Hong Kong As a Clue to the Future China

Hong Kong As a Clue to the Future China

How far and fast is China willing to go in developing the rule of law as well as human and property rights? The United States, in particular, remains uncertain whether China is or will be an international partner or adversary. Perhaps that is why every US negotiator visiting China in 2005, including President George W. Bush, has emphasized China's need to adhere to a rules-based regime of trade and international relations.

The pace and nature of change in China understandably concerns more than China experts. Though it joined the World Trade Organization only in December 2001 as a "developing country", the World Bank and International Monetary Fund independently estimated China's 2004 economy at nearly twice Japan's in purchasing power parity terms and second only to the US. While China's statistics are suspect and purchasing power parity calculations arguable, its global profile clearly has grown. China's willingness to honor its WTO obligations and the willingness of its major trading partners - the European Union, the US and Japan - to accommodate China's growing wealth, power and influence will determine much of the course of the 21st century. Developing China's rule of law and a rules-based internal regime fully honoring human and property rights would be the best guarantors of China's peaceful external behavior in a rules-based international system.

Hong Kong as an international canary

Hong Kong may provide answers to some of these pressing issues. Of a certainty, if Beijing suppresses Hong Kong's rule of law and liberal regime of human and property rights, and if its people reject such moves violently (with consequent repression), prospects for China's peaceful integration into the global political economy must stand in doubt. As China's most economically and politically advanced entity, and as the only part with full WTO membership plus the ability and will to enforce its rules, Hong Kong functions as the China-watcher's canary in the coal mine. Miners long carried caged budgies beside them as they worked the coalface. They knew if the bird died from noxious fumes they were in imminent danger.

Hong Kong as a "canary" is particularly apt for the international community, especially the US. In surveys conducted by the Hong Kong Transition Project just prior to the enclave's return to Chinese sovereignty in 1997, 17% of Hong Kongers reported they had visited the US in the previous decade. One in twenty visited at least annually and 2% had lived in the US at least one year in their lives. (These figures exclude a US citizenry of some 30,000 then, more than 50,000 now.) In 1997, 9% reported relatives living in the US and 42% reported relatives with a right of abode somewhere overseas, not counting Taiwan or Macau. Astonishingly, on the eve of the handover, 38% of Hong Kongers said they spoke English with some facility while only 25% said they spoke Mandarin, China's national dialect.

Hong Kong thus became a part of China decidedly unlike the rest of the country. It is still fundamentally different. Hong Kong's international ties and orientation pose either a unique opportunity for China or a unique threat, and Chinese official attitudes have long vacillated, with caution and suspicion prevailing--making the interaction between the central government and Hong Kong of more than local interest. If China tolerates, even embraces, Hong Kong's international legacy, prospects for its peaceful integration into a rules-based, rights-embracing international regime rise considerably. If it quashes this anomaly in its midst, Beijing's rejection of features central to the prevailing international system will be confirmed. Will China be the first rising major power to integrate peacefully since the 1648 Treaty of Westphalia? Or, like Napoleonic France, Germany, Japan and the USSR in past years, will it try to shape the global order after its own values and priorities? If China is to adapt, its political-economic culture will have to change in Hong Kong's direction.

Arguably, as Hong Kong goes, so goes China. So how goes Hong Kong's relations with mainland China?

How fares the canary?

Hong Kong's 156 years of colonial rule left an indelible appreciation for the British legacy of personal rights, rule of law and limited government. While British rule was by no means perfect, particularly regarding political rights, and while corruption was brought under control only in the 1970s with establishment of the Independent Commission Against Corruption, full property rights and economic freedoms largely prevailed and continue to do so. The attractiveness of Hong Kong's lawful society and enforcement of economic rights, particularly when compared to China, kept a constant flood of illegal immigrants risking life and limb to enter the crowded colony. The value put on protecting that legacy, and threats to it under the new post-colonial rule, largely have determined the course of public satisfaction with the SAR government.

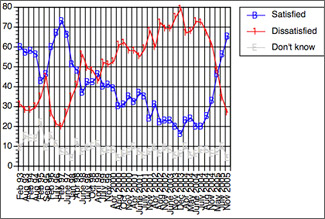

Chart 1 shows satisfaction with the regime of the first Chief Executive, Tung Chee-hwa, never matched that of governors during the final years of colonial rule; this Shanghai-born capitalist was seen more as a representative of Beijing in Hong Kong than as a spokesman for Hong Kong to Beijing. Not until the British-trained civil servant, Sir Donald Tsang, son of a local policeman, took over in March 2005 following Tung's mid-term resignation did satisfaction with government performance exceed that under colonialism.

