeared unlikely just weeks ago.

Second, China’s economy – the largest source of growth in global demand – is slowing sharply. April’s economic readings shocked markets – industrial production, fixed asset investment, retail sales and exports lost momentum precipitously. Domestic and external demand is weakening far more rapidly than expected. Financial markets are still hoping that resolute monetary and fiscal policy responses will be enough to turn the economy around. There are powerful reasons why markets will be disappointed. Chinese policymakers’ room for maneuver is limited – unlike in 2008, the economy is challenged not just by a slowdown, but also by inflationary pressures and speculative behavior, especially in real estate that had created imbalances in the economy and triggered public anger. Chinese policymakers know that premature easing of policies could rekindle these risks. The massive 4 trillion yuan policy response of 2008 simply won’t happen again.

Third, the US economic recovery will remain modest at best and therefore highly vulnerable to external shocks such as renewed financial distress in global markets or weakness in major export markets such as Europe and China. The US economy was starting to put into place the foundations for a sustainable recovery – easing credit conditions, rising business and consumer confidence, the housing market finding a bottom and easing unemployment. However, recent data cast doubts on the recovery’s durability in these areas. Moreover, with job growth still anaemic and household incomes barely growing in real terms, consumer demand – 70 percent of the economy - has been largely sustained by a fall in the savings rate which cannot continue. In this context, the US economy is not in a condition to absorb the potential shocks from its major trading partners or deal with the painful fiscal adjustments which cannot be avoided for long. The US economy is not going to fall into another recession, but neither is it going to enjoy more than modest growth.

Fourth, the Japanese recovery is at risk. The loss of nuclear-generated electrical power is likely to weaken Japan’s recovery from the triple disasters of early 2011. Total power supplied fell by 7.6 percent over the course of the fiscal year that just ended in March as a result of the shutdown of its nuclear plants. The shutdown will particularly be severe in the Kansai region where several of Japan’s production centers such as Osaka, Kyoto and Kobe are located. In addition, uncertainty looms over government plans to raise consumption taxes in order to address the huge fiscal debt.

Fifth, these unfavorable developments will not operate in isolation. Instead, they will reinforce one another and produce a sharper than expected deceleration in global demand. With all the major engines of global growth weakening simultaneously, the risks are that each of these major economies pulls down its major trading partners. Unlike Asia’s experience during its 1997-98 crisis, today’s distressed economies cannot rely on still-strong global demand to power a recovery. They are the global economy – together representing near 70 percent of the global GDP of $63 trillion in 2010. The US, Europe and China are so large, so interconnected through trade and investment flows, that negatives in one country reinforce negatives in another.

Coordinated global policy actions are needed to break the downward momentum. Individual countries are constrained by huge debt levels, and worries about inflation or currency risks from embarking alone on the substantial policy responses that are n eeded. The G20 needs to be activated and confidence restored through a series of measures:

First, there must be a commitment to simultaneous fiscal stimulus – with fiscally stronger economies such as Germany, China and the oil exporters doing the heavy lifting while the fiscally challenged economies are allowed to phase in deficit reduction more gradually.

Second, the world must strengthen defenses against financial panics. The firewalls – such as the International Monetary Fund and the eurozone’s stabilization funds – should be expanded substantially enough to convince financial markets that they can deal even with the larger eurozone economies that are at risk. There should be an explicit commitment given to recapitalize banking sectors in Europe which are increasingly in distress.

Third, emerging economies should commit to a simultaneous easing of monetary policies.

Fourth, the oil exporters need to make a firm commitment to sustain as much an increase in oil production as possible so that oil prices fall by enough to boost global demand. A fall in oil prices would also help restrain inflationary pressures, making it easier to adopt the expansionary policies mentioned above.

In short, the global economy is at risk of a downward spiral, and only powerful globally coordinated policy actions can prevent a major crisis.