Globalization and the Middle East: Part Two

Globalization and the Middle East: Part Two

Islamic fundamentalism is often understood as a straight return into a distant past. Its ideology of a revival of the Prophet Muhammad's political message is seen aimed at countering the impetus of modernization in many countries of the Middle East. Equally, it has often been said that Muslim fundamentalism has turned the Middle East into a region which is most successfully - and most tragically - opposed to the effects of globalization. The world of 2003 has become a much smaller place than the one of the Prophet Muhammed, and Islamic law, its critics say, is ill-suited to serve a globalized citizenry.

But if globalization is taken to mean increased inter-dependence and interaction in a world reduced in size by the revolutions in transportation and communication, then this could be not further from the truth. Islamic fundamentalism has been, in fact, strengthened by globalization. In the Middle East it is one of its driving forces. Muslim fundamentalist movements are benefiting from an increase in the flow of information, speed of communication, and mobility more than any other political movements in the region. Their vision of a globalized society, however, is quite different from the pleasure-seeking, profit-driven western lifestyle that is being promoted by the globalization that we focus upon most. The Islamists' ideal of a globalized society is the network-connection of all "real" Muslims and their organizations in order to promote their definition of Islam.and what they view as "Islamic."

Globalization should not be equated with the Westernization of the world. A close look into the Islamic world reveals that it does indeed actively participate in the various processes of globalization, probably even more than many other regions of the world, and that Islamist movements are one of globalization's motors. The Islamic world itself has become something like an "Islamic village" mainly due to the activities of the Islamist groups. The technological advances of the 20th century led to a kind of globalization in the Islamic world that has yet to be recognized in its full scope.

For the West, the most visible expression of globalization in the Islamic world were the attacks of September 11. The terrorist attacks of that day are the result of what might be called the globalization of several civil wars and political conflicts between Islamists, military governments, like Syria and Algeria, or monarchical governments like the kingdoms of the Arabia Peninsula, led by Saudi Arabia. The attacks were the terrible consequence of a strategic decision on the part of the most radical Islamist movements stemming from their defeat in many Muslim countries. The developments of the national jihad in Muslim countries like, for instance, Algeria and Egypt, were remarkably similar. In the years between 1992 and 1997, both nations saw extremely bloody battles in a war between militant Islamists who wanted to take over the governments of these countries. The increasingly violent actions of the Islamists in these two countries turned the masses against them and alienated their own supporters. Subsequently, both the leadership as well as many of the foot soldiers of the militant Islamist movements either made their peace with the authorities or went into exile. Some became part of the Muslim diaspora in Europe where they would continue the work as a jihad vanguard despite their disconnection from the political issues that carried their struggle in their home countries. Others went to Afghanistan, where they had enjoyed a safe haven since the 1992 overthrow of the communist regime. Here, they would meet those who earlier had left the Arab world in order to fight in the Afghan jihad against Soviet occupation. The rest of the story is well known. The different strains of defeated Islamist movements were picked up and connected under the leadership of the Saudi renegade Osama bin Laden and the Egyptian jihad leader Ayman al-Zawahiri. Their organization, al-Qaeda, is the first truly global terrorist network that would use e-mail, internet, frequent flyer miles, wire transfers, and tourist, student, and refugee visas in order to organize a globalized jihad.

While globalization of the several armed struggles in the Muslim Middle East became frighteningly effective until the crackdown following September 2001, the militant Islamists claimed that globalization was also the cause of the new jihad. In their analysis of the defeat within their home countries it was not only their incapacity to keep the connection with their mass base that led to their failure. The Islamist groups blamed the West's and particularly America's active support of their enemy governments. In the case of Egypt, for instance, they pointed to the roughly $5 billion that the U.S. pays annually to the government in Cairo. When the military government in Algeria canceled its first democratic ballot scheduled in 1992, France, which took the leading role among the Western countries in this case, actively supported the military coup. In fact, the military government in Algiers became so attentive to Western support that at one time, the Islamists claimed, the authorities murdered a group of Italian sailors on board their ship in an Algerian harbor and staged the event as if it has been committed by the Islamists. This was all done, it was claimed, in order to ensure continuing Western support in the conflict.

