How to End the Forever War

How to End the Forever War

OXFORD: From both the left and the right, three common misperceptions have emerged about US foreign policy: First, that the Global War on Terror has become a perpetual state of affairs; second, that no strategy is available to end this conflict in the near future; and third, that “the Obama approach to that conflict is just like the Bush approach.” I disagree with all three propositions.

First and most important, the overriding goal should be to end this Forever War, not engage in a perpetual “global war on terror,” without geographic or temporal limits.

Second, this is not a conflict without end, and there is a strategy to end it, outlined below. In November, also at the Oxford Union, Jeh Johnson, then general counsel of the United States Department of Defense, argued that in the conflict against Al Qaeda and its affiliates:

"there will come a tipping point – ... at which so many of the leaders and operatives of al Qaeda and its affiliates have been killed or captured, and the group is no longer able to attempt or launch a strategic attack against the United States, such that al Qaeda as we know it, the organization that our Congress authorized the military to pursue in 2001, has been effectively destroyed. At that point, we must be able to say to ourselves that our efforts should no longer be considered an “armed conflict” against al Qaeda and its associated forces; rather, a counterterrorism effort against individuals who are the scattered remnants of al Qaeda, or are parts of groups unaffiliated with al Qaeda…."

The key question going forward will thus be whether the US treats new groups that rise up to commit acts of terror as “associated forces” of Al Qaeda with whom it’s already at war. This seems unwise, as under both domestic and international law, the United States has ample legal authority to respond to new groups that would attack without declaring war forever against anyone hostile to the country. More fundamentally, the United States is at war with Al Qaeda, not with any idea or religion, or with mere propagandists, journalists or sad individuals, like the recent Boston bombers, who may become radicalized, inspired by Al Qaeda’s ideology, but never joining Al Qaeda itself.

Third, in regard to this conflict, the Obama administration has differed from its predecessor in three key respects. First, it has acknowledged that the United States is strictly bound by domestic and international law. Under domestic law, the administration has acknowledged that its authority derives from Acts of Congress, not just the president’s vague constitutional powers. Under international law, this administration has expressly recognized that US actions are constrained by the laws of war, and it has worked hard to translate the spirit of those laws and apply them.

The Geneva Conventions envisioned two types of conflict – international armed conflicts between nation-states and non-international armed conflicts between states and insurgent groups within a single country, for example, a government versus a rebel faction located within that country. But September 11 made clear that the term “non-international armed conflicts” can also include transnational battles, for example, between a nation-state like the United States and a transnational non-state armed group like Al Qaeda that attacks it. The US Supreme Court has instructed the US government to translate the existing laws of war to this different type of “non-international” armed conflict.

Second, in conducting this more limited conflict, the administration has shown an absolute commitment to humane treatment of Al Qaeda suspects. Third, the Obama administration has determined not to address Al Qaeda and the Taliban solely through the tools of war. Instead, this administration has stated a longer-term objective – a “smart power” approach – under which force is used for limited and defined purposes within a much broader nonviolent frame, with the over-arching aim being to use diplomacy, development, education and people-to-people outreach to challenge Al Qaeda’s ideology and diminish its appeal. Applying this approach, the Obama administration has combined a law-of-war approach with law-enforcement methods to bring all available tools to bear against Al Qaeda. In a remote part of Afghanistan, a law-of-war approach might be appropriate, but in London or New York, a law enforcement approach is surely more fitting. In either case, the US response to a suspect turns not on whether we generically label a person an “enemy combatant," but on whether we assemble the facts to prove that a particular person’s behavior reveals that he is part of Al Qaeda.

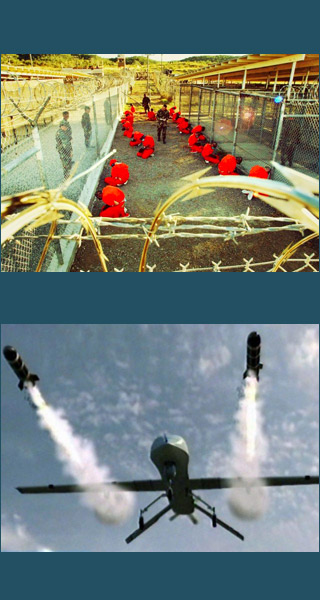

So how to end the Forever War? President Obama should now diligently pursue three previously announced aims of US policy: 1) disengage from Afghanistan, 2) close Guantanamo and 3) discipline drones.

Disengaging from Afghanistan is fully underway, but three challenges loom. First, in transferring control of detention facilities, the US must ensure that transfers comply with obligations under international law not to return detainees to persecution or torture, and that future detentions comply with fair process and treatment obligations. Second, the US must work closely with the Afghans to help secure what Secretary of State John Kerry has called a “credible, safe, secure, all-inclusive, … transparent, and accountable presidential election” to succeed Hamid Karzai in 2014. Third, the Afghan government must tackle the controversial task of negotiating with the Taliban. In so doing, it’s crucial to build upon the myriad advances that have expanded individual freedom within Afghan civil society over the last decade.

Closing Guantanamo permanently is long past overdue. The US military prison in Cuba has 166 detainees, 76 fewer than in 2009. More than 100 of the detainees are on hunger strike, with many being force-fed. President Obama has acknowledged, “Guantanamo is not necessary to keep America safe. It is expensive. It is inefficient. It hurts us in terms of our international standing.”

Crucially, he does not need a new policy to close Guantanamo. He just needs to put the full weight of his office behind the sensible policy first announced in 2009: Resume transfer of those who are cleared for transfer, try the triable, grant periodic review of those in law of war detention, resist further congressional restrictions and appoint a high-level White House envoy to implement the foregoing.

The goal of decimating Al Qaeda's core leads to the final contentious issue, disciplining drones. Critics often ask, “How, as a human rights advocate, could you criticize torture, while as a government lawyer, you defended the legality of drones?” The answer is sad, but simple: Torture is always unlawful. But killing those with whom a country is at war may be lawful, so long as the laws of war are strictly followed. It is the duty of government lawyers to police the line between those violent acts that are lawful and unlawful, and distinguish between those uses of force that do and do not on balance promote the human rights of innocent civilians.

Drones are not per se unlawful. If accurately targeted, they could be far more discriminate and lawful than indiscriminate weapons. The main problem is not drones, but that the Bush administration grossly mismanaged its response to 9/11. Instead of acting surgically against Al Qaeda when it had the chance, the administration squandered global goodwill by invading Iraq, committing torture, opening Guantanamo, flouting domestic and international law, and undermining civilian courts.

Left to pick up the pieces, Obama got off to a promising start, but that effort has slowed. Since 2010, the Obama administration has not done enough to be transparent about legal standards and its decision-making process. Small wonder that the public has lost track of the real issue, which is not drone technology per se, but the need for transparent, agreed-upon domestic and international legal process and standards. The Obama administration should now make public and transparent its legal standards and institutional processes for targeting and drone strikes, give facts to show why past strikes were necessary, and consult with Congress and allies on principled standards going forward. Most important, he should oppose proposed legislation that would grant him unneeded new authority to strike new shadowy foes.

The real and pressing issue facing the United States is how to end the Forever War underway since 2001. If the Obama administration cannot persuade its citizens, Congress and its closest allies that its drone program is legal, necessary for that task and under control, it will be hard for President Obama to see that war to its much-needed conclusion or take the other steps needed to secure the peace.