Globalization Forces a Health-Check of US Auto Industry

Globalization Forces a Health-Check of US Auto Industry

NEW HAVEN: Turmoil in the US auto industry continues to grab headlines, most recently with rumor of a merger between two giants, General Motors and Chrysler. Whether that comes to pass or not, the US automobile industry that once helped ensure the nation’s domination of world manufacturing has become exhibit A for the ill effects of globalization.

A closer look reveals how the industry’s declining profits and rising layoffs are a product of both global competition and failure of domestic reform. Nations cannot insulate domestic policies from globalization’s cost-cutting pressure, and the US must endure painful alignment with global trends in non-trade issues like health care.

Since the launch of the Model T by Henry Ford in the early 20th century, the US has been the world’s largest maker of cars. But no more. To reduce costs, the auto industry led all US sectors with job reductions in 2006 – more than 150,000 in all. The major firms will close more than 15 plants by 2010. Japan’s Toyota could bump General Motors from its perch as the world’s leading automaker this year.

Such woes stem from US resistance to two global trends: the drive toward fuel efficiency and universal health coverage. US fuel prices, among the lowest in the world, discouraged the design of smaller cars, and post-WWII prosperity discouraged Americans from embracing less costly national health care.

Toyota and other firms that offer fuel-efficient vehicles gain market share with every spike in the price of oil – starting with the OPEC embargo in 1973 and more recently with growing Asian demand. Imports now hold about 40 percent of the US market. Yet US firms would stall without global trade: GM has captured the top spot in the Chinese market, and US firms save money by using parts made in Asia.

By purchasing parts made overseas, US manufacturers avoid high labor costs at home. It also means laying off thousands of workers who produced those parts. One reason behind the high labor costs: The US stands alone among developed nations with its lack of a government-funded health program that reins in costs.

Of the top six auto-producing nations, only the US and China do not provide universal coverage. Since 1950, the US counted on businesses to provide health-insurance coverage to both workers and their families – no burden during post-war boom years.

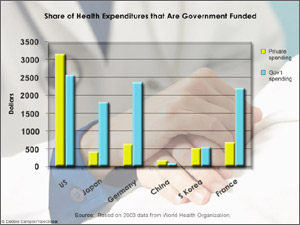

In contrast, Japan has required membership in national or employee insurance programs since 1961: Individuals pay about 20 percent of their medical costs up to a ceiling, after which full coverage is provided. Only China has a higher percentage of private expenditures than that of the US (see graph): About half of China’s urban workers are insured and pay up to 50 percent of costs; most rural workers are uninsured, paying for care with saved or borrowed funds. Or they go without.

In response to low wages overseas, US firms move jobs abroad and reduce health-care benefits at home.

Health care raises the price of each GM car by $1,500, complains CEO Rick Wagoner. That figure, bandied about by the media, is unsound for several reasons. The calculation overlooks government subsidies: Tax subsidies for employee-sponsored health-care coverage on active workers exceeded $200 billion in 2006, reports the US Internal Revenue Service.

GM’s own policy analysts divorce themselves from the figure because health-care costs per car vary, depending on which parts, from light bulbs to seat covers, are outsourced.

Besides, with every plant closure, health-care costs per car rise because US firms carry an extra burden of coverage for retired workers. GM covered health care for 1.1 million people in 2005, almost 70 percent of whom were retirees or workers’ family members.

To regain some competitive edge, the executives want autoworkers to accept cuts in health benefits or the Democratic majority in Congress to reduce health-care costs. Medical care has long served as a hot issue for Democrats, who express concern about the growing numbers of uninsured, now 15 percent of the US population.

A shrinking majority of Americans, now 59 percent, hold employer-provided coverage. Voters demand more health care, so the issue appears intractable. In 1994, President Bill Clinton couldn’t convince another Democratic-controlled Congress to consider a health-care reform package, proposed by a task force led by Hillary Clinton, then first lady, now senator for New York and a presidential candidate.

The government picks up the health-care tab for the poor and elderly. Yet, US health care is a powerful industry that generates profits and donates funds to politicians who propose expanded services rather than painful cuts. Between 1998 and 2005, the pharmaceutical and insurance industries ranked first and second in lobbying expenditures, according to the Center for Responsive Politics. Lobbies representing pharmaceutical and insurance industries, hospitals and health-care professionals combined spent more than $2 billion for the period.

Health-care and social-service workers now outnumber manufacturing employees, according to US Census data. Consequently, bringing US health spending in line with that of emerging manufacturing nations is difficult to achieve.

It’s not just the health of the auto industry that hinges on reducing health costs. A system that spends almost $2 trillion annually on health care is unsustainable as long as patients demand first-class treatment while expecting someone else – government or employers – to pay for it.

States have unveiled plans to tax businesses that do not offer health insurance and require citizens to purchase coverage, and the Bush administration proposes complex changes in the tax code. But the piecemeal approach only creates loopholes and leads to more deterioration in US competitiveness.

Americans can no longer afford indulging in more health-care spending per capita than other top nations that manufacture autos – Japan, Germany, China, South Korea and France.

The economics of US health care are not hopeless. A once-dominant manufacturing industry can be reinvigorated.

A government-funded system of basic care could increase US competitiveness by decreasing administrative and other costs and emphasizing prevention. Individuals and companies could purchase extra insurance for private care. Reform could guarantee basic care for all citizens. Incentives could limit an obsession with quick fixes, both in medical treatment and policies.

Government regulation could allow US auto-manufacturers to focus on product innovation rather than health care. Firms like Toyota and Tata of India scramble to design small cars for developing nations – costing as little as $2500. To keep up, US industry must adapt products to a limited supply of energy combined with increasing global demand.

US auto manufacturers want a national health-care plan, suggests Michael Stanton, president of the Association of International Automobile Manufacturers, with confidence.

Bruce Bradley, director of General Motors health-care strategy and policy, denies the existence of any silver bullet, yet notes that government is the largest purchaser of health care and, with industry, can “have an impact on the provider community.”

One way or the other, Americans must reduce health-care costs – or risk killing the industrial golden goose that has provided so much prosperity. Globalization, which delivers low inflation and low-priced consumer goods, requires US industry to invest in both health-care reform and innovative designs for a changing market. Or else, the US will lose any hope of a competitive edge in a borderless market.

Susan Froetschel is assistant editor for YaleGlobal Online.