How a One Drink Changed Fortunes, Incited Protests

How a One Drink Changed Fortunes, Incited Protests

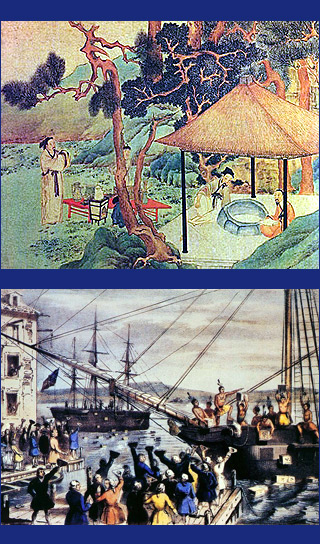

NEWARK: More than 250 years ago, as irate colonists threw boxes of tea into Boston Harbor little did they imagine that their angry act would change history or come to symbolize political revolt inspiring later generations. Thanks to globalization, shriveled leaves of tea from faraway China, once brought by the East India Company, continue to shape history. Each refreshing cup represents happier aspects of international business. But the globalization of tea also carries a history of international intrigues, monopolies, wars and ethnic displacements.

Until 350 years ago, tea was a relatively rare libation made from a little bush, Camellia sinensis, originating in the hilly provinces of southern China such as Yunnan. Consumed only by a few Buddhist monks, or Chinese and Japanese aristocrats, it was more or less unknown to the rest of the world, although small shipments may have made their way – as curiosities or medicine – along the Silk Road to India and the Middle East.

The first bulk exports were made by the Dutch who transshipped Chinese tea from Java to Holland starting in 1606. Newfound prosperity and a rising middle class in Holland made up the first large-scale market for tea in the 17th century. For the rest of Europe – even the nations to the north that eventually became the United Kingdom, which today has the highest per-capita consumption – tea remained unknown until Catherine of Braganza, a Portuguese princess, arrived to marry Charles II of England. Stepping ashore at Portsmouth, in 1662, after a difficult channel crossing, Catherine asked for her favorite drink. But none was available. The nonplussed English offered her a glass of ale instead, which did little to settle her stomach. But the court set the fashion, and tea drinking spread among the English nobility. Only the rich could consume it since, based on mercantilist principles, British tariffs were punitively high, ranging at one time as high as 119 percent ad valorem.

The high tariffs were needed to fund the Franco-English war that began in the American colonies in 1754 and then spread to Europe and India, with fighting as far eastward as Indonesia – some Eurocentric historians label the 1754-1763 war as the “first world war,” although the conquests of Genghis Khan by the year 1225 covered more degrees of latitude and an incomparably greater fraction of mankind from Hungary to Korea and from Russia to Iraq.

The American patriots – some call them ruffians led by Samuel Adams – who threw the cargo of British imported tea into Boston Harbor protested the high tariffs and monopolized trade by the East India Company. Even as tea drinking gained steady popularity in the UK, it was considered unpatriotic and declined in America.

By the late 18th century, the British faced a mercantilist dilemma. The Chinese – sole suppliers of tea to the world – refused to import much from the West. The Chinese trade surplus had to be financed in silver and bullion shipped out from England, in exchange for the monopoly product. It was a case of a British import monopsony versus the Chinese monopolist producer. High UK tariffs did not stem the drain of silver, as these may have only induced more tea being smuggled than imports obtained through official channels.

Finally, the East India Company had an idea to solve the drain of bullion going to China, investing in plantations to grow opium in Bengal and the Deccan Plateau of India. It’s said by anti-colonialists that this also dealt a blow to Indian cotton cultivation and its workers. This opium was not for Indian consumption, but intended as an export to China. Naturally, the Chinese government was horrified and prohibited this import, only to have the British declare war, insisting that Chinese tea be exchanged for Indian opium and not for precious metal. One of many cases of “gunboat diplomacy,” the move won Hong Kong for the British and the right to sell opium to the Chinese, but caused a legacy of social problems, with thousands of Chinese being addicted. The humiliation at the hands of the British rankle to this day in the minds of many educated Chinese.

Meanwhile, Robert Bruce, a Scotsman who lies buried in the Indian town of Tezpur, discovered a variety of the tea bush in the Himalayan foothills of Assam, a state in Northeast India then populated by Tibeto-Burmese tribes such as the Bodos. The find proved to be a close substitute for the Chinese cultivar, and India’s tea exports supplanted those of China by the 1860s. But this came at a large cost in further human suffering.

In the heedless fashion common during the colonial era, the British moved tens of thousands of indentured laborers from other poorer states in India to work the tea estates in Assam, since the indigenous population was content in its own culture and unwilling to work as plantation labor. There followed traders, railroad workers and other enterprising Indians who took over and displaced the Tibeto-Burmese indigenes. The ethnic tensions and conflicts culminated in separatist movements and terrorism that simmer beneath the surface in Northeast India to this day.

The highlands of Ceylon, today’s Sri Lanka, also proved salubrious to the tea bush. Few of the proud and relatively well-off Singhalese deigned to work as plantation labor, so the British imported tens of thousands of Tamils from India to work in their tea and rubber companies in Ceylon – a population that never assimilated with the native Buddhist Singhalese. This induced migration directly led to the just-concluded civil war in Sri Lanka that has left nearly 100,000 dead, hundreds of thousands injured and millions of refugees.

From Ireland, to Israel/Palestine, to Guyana, to Fiji, to China, Assam and Sri Lanka, migrations induced by British colonialism and commerce have left a legacy of ethnic tension, conflict and tears.

But using the narrow ethical lens of the 21st century, we may be too harsh in our judgment. We can rejoice that our global standards today are higher, thanks to the globalization of ideas. The same globalization that still causes angst and ethnic tensions also contributed to world prosperity. Trade and foreign direct investment have lifted literally billions into a middle-class status, and tea remains one of their favorite beverages. When the world history of the 19th and 20th centuries is written in future millennia, all the wars, terrorist incidents and conflicts may be reduced to a passing mention or footnotes. But one salient fact will be recorded – the emergence of billions of humankind from agrarian backwardness to productivity, from ignorance to enlightenment, from poverty to a middle-class status, as a result of globalization. Companies from nations such as China or India have emerged to rival the multinationals of the West.

The natives of a land where tea thrives had their revenge in the year 2000. In an acquisition redolent with symbolism for the future, the UK’s leading tea company, Tetley Tea, was taken over, a “reverse” investment, by the Tata Group based in India.

Farok J. Contractor is professor of management and global business at Rutgers University in New Jersey. His latest book, “Global Outsourcing and Offshoring: An Integrated Approach to Theory and Corporate Strategy,“ was published by Cambridge University Press in 2010.