Worries about encroachment of mainland practices and a possible flood of mainlanders led to the first significant challenge to Hong Kong's rule of law and, with it, rising dissatisfaction with the staunchly conservative, pro-Beijing Tung. In 1999, the Standing Committee of the National Peoples Congress, the Chinese parliament, overturned the Hong Kong Court of Final Appeal's decision that mainland-born children of Hong Kong residents had the right of abode in the former colony. Prior to 1997, the British made strenuous efforts to restrict Hong Kongers from marrying mainland spouses and bringing them to Hong Kong. In 1997, the colonial legal basis for such restrictions disappeared; what appeared to be far more liberal residency provisions of the Basic Law - Hong Kong's de facto constitution - went into force.

Shortly after handover, new court cases sought this right of abode for mainland-born spouses and children of Hong Kong permanent residents. The high court duly ruled that a plain reading of the constitution awarded those rights. But Chief Executive Tung cited a dubious government forecast that 1.6 million mainland relatives would gain right of abode if the ruling prevailed, overwhelming the local welfare and educational systems. This became his justification for a "request" that the Standing Committee overturn the court's decision. While many people feared the Standing Committee's intervention in Hong Kong's legal system on principle, even more feared the practical effects if hundreds of thousands of mainlanders flooded into the tiny territory with one of the highest population densities on earth. These contrasting worries sharply divided the community.

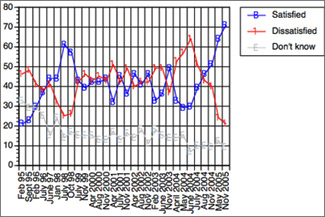

Chart 2 shows that during 1998, his first year in power, satisfaction with Tung's handling of mainland affairs far exceeded that under Chris Patten, the "Last Governor" known for his constant confrontations with Chinese officials over democratization and human rights. When Tung asked the Standing Committee to over-rule Hong Kong's highest court, dissatisfaction went back to pre-1997 levels and stayed there throughout his first term. Even so he was "re-elected" unopposed by the Beijing and business dominated 800-member election committee in March 2002.

Dissatisfaction hit unprecedented levels in 2003 when he proposed legislation to implement Article 23, a clause in the Basic Law requiring Hong Kong to enact, "on its own", laws against treason, secession, sedition, subversion and theft of state secrets. In December 2002, tens of thousands demonstrated for and against pending proposals that went to the Legislative Council (Legco) in February 2003. The SARS outbreak in March temporarily diverted emotions ignited by this issue, but the disease threat also drove home dramatically the economic and personal costs that mainland-style secrecy and suppression could have on Hong Kong. What had seemed abstract issues of importance only to journalists, such as the handling of unauthorized information from official sources, became understood as matters of vital interest after 299 died and thousands fell seriously ill, bringing virtual collapse to economic sectors such as tourism, hotels and restaurants. The SARS outbreak came as a shock, primarily because of secretiveness by authorities in neighboring Guangdong province, compounded by mainland censorship of information about the disease; this drove home what was at stake with press freedom. On July 1, 2003, the holiday marking Hong Kong's reunification with China, over half a million protesters took to the streets, including many from the generally quiescent business and professional sectors.

The subsequent withdrawal of Article 23 legislation and the defeat of pro-government candidates in local elections in November 2003 panicked Beijing into unilateral intervention. In April 2004, the Standing Committee quashed the understanding of many Hong Kongers that they could decide "on their own" to hold full direct elections for all 60 Legislative Council seats in 2008, rather than for only half of them. It ruled that the 50-50 ratio had to be maintained through 2008, and also ruled out direct election of the Chief Executive in 2007. In March 2005, Tung resigned under mainland pressure. A month later the Standing Committee intervened again, ruling Donald Tsang could only complete Tung's five-year term rather than begin a full new one, as the Basic Law seemed to state and as the Hong Kong government repeatedly insisted.

Fears of corruption, crowding, and cultural dilution from the mainland kept Hong Kong's borders tightly controlled after 1997. Only five years of deflation and economic hardship persuaded the public to support a policy change in 2003. Even now, only the smallest land border crossing is open 24 hours per day. Individual travel visas for mainland tourists are limited to 17 mainland cities, most in neighboring Guangdong province. However, with Hong Kongers moving in increasing numbers across the border, and with more engaging in regular travel, older notions that "one country, two systems" means physical segregation are being abandoned. In 1990 fewer than 50,000 Hong Kongers resided on the mainland; today approximately half a million live there, with over 250,000 crossing the border daily. Mainland tourists alone now exceed the 1997 total of 12 million visitors from all countries. In 1980 neighboring Shenzhen had fewer than 40,000 people; today it has an estimated 10 million residents, outnumbering Hong Kong's seven million. It is this growth, along with Hong Kong's dramatic transition from being a manufacturing enclave in 1980 to becoming by 2005 China's pre-eminent international "front office" for finance, tourism and other services that has driven the meeting of systems if not yet minds.