In an article in the Times Literary Supplement in March 2002, the commentator Navid Kermani argued that the attacks of September 11 could hardly be inspired by Islamic ideals but were rather nihilistic acts of destruction devoid of any political message. For the followers of the globalist jihad there certainly was a message. The message al-Qaeda conveyed to its sympathizers was that of the effectiveness of a globalized jihad. The globalized jihad had begun in 1996 with al-Qaeda's declaration of war against America and its citizens, renewed in 1998 and in several of its videos since. The new jihad is being portrayed as the response to the increasing influence of Western nations on countries of strategic importance for the West like Egypt or Algeria that would become unable to decide their own future. The chosen targets of September 11 - Wall Street, White House, and the Pentagon - represent for al-Qaeda not simply the symbols of American economic, political, and military might. They would also be the places where the people whose decisions affect everybody's life in countries like Egypt and Algeria go to do their work. In the eyes of al-Qaeda, the victims of September 11 were no innocents and not collateral casualties. They would be the ones who in the White House support the Islamists' enemies in the governments of the Middle East. They would also be the ones who in the Pentagon decide the deployment of troops in the region, or on Wall Street who devalue every single working hour in a foreign country if they choose to trade its currency with a point less than before.

But does it make sense that a globalized organization fights globalization? This statement becomes less contradictory once we understand that globalization may take more than one direction. We mostly think of globalization as a process where the ideas of Western modernity, of economic development in a capitalist model, and of Western cultural production are brought to other parts of the world. We fail to see, however, that other regions may seek their own kind of globalization. Although the Muslim community has seen a remarkable spread and is now present in countries where it was largely unknown 40 years ago, it is much more uniform than it was back then. Traditionally each Muslim nation, each country, and sometimes even each region had its own way to practice Islam. Yemenite Islam was quite different from Moroccan Islam, for instance. While these differences still exist, faster and more effective means of communication lead to the fact that books, websites, or TV programs written and produced in Morocco may today be found in Yemeni homes and the Yemeni marketplace. The widespread use of the Arab language in the Muslim world, as well as the strong sense of unity and uniformity that is part of the traditional Islamic teaching, gives it a headstart before other religious communities. With the advent of satellite TV like Qatar-based al-Jazeera, local newspapers and TV stations, often controlled by the state, lost their monopoly on information. TV pictures broadcast from places like Jenin or Peshawar today often determine the subjects of a national debate that once seldom touched upon these faraway issues.

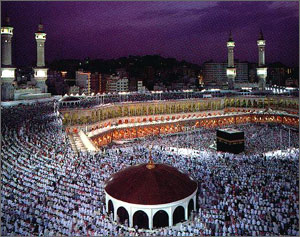

Advanced means of transportation led to the increase of annual pilgrims performing the traditional hajj to Mecca from 79,000 in 1929 to 2 million by the 1980s. In fact, the most important forces pushing globalization in the Islamic world are the petrodollars of the oil-rich states on the Arab peninsular. The petrodollar earnings of the migrating workforce, for instance, created an Islamic banking system that avoids fixed interest rates and effectively connects most of the countries of the Middle East. The petrodollars spread by the Saudi government also led to the construction of over 1,500 new mosques all over the Muslim world. The flow of this money causes the same reactions that globalization has in the West. In Morocco, for instance, where for centuries minarets of mosques have always been built in a square shape, one now sees more and more round minarets inspired by those in the rich Islamic east. Many Moroccans feel the same way about these round minarets as Italians feel about a McDonald's restaurant in their old historic cities.

The most important effect of the globalization of the Islamic world was, however, the creation of a standard understanding for what the words "Islam" and "Islamic" mean. Prior to the changes that came with faster information and higher mobility, the norms of what "Islamic" was in a society and what was not were decided on a local, regional, or national level. Each country had the opportunity to find its own interpretation of the Islamic message. This, however, has become increasingly difficult once the more conservative groups within the Islamist movements found the support of the Saudi government's resources. The affinity of Wahhabism, the local branch of Islam predominant in Saudi Arabia, with conservative Islamic fundamentalism of widely read authors' like Sayyid Qutb or Mawlana Mawdudi, led to a joining of forces. As a result, the norms of what is regarded as "Islamic" in the globalized world are less and less set by the local traditions of interpreting Islam, but increasingly by a joint version of the standards of Wahhabism and Islamic fundamentalism.

It would be a mistake, however, to regard the developments in the Islamic world as a counter-globalization against the one originated in the West. Instead of rejecting globalization, the Islamic world is finding its own way of globalization. The two processes use the same means and the same tools and are indeed inseparable. They go, however, into different directions. Muslim fundamentalist movements encourage the use of the internet among their followers, for instance, not in order to sell something by e-mail order, but rather to promote the creation of a network of like-minded people who share a common understanding of what "Islam" means and what it advocates. These different directions should probably not be just reduced to two - one pro-Western and one that is countering the West's impact. While Westernization is clearly the most dominant direction of globalization, one finds on a closer look that other processes of globalization are going on which take various directions. The lack of exchange that we currently have between these global networks, particularly between the networks of the West and the Muslim world, can only be overcome by greater and much more open communication and exchange. Globalization means both giving and taking. Here, it would call for more listening to the other in order to avoid that they continue to talk only to themselves.

Frank Griffel is Assistant Professor of Islamic Studies in the Department of Religious Studies at Yale University.