Increased Globalization Pivotal to Japanese Reform

Increased Globalization Pivotal to Japanese Reform

If Japan is to reform, increased globalization will have to play a critical role. This is not only because, across the world, where reform has succeeded, an increase in competing imports and foreign direct investment (FDI) has been indispensable. It is because insufficient globalization is at the heart of Japan's problems; hence, increased globalization must be at the heart of the solution.

Japan's relative insularity stands at the root of its intractable malaise. The biggest cause of Japan's stagnation is not lack of demand, but declining potential growth. From 1975-90, Japan grew 4% a year. Today, even at full capacity, its long-term potential growth has plunged to only a bit more than 1% and, according to the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development (OECD) is on track to descend to 0.5% potential growth by 2010.

The main problem is that there is not one Japan, but two. Japan suffers from a unique "dual economy" - a dysfunctional hybrid of super-efficient exporting industries and super-inefficient domestic sectors. The exporters are competitive because they face competition on the international stage. The domestic sectors are shielded from both imports and domestic competition. Cheaper Korean steel is blocked, not by formal barriers but by cozy deals among steelmakers and their customers.

The domestic sectors' relative insularity from international competition serves as the bodyguard for domestic anti-competitive practices. If competing imports and foreign firms could reach critical mass on Japanese soil, then domestic anti-competitive practices would be unsustainable. Naturally, the lack of competition atrophied the economic muscles. In food processing, for example, Japan's productivity is one-third of U.S. levels and falling further behind. Yet more people work in food processing than in cars and steel combined.

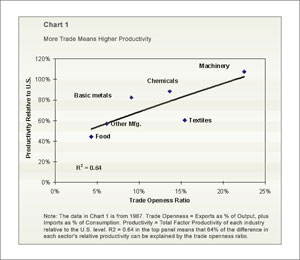

International trade competition, or lack of such, is a clear dividing line between the efficient and inefficient sectors of the Japanese economy. The best measure of efficiency is what economists call Total Factor Productivity, i.e. not just the productivity of labor, but of capital as well. If we look at the ratio of total trade (exports plus imports) to the output of an industry, there is a remarkably strong connection between trade and efficiency. The higher the ratio of trade to output, the higher the industry's TFP. In fact, there is a 64% correlation between a sector's trade:output ratio and its level of TFP relative to its U.S. counterpart (see Chart 1).

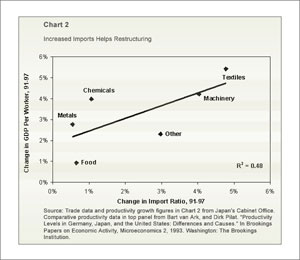

Fortunately, increased globalization has proved to be a powerful antidote to inefficiency. Industries such as textiles/apparel that were willing to expose themselves to the crucible of international competition improved their performance dramatically. During the last decade, there was a nearly 50% correlation between increased import penetration and improved output per worker (see chart 2).

Inward foreign direct investment (FDI) is just as critical as competing imports because foreign firms operating on Japanese soil can often change the behavior of key Japanese players. For example, up until regulatory reform in the early 1990s, Toys R Us was legally blocked from establishing a single store in Japan. Now, with more than 100 stores, they are Japan's largest toy retailer. Its entry weakened the power of manufacturers over retailers and thus over retail prices, thereby increasing consumer power. Traditionally, 80 percent of toy retailers sold at prices equal to or above manufacturers' suggested list prices. By the mid-1990s this had dropped like a rock to only 30 percent, as Japanese retailers were forced to discount in order to compete with Toys R Us. Reductions in monopolistic prices caused by increased competition frees up money to be spent on other items. This helps alleviate Japan's chronic deficiency of aggregate demand by adding to consumer purchasing power.

The good news is that Japanese reformers are beginning to see globalization as an ally. Hence, there has been substantial improvement on some fronts - especially FDI and financial integration. Unfortunately, there has been almost no improvement in competing imports.

Insular Japan

A century-and-a-half ago, Japan pioneered the trade-led development strategy for "Third World" countries. How ironic, then, that Japan is now perhaps the least globalized of all the industrialized countries - as measured by the role of trade in its economy.

Alone of all mature economies, Japan trades less today relative to Gross Domestic Product (GDP) than it did five decades ago. Today, exports and imports together amount to only 20% of Japan's nominal GDP. Back in the late 1950s, the trade-to-GDP ratio averaged 23%.

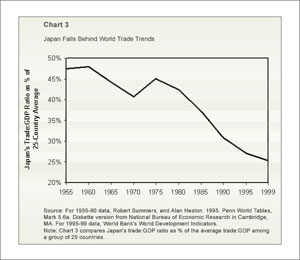

This makes Japan unique. In other rich countries, the trade-to-GDP ratio has doubled or tripled since the 1950s, in the U.S. case going from 9% to 26%. By standing still, Japan fell behind global trends toward greater interdependence. In the 1950s and 1960s Japan's trade-to-GDP ratio was about 45 percent of the average among a group of twenty-five rich and newly industrializing countries. By 2000, Japan's ratio was down to 25 percent of the group average (see Chart 3). If Japan had simply kept up with global trends, both its exports and its imports would be almost twice as high as they actually are. Japan not only imports too little; it also exports too little.