The end of physical segregation in January 2003 was due to realization that increased economic and tourist exchanges had not ruined Hong Kong. Prior to reunification, half those polled in Hong Kong feared Chinese-style corruption would soon prevail there. Only one in five professed no worries. By 1998, fears about corruption had receded, though only a bare majority expressed no worries throughout Tung's eight years in office. After the British-trained Donald Tsang succeeded him in June 2005, fully two-thirds said they had no worry about corruption. On the other hand, Hong Kongers greatest worry about mainland political interference came in 2003 with extremely controversial legislation about security issues, plus two further (unsought) Basic Law "interpretations" by the Standing Committee in April 2004 and 2005. That body, officially a steering committee for the NPC, in reality is a political arm of the Chinese Communist Party and has the power to interpret the Basic Law in any way at any time. For many, this subjects Hong Kong's legal system to a constant threat of mainland intervention. Nevertheless, public opinion toward the central government remained positive until the unilateral intervention of 2004. Sentiment did not recover until Beijing began to state that constitutional reforms, while limited, could be more substantial than first indicated, and until Tsang replaced Tung in March 2005.

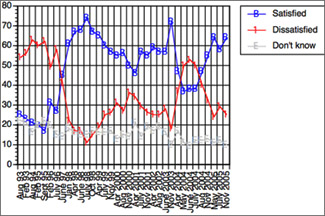

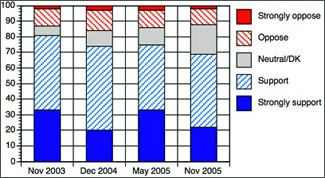

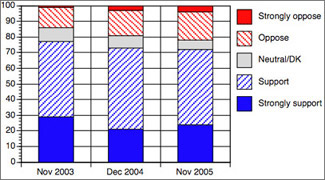

During all this controversy, support for direct election of the Chief Executive and for all members of Legco remained very high, as Chart 4 and Chart 5 show.

Chart 5 indicates some rise in opposition to a fully directly elected legislature. This rise may be due to dissatisfaction and frustration with continuing confrontation between the executive and legislature over reforms.

The "ultimate aim", according to the Basic Law, is that the Chief Executive and all Legco members will be chosen by universal suffrage. Toward that end, the Basic Law laid out a timetable of change from 1997 to 2007-08. After that, according to a nominal reading of the law, Hong Kong people themselves could decide how to achieve those aims for the legislature and, in consultation with the central government, for the chief executive. These were understood as key components of Deng Xiaoping's promises of a "high degree of autonomy" and "Hong Kong people ruling Hong Kong." Over time, these promises have become taken by the people as writ and, increasingly, as overdue. Dismayed by unfulfilled promises of reform and accountability under Tung's system, and heartened by results of massive street demonstrations and the elections of 2003 and 2004 that eventually drove the deeply distrusted Tung from office, Hong Kongers became increasingly impatient with delay. Incremental reforms which brought steps toward full direct elections and democratic citizenship seemed too small and infrequent.

The bottom line is that 57% support both direct election of the Chief Executive and of all members of the legislature, while only 8% oppose both in principle. Two thirds want both accomplished by 2012. The issue of when has become the stumbling block that may result in a constitutional crisis, the resolution of which will determine the international canary's fate and, with it, whether China will conform to or confront the international system of rule of law and human rights.

Confrontation may loom because a constitutional crisis appears imminent following the legislature's rejection of Tsang's modest reform proposals. As of this writing, some observers have been reassured by China's WTO entry and subsequent actions to open its markets, move toward a convertible currency, strengthen market regulatory regimes and crack down on intellectual property rights violators. Others worry that the shift of political power from former President Jiang Zemin's "third generation" to President Hu Jintao's "fourth generation" might see China go off the reform rails. Hopes that Hu would usher in political reform while continuing economic reform already have been dashed, while central government intervention in Hong Kong politics has raised fears China will drastically slow or quash Hong Kong's democratic development, despite Basic Law promises to the contrary. It is not clear whether China will honor rules that require protection of property rights and a fair, impartial adjudication of contractual disputes between local and international investors, plus the Basic Law commitments to implement full universal suffrage in Hong Kong. These crucial tests will determine whether China is moving to accept of an international system founded on the rule of law. Hong Kong, the canary in the coal mine, holds its breath.