Horsing Around the Global Food Chain

Horsing Around the Global Food Chain

NEW HAVEN: “Waiter, there’s a horse in my soup!” For European consumers who enjoy the convenience of frozen precooked meals like lasagna, this is no longer an unsavory joke. Europeans are angry about globalization and suspicious of its products. Along with horsemeat, a powerful anti-inflammatory drug phenylbutazone, normally administered to horses as a pain treatment, has entered the European food chain, triggering investigations and soul-searching about the efficacy of governance in an intricately interwoven world. As with previous cases of fraud and poisoning of processed foods and beverages in globally traded products, the horsemeat saga once again throws the spotlight on an emerging reality: For a safe and sustainable global supply chain, there’s no substitute for effective local governance.

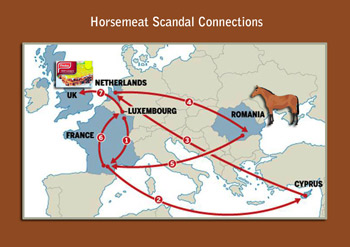

The scandal erupted in mid-January when British food inspectors discovered horse DNA in packages of beef lasagna marketed by Findus Group, headquartered in Britain. Initial investigations unraveled a spaghetti-like supply chain linking at least five European countries that had managed to re-label the less expensive horsemeat as beef: Findus placed orders for lasagna, cannelloni, spaghetti bolognaise and moussaka at a Luxembourg-based French company Comigel, which had contracted with the French processing company Spanghero to source beef. The contract went to a Dutch trader based in Cyprus. The Cypriot company in turn outsourced the order to a Dutch company which subcontracted another company. The order ultimately landed with a Romanian abattoir that supplied minced meat to Spanghero. According to Benoît Hamon, the French deputy minister in charge of consumer affairs, Spanghero mislabeled Romanian horsemeat as beef. By substituting horsemeat for beef, Hamon said, Spanghero may have made a €550,000 profit.

Since this chance discovery of mislabeling in Findus lasagna, more cases have been exposed – an Irish company sold mislabeled Polish horsemeat, and several UK companies have marketed horsemeat as beef burgers and kebabs. By the latest account, some 750 tons of horsemeat have gone into 13 European countries of which 550 tons were used in the manufacture of more than 4.5 million meals. According to the French minister, fraudulent sales of horsemeat had been going on for months.

UK government testing has shown that little over 1 percent of declared beef products were horsemeat – enough to have shaken consumer confidence in precooked supermarket meals. Supermarkets have withdrawn beef Bolognese sauce, beef broth soup, meat pasta sauce and chili con carne suspected of containing horsemeat. From being a straightforward case of mislabeling or fraud, the scandal took a more ominous turn last week when the UK’s Food Standards Agency said phenylbutazone, a drug potentially harmful to human health, was identified in carcasses of horses, some of which were exported to France. There’s no taboo attached to horsemeat in Europe; restaurants put it on menus and serve it to customers. And although the British government’s chief medical officer has discounted the risk of ingesting a dose that could be harmful to humans, the revelations have left a bitter taste with consumers. If horsemeat was sold under the label of “100 percent pure beef,” what else have consumers been fed that’s yet to be revealed?

The horsemeat scandal has highlighted a dark side of the globalized economy. The 2008 global financial crisis that encompassed the European Union triggered a deep economic recession that affected all aspects of life. Many horse owners, fallen on hard times, abandoned their animals. Instead of incurring the costs of euthanizing them, owners sent the animals to abattoirs to bring in needed cash. In Ireland, the European country with the largest concentration of horses, some 25,000 were sent to slaughterhouses in 2012. The economic crisis accounts for a tenfold increase in the slaughter of horses during the past four years, resulting in a sharp drop in the price of horsemeat. On the other side of the continent, the 2007 Romanian ban on horse-drawn carriages on highways had a similar effect, accelerating the slaughter of horses. Leaner horsemeat, which costs half the price of beef, found its way into the food chain.

Globalization of prepared food, increasingly popular for working-class families looking for fast, easy and affordable meals, has for its part stepped up the pressure on primary suppliers. Companies like Findus and Spanghero, trying to supply supermarkets with ever-cheaper packaged food, have attempted to secure profit margins by squeezing farmers and suppliers down the line. Unlike high-end organic food, sources of which can be traced to the growers, frozen foods intended for poorer consumers have been produced with limited supervision and control. Industry resists quality control as that costs money. The inevitable result has been cutting corners and perhaps even outright fraud.

Consumers, schoolchildren and hospital patients are not the only victims of the supply-chain failure; 320 workers of Spanghero have been laid off as the government suspended its license, pending investigation of the company’s role in the mislabeling. The suspension order is a “death sentence” for residents of Castelnaudary, where one is either employed by Spanghero or probably not employed at all. The small town is situated in France’s third poorest region, where the unemployment rate stands at 13.5 percent. Whether the executives are found guilty or not, the future of that company, or for that matter, distributors like Findus, looks grim. In this hyper-connected age, the bad reputation of a supplier spreads at the speed of light and it could take the company involved years to recover. In 1990 there was a scandal involving benzene found in a few bottles of French-produced Perrier. Despite the decision to withdraw its entire worldwide stock of 160 million bottles, the company’s image was gravely damaged. It took Perrier 15 years to recover its transatlantic market share.

The horsemeat scandal has exposed, once again, the risks of long and complex supply chains involving dozens or more suppliers, where the search for a better price results in careless quality control. The French newspaper Le Monde calls the horsemeat scandal the “Pasta subprime,” a comparison that recalls the disastrous bundled debt containing toxic US subprime assets that brought global financial market to the verge of collapse. Comparing fraudulent use of mislabeled food that affects a sliver of the market to the subprime fraud may be excessive, but it raises legitimate issues of supervising a closely integrated market for the well-being of all consumers.

As bankers and rating agencies allowed subprime mortgages of questionable value to be bundled for their private gains, some actors in the frozen food supply chain have done the same. To ensure their own profit, one of the links in the long supply chain was contaminated, leading to the collapse of the entire chain. Similar failures have occurred repeatedly, as in the case of China’s melamine-tainted formula for babies in 2008, causing death and injury.

Given the complexity of production systems with components crisscrossing international borders and increasing pressure for cost-cutting, the need for supervision is greater than ever. Unless local authorities take on a greater responsibility to ensure safety and hygiene of ingredients and components produced for global consumption, the economy and workers will suffer as much as consumers beyond local borders. Packaged foods in the supermarket shelf may be global, but the responsibility for consumer safety everywhere is ultimately local.

Nayan Chanda is editor of YaleGlobal Online and co-editor of A World Connected: Globalization in the 21st Century.