Global Energy Transport Security

Global Energy Transport Security

Energy worries: Attacks on oil tankers and Iran’s detention of the British-flagged Stena Impero in the Strait of Hormuz, as seen in undated photo, raise concerns for the liquefied natural gas industry; about 25 percent of the world’s LNG exports pass through Hormuz, with Qatargas a leading global producer

PROVIDENCE, RHODE ISLAND: A series of attacks and detentions for oil cargo ships this year have made the Strait of Hormuz a geopolitical hotspot once again, harkening back 35 years to the so-called “tanker wars,” part of the Iran-Iraq War. And while Hormuz’s role as the world’s primary most important oil transit route has not changed, much else about the energy security landscape has – especially growth in liquefied natural gas markets. The concerns around disruptions to oil markets are now salient for natural gas markets as well.

In today’s numbers, an average of more than 20 million barrels pass through the strait daily, about 20 percent of the world’s oil consumption, with 75 percent destined for Asia. And while wars for direct oil conquest are relatively rare, oil is frequently involved in wars in other ways. Research published by the Belfer Center at Harvard University points to complex connections between oil and geopolitical conflict, including resource wars, insulation of aggressive leaders and financing of insurgencies. The report on “Oil, Conflict, and U.S. National Interests” notes: “between one-quarter and one-half of interstate wars since 1973 have been linked to oil.”

The Trump administration’s April decision to re-impose sanctions against Iran’s oil exports, coupled with the Iranian government’s bellicose rhetorical response looms large as the reason for the recent flare-up in the Strait of Hormuz. The UK Navy seized an Iranian tanker off the coast of Gibraltar in July, and subsequently a British-flagged ship was detained by the Iranian Revolutionary Guard in the Strait of Hormuz. After six weeks, Gibraltar allowed the Iranian tanker to leave, despite pressure from the United States to transfer Grace 1, renamed Adrian Darya-1, to its custody. Britain hopes for the release of its tanker, the Stena Impero.

The US military presence in the Persian Gulf has a long history. Former US President James Carter laid out what became known as the Carter Doctrine in the 1980 State of the Union address, helping define the long-term US approach to energy security and foreign policy: “An attempt by any outside force to gain control of the Persian Gulf region will be regarded as an assault on the vital interests of the United States of America, and such an assault will be repelled by any means necessary, including military force.” The US Navy’s 5th Fleet, under CENTCOM, has since been a staple in waters of the Persian Gulf. It was recently joined by two Royal Navy ships.

During the Iran-Iraq war, 1980 to 1988, both sides tried to sink the other’s oil tankers – with little success. Massive tankers are hard to sink. Crude oil, while flammable and a pollutant, is neither volatile nor likely to explode. The result, as political scientist Caitlin Talmadge’s research shows, is that the Strait of Hormuz is not easily closed – or at least, not until recently.

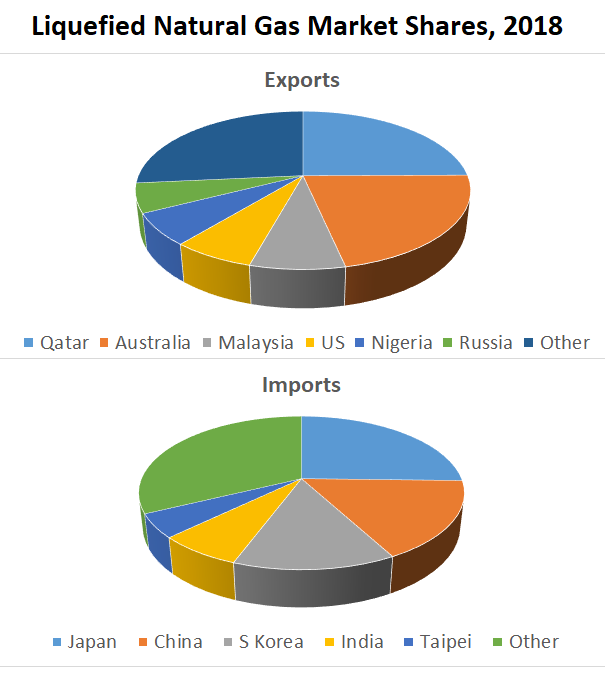

That has changed. About 70 percent of Iran’s exports in 2017 were crude petroleum. For Qatar though, unlike during the 1980s, liquefied natural gas represents about 60 percent of its exports, all of which sails through the Strait of Hormuz onboard tankers. The two main exporters of LNG through the Strait are Qatar, historically the largest exporter of the product in the world, and the United Arab Emirates. And there are also regional importers, including Kuwait, notes the 2019 International Gas Union report.

