The Hollowing-Out of Hollywood

The Hollowing-Out of Hollywood

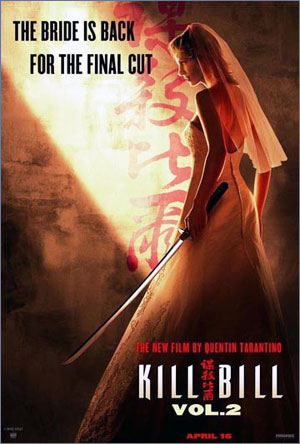

CAMBRIDGE, MASS.: Quentin Tarantino's "Kill Bill: Vol. 2" opened strong in US theaters this past weekend, taking in over $25 million at the box office. Last autumn, "Kill Bill: Vol.1" opened to similar financial and critical success. These films have generated a lot of media attention because of their "global" style: they appropriate stylistic elements from Hong Kong kung fu movies, Japanese samurai films, and Italian spaghetti Westerns, and wrap them all up in an exaggerated, comic-book sensibility. Yet the "Kill Bill" films are important not only for their global style, but also because their profitability rests upon a growing production trend - the offshoring of Hollywood filmmaking.

The "Kill Bill" films relied heavily on the labor of offshore workers and overseas locations. Yet outsourcing is nothing new to Hollywood. Previous generations of Hollywood films have sent animation, visual effects, and post-production work to companies overseas. There is a new sense of crisis among American film industry workers, however, over "runaway productions" - films and TV shows that for economic reasons are shot wholly or almost wholly outside the U.S.

While runaways typically employ Americans as producers, directors, and stars, most of the crew and some non-star actors are hired locally. Runaway productions have existed since the late 1940s, but their numbers increased during the 1990s. According to a 1999 study commissioned by the Directors Guild of America and the Screen Actors Guild, runaways have increased from 14 percent of total US film and television productions in 1990 to 27 percent in 1998. They have a total negative economic impact of over $10 billion a year. Today the practice has reached what the Los Angeles Times calls "epidemic" levels and involves many big-budget, high-profile pictures like the Academy-Award winning "Chicago". The DGA/SAG study calculates that over 125,000 jobs were lost to runaways in the 1990s. A more recent study by the Los Angeles Economic Development Corp. predicts that another 4,000 film jobs will likely disappear by 2005.

The studios' need to cut costs at the behest of their struggling parent conglomerates is driving work offshore. Canada has been Hollywood's foreign location of choice, hosting more than 80 percent of all runaways in the late 1990s. The Canadian government's program of tax rebates and incentives, combined with lower production costs and a favorable exchange rage, can reduce a film's budget by about 25 percent. But just as Mexico lost some formerly US-based factories to China, Canada is now facing increased competition from countries offering even lower wages and more generous tax breaks. Australia and the Czech Republic have become popular destinations over the past five years, and now Hungary, Romania, Brazil, and many others are vying to host Hollywood productions. Quentin Tarantino shot much of "Kill Bill Vol. 1" - including the blood-soaked climax in which The Bride fights off dozens of armed assassins in a Tokyo restaurant - on a sound stage in Beijing, where production costs can be one-eighth what they would be in Los Angeles. Many of the scenes from "Kill Bill Vol. 2" were shot in Mexico for the same cost-cutting reason, including one scene which according to Los Angeles Times journalist Rachel Abramowitz was "shot in a real Mexican brothel, a tattered shack with makeshift tables, and real whores lying in hammocks." It is probably safe to assume that Tarantino did not pay these women union wages.

Critics of runaway productions argue that America is in danger of losing a key manufacturing industry, and insist that because Hollywood is so fundamentally "American" its jobs should stay in the US. But is Hollywood still an American industry? Do Americans really "own" those jobs any more than people elsewhere in the world do? Hollywood has been a global industry since the early 20th century, relying on foreign viewers, foreign earnings, and foreign talent to make its films. Hollywood movies have dominated the global market for filmed entertainment since the late 1910s, and today they take in about 80 percent of the world's total box office receipts. Concomitantly, the viewers of Hollywood movies are increasingly found outside the US: like many other big Hollywood pictures, "Kill Bill Vol. 1" earned much more abroad ($110 million) than at home ($70 million). Hollywood has also been drawing on a global labor market since at least the 1930s, hiring promising actors (Ingrid Bergman, Russell Crowe), directors (Alfred Hitchcock, John Woo), and high-end technical workers (cinematographer Nestor Almendros, "Kill Bill" martial arts advisor Yuen Wo-ping) away from other national film industries. While these global business practices have strengthened Hollywood, they have often provoked angry charges of cultural imperialism and brain drain abroad.

Many who think Hollywood is an American industry claim that even if film production moves overseas, the creativity that drives the industry is still firmly based in the US. But as the studios cut development costs by buying up the remake rights for foreign films, even that assumption is being called into question. A recent screening of "Kill Bill: Vol. 2" was preceded by a trailer for "Shall We Dance?", a Hollywood remake of a popular Japanese movie made in 1996. Judging from this brief excerpt, the remake not only re-used the Japanese film's narrative and characters but also reproduced many of its shots exactly, from composition to camera angles to actor gestures. When paired with Quentin Tarantino's heavy postmodern poaching from the archives of Hong Kong, Japanese, and Italian cinema, this preview raised the question of whose originality and creativity is really being displayed in contemporary "American" movies.

Perhaps we should see outsourcing and runaway productions as signs that foreign film industries are finally finding a way to make global Hollywood work for them. Instead of being merely consumers of Hollywood movies and unremunerated suppliers of Hollywood talent, these industries are becoming paid manufacturers of Hollywood movies. Hosting Hollywood productions may strengthen local film industries, as they build sound stages, invest in the latest camera and sound technology, and develop the sophisticated digital post-production facilities that Hollywood movies require. These investments could provide local film industries with the infrastructural resources they need to make movies with both Hollywood-style production values and distinctive local content - a combination that in South Korea and elsewhere has proven successful at winning audiences away from imported films.

But that potential remains unrealized. Hollywood producer James Schamus, who has two films shooting in Canada and one in Romania, has yet to see any positive impact from runaway productions on local film industries. And film scholar David Bordwell fears that "much of the money local firms get from Hollywood may not be reinvested in local productions but rather in the distribution of US films and the enhancement of the runaway infrastructure," investment options which promise a more secure financial return. The future shape of the global film industry thus remains in doubt. While there are signs of revitalization, we may yet be heading into a situation where there is only one world-spanning film industry, with headquarters in Los Angeles and production and post-production facilities dispersed across the globe. If this comes to pass, national film industries may become little more than branch offices of global - not American - Hollywood, churning out movies that ignore each country's unique local culture.

Christina Klein teaches literature and comparative media studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. She is the author of “Cold War Orientalism: Asia in the Middlebrow Imagination, 1945-1961” (University of California Press, 2003).