Illegal Immigration Illogic

Illegal Immigration Illogic

NEW YORK: At a time when the United States is unsure what to do with its 12 million illegal immigrants, the country is beset by a dilemma caused by a deluge of new wave of immigrants – unaccompanied children. To simply send them back without tracking their families or investigating the circumstances is not only inhumane, but in some cases could violate international law. Yet allowing them to remain undermines the rule of law and the legal system that protects the country’s borders from illegal flows of migrants.

The US Border Patrol has apprehended more than 85,000 unaccompanied minors at the southwest border during the past two years. The nub of the dilemma stems from conflicting logic – hard attempts to protect the border from the flow of migrants and equal difficulty in repatriating children once they are in. The dilemma is not America’s alone – refugee children move alone in Asia and Africa, and Europe reported more than 12,000 children registered for asylum status in 2009. A volatile mix of politics, economics, special-interest groups and demographics worldwide has produced troubling pressures as millions of illegal immigrants challenge governments, frustrate constituents and harden worrisome ethnic divisions.

Official policy regarding illegal migration is clear: Illegal migration is not tolerated, and illegal migrants are deported. In reality, illegal migration is widely and illogically tolerated by governments with many migrants not deported and amnesty or regularization often offered by authorities after the passing of some years. In brief, despite official policy the de facto message and understanding of men, women and children including smugglers and traffickers in immigrant-sending countries as well as the implicit principle guiding many governments of receiving countries is: If you can get in and keep a low profile, you can stay.

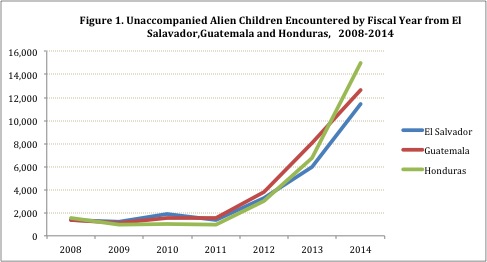

Reactions to immigrants are less clear-cut, often hinging upon personal details and an individual’s life story. The surge of unaccompanied alien children from El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras unlawfully entering into the US tests both sides of the immigration debate. Between 2008 and 2011, the numbers for the three Central American countries were relatively stable, generally fewer than 1,500 unaccompanied alien children per year (see Figure 1).

Starting in 2012, the numbers of unaccompanied children from these three countries increased rapidly.

International law, Article 13 Universal Declaration of Human Rights, recognizes the human right to leave one’s country and return. International law does not include a human right for someone to enter another country and certainly does not intend to entice children to leave families and communities.

Images of child migrants, detained and warehoused, demonstrate that drafting laws is easier than enforcement.

Most governments apply laws and legal procedures to process growing numbers of cases. Some migrants and their supporters tend to overlook or downplay that they are in violation of the law, often using confusing terminology such as “irregular” or “undocumented” migrants, lumping together legal and illegal migrants. For some, the legal deportation or repatriation of illegal migrants has taken on the connotation of a violation of basic human rights, an immoral, mean-spirited or discriminatory act.

A major reason for illegal migration is that the supply of potential migrants greatly exceeds demand for migrant labor in immigrant-receiving countries. Poverty, unemployment, lack of social services, political instability and conflict contribute to illegal migration in both developed and developing countries. Men, women and children living in horrific conditions understandably risk their lives to migrate.

Clearly, illegal migration is not a realistic solution for the hundreds of millions living in dire circumstances.

Some maintain that the current surge of unaccompanied children is largely due to high levels of crime and violence in home countries. Others point to rumors and a widespread belief that US administration will permit children entering illegally to remain, with or without families, many of whom are also illegal immigrants.

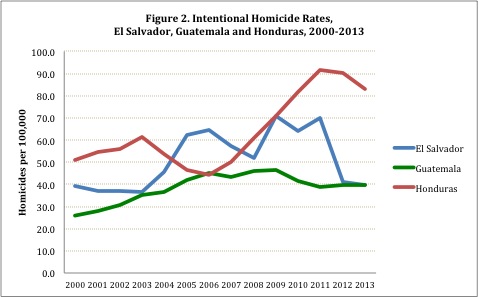

While violent crimes are especially high among these three Central America countries, the surge of unaccompanied children does not appear to be the result of increases in crime rates. Intentional homicide rates for El Salvador, Guatemala and Honduras, for example, do not show a sudden jump in 2012. If anything, rates may be declining somewhat (Figure 2).

Likewise, GDP per capita, while low, is on an upward trend for the three countries. Fertility rates are in decline. But in a globalized world, both poverty and fertility rates remain comparatively high.

A more plausible explanation for the recent surge appears to be a flimsy hope, reinforced by smugglers, that the unaccompanied children will be allowed to stay in the United States. This belief may be due in part to Obama administration announcements, including the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program announced in June 2012, which offers temporary status to some children who arrived before 2007. Subsequent actions by the Obama administration permit large numbers of illegal migrants to remain in the US, especially those without criminal violations.

In the United States, one quick fix is adjusting a trafficking law that would allow fast deportation of children, reducing investigations and hearings, similar to how children from Canada and Mexico are now managed.

When the numbers of illegal migrants residing in a country are relatively small, the matter might be ignored or quietly resolved by responsible agencies. But large numbers of children require swift government action.

A precise global figure on the number of illegal migrants is difficult to establish. The number varies from time to time due to amnesty, regularization or normalization programs. For example, Spain in 2005 regularized 700,000 illegal migrants, granting them legal status. Over the last several decades Belgium, Canada, France, Greece, Italy, Portugal, Spain and the United States, have implemented amnesties or regularizations aimed at reducing the number of illegal migrants.

Worldwide, the total number of illegal migrants is at least 50 million. Countries assumed to have the largest numbers include the United States with 12 million; India, at least 10 million; South Africa, 10 million; the Russian Federation, 4 million; the United Kingdom, perhaps nearly 1 million; Malaysia, 800,000; Brazil, about 500,000; and the Republic of Korea, at least 300,000.

Arguments against deportation often center on practicality – with huge financial and administrative costs required for identifying, processing and sending illegal migrants home. Deportations may lead to disruptions for the economy and labor force, especially in agriculture and industries that rely on the low-cost labor, often operating outside the formal labor force.

Human rights and humanitarian concerns also give rise to legal and ethical questions regarding repatriation of illegal migrants, especially when families are divided, or people are returned to home countries with high rates of poverty, unemployment and violence.

The general public is by and large supportive of legal immigration, especially for immediate family members and needed workers. This support, however, is being undermined by ineffective controls of illegal immigration and weak enforcement of relevant laws regarding unlawful residence and employment, including the legal, efficient and humane removal of those determined to be unlawfully resident. Moreover, many are not inclined to reward people who have broken immigration laws with citizenship, creating incentives that only encourage more illegal immigration.

Until governments can resist illegal immigration illogic, they will continue to be confronted by growing numbers of illegal migrants as well as a frustrated and alienated general public.