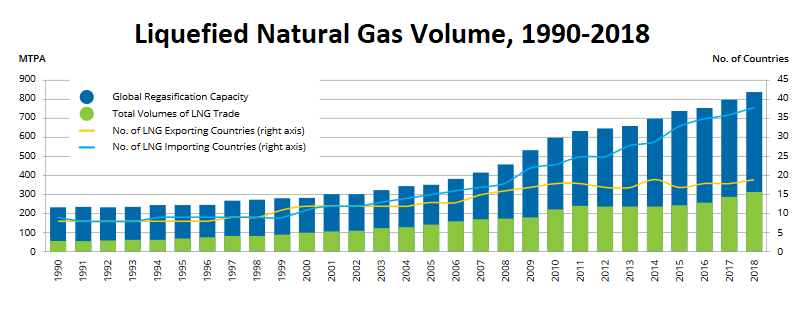

LNG is a fuel on the rise, with demand up nearly 5 percent in 2018 – equating to about half of all global energy demand growth that year. And analysts, including those from the International Energy Agency, anticipate future demand to be driven by the Asia Pacific region, especially China. Uncertainties around transit go well beyond the Strait of Hormuz. Global gas security is a complex and emerging area of analysis.

LNG trade is dramatically altering the energy map. In 2018, for the fifth straight year trade in LNG grew, setting a new record of over 300 million tons. Of that, 83 million tons of LNG exports went through the strait. This rapid growth makes it more difficult to predict implications from conflict. The US Energy Information Administration now includes some data on LNG flows through Hormuz, with its oil analysis.

The United States now exports crude oil and is the largest producer of oil in the world. The United States also exports LNG to more than 30 countries, thus redrawing energy trade patterns, markets and international relations. The United States is expected to surpass Australia and Qatar to become the world’s largest LNG exporter before 2025, reports the International Energy Agency.

LNG is volatile, and those tankers may be more vulnerable to attack than oil tankers. Major attacks on LNG tankers would not only disrupt natural gas markets worldwide, but could snarl the flow of oil through the Strait of Hormuz. As early as 2004, the US Department of Energy began commissioning studies about LNG transport safety and issues of intentional breach and cascading failures. Two main concerns: “LNG vessel structural steels being extremely brittle at LNG temperatures (-161oC), and LNG fires generating very high temperatures (exceeding 1000oC) that will lower the strength of structural steels.”

So far, there have been few attacks on LNG tankers. In 1984, during the Iran-Iraq War, missiles hit a tanker carrying butane and propane, starting a fire. The tanker survived the attack. In 2018, pirates tried to attack a LNG tanker off the coast of Nigeria without success. Yet the rising scale of LNG trade could make these tankers a tempting target.

The Strait of Malacca, long the second major oil checkpoint, is also a LNG route from the Persian Gulf and Africa to Asia. At its widest, the strait is less than two miles, creating a vulnerable area for piracy or other attacks.

Once highly regional markets for natural gas in Asia, Europe and North America are also being impacted by the new scale, changing contract types and landscape for the LNG trade. And while a type of global market will likely emerge, the regional nature of the markets means that disruptions in the Strait of Hormuz might impose more significant impact on prices and importers than in the case of oil markets.

This summer, the United States began deploying troops and Patriot missiles in Saudi Arabia, possibly in response to oil infrastructure vulnerabilities, though international security experts question if such a missile attack from Iran would work. More ominously, other observers wonder if the countries prepare for war.

We caution that oil and energy are rarely a cause of war on their own, and geopolitical relationships add complications. Policymakers should be aware of Iran’s history of petro-aggression, use of the “oil weapon” by the United States, and links between oil and war.

The new reliance on natural gas is making the calculus of conflict more complex.

Jeff Colgan is the Richard Holbrooke Associate Professor of Political Science at Brown University. He is author of Petro-Aggression: When Oil Causes War (Cambridge University Press, 2013). Follow him @JeffDColgan

Morgan Bazilian is Professor of Public Policy and Director of the Payne Institute at the Colorado School of Mines. He is author of Analytical Methods for Energy Diversity and Security (Elsevier Science). Follow him @mbazilian