Not only is the volume of Japanese trade at odds with international trends, so is the composition of the trade. The index of its intra-industry trade--i.e. willingness to import the same goods its exports, such as steel, machinery and autos--is inordinately low. Typically, as countries develop, there is a rise in the intra-industry trade index (which ranges from 0 to 1). Korea, for example, went from an intra-industry trade index (IIT) of 0.19 in 1970 to 0.48 in 1990. In France, often labeled protectionist, the IIT index was 0.84 as of 1990. In stark contrast, Japan's index was 0.36 in 1990, barely higher than the 1970 level of 0.33. It had a lower IIT index than almost all the developing countries of Asia except Indonesia.

Japan is equally an outlier when it comes to accepting inward foreign direct investment. In 1999, Japan's inward FDI was only one-ninth the 2.7% of GDP exhibited in the typical developed OECD country. On a cumulative basis, the comparison was even worse; less than one percent of Japanese GDP in 1998 came from foreign direct investment, compared to 16 percent in the United States and 26 percent in France.

In measuring Japan's progress in overcoming this insularity, we need to look along three axes: competing imports, increased FDI and financial integration.

Competing Imports

On the surface, it seems as if there is dramatic progress on the import front. Imports of manufactured goods, which hovered for years at only 12 percent of total consumption of manufactured goods, suddenly rose in the 1990s, virtually doubling to 23 percent by 1999. Moreover, economists report a significant improvement in intra-industry trade between 1986 and 1998.

Unfortunately, all of the last decade's increase in manufactured imports was provided by Japanese affiliates operating overseas, e.g. imports of Matsushita TVs made in Malaysia, rather than Samsung TVs made in South Korea. Manufactured imports from non-Japanese sources actually fell in the last decade.

Unfortunately, such "captive imports" are not designed to challenge the price structure and cozy ties of the Japanese electronics industry. A South Korean TV is. And it is competition that provides the productivity kick Japan so desperately needs.

True, interfirm trade is important elsewhere. However, in most industrial countries, interfirm trade supplements and stimulates their overall trade. In Japan these days, interfirm trade is, to a considerable degree, substituting for other trade.

Inward FDI

When it comes to inward FDI, Japan has exhibited a remarkable sea change. A decade ago foreign acquisition of any large Japanese firm was unheard of. Today just about every auto firm other than Toyota and Honda is now under the effective control of foreigners. After one of Japan's largest banks, the Long-Term Credit Bank (LTCB), went bankrupt, the Japanese government sold it off to a U.S.-based investment consortium, Ripplewood. However, this caused such an uproar that the government acted to prevent bankrupt Nippon Credit Bank from also being taken over by a foreign player.

Skeptics point out-correctly-that almost all the acquisitions so far have been rescue operations for distressed firms. If inward FDI is to take off, it must become easier for foreigners to buy healthier firms, either parts of them or entire companies.

Nonetheless, even with the remaining impediments, FDI into Japan has multiplied from 0.1 percent of GDP in the early 1990s to 0.4 percent of GDP by 2001. The fields of finance, autos, electronics, telecommunications, and retail/wholesale head the list of investments. Even if the annual inflow were to go no higher than the peak 0.6 percent of GDP attained in fiscal year 2000, cumulative FDI would still rise to almost 6 percent of GDP by 2010. That's ten times today's level.

Financial Integration

Financial integration is critical because it increases the odds that money will be allocated according to its most efficient use, not outdated ties. In addition, increased financial integration of stock and credit markets makes it harder for authorities to cover up problems via financial manipulation.

As with FDI, there have been remarkable changes in recent years.

Japan Inc. is now a joint venture; foreigners now own stocks amounting to 20 percent of the value of firms listed on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. A decade ago, foreign ownership was 5 percent. On any given day, foreign investors conduct up to 40% of all stock trading. Their optimism or pessimism about Japan and Japanese firms is the critical swing factor in stock prices. Not until 1986 were foreign brokers allowed to buy seats on the Tokyo Stock Exchange. Yet today, foreign-affiliated brokers handle 40-50 percent of the buying and selling of Japanese stocks.

Asset management, particularly pension fund management, is an enormous business, with all the public and private pension funds adding up to a fifth of total household assets. As late as 1995, foreign presence in the pension fund market was negligible. But by 1998, as a result of internal deregulation and U.S.-Japan negotiations, there was a quantum leap. Foreign trust banks and investment advisers managed 6 percent of the $410 billion in the corporate-run employee benefit plans, a share that rose to 15 percent by March 2000. In 1998, they managed an even higher 12 percent ($210 billion) of the privately managed portion of public pension plans. Their share soared to 22 percent by March 2000. Currently, only a fifth of the public pension funds are managed privately, but this figure is a big increase from the past and further increases are expected. In the years to come, foreign firms could get a larger share of a growing pie.

For years the foreign share of banking assets hovered at 3 percent. By mid-2002, due to new regulatory freedoms, their share had risen to almost 8 percent. This does not even count the failed domestic banks bought out by foreigners.

By 2001, nine major Japanese life insurers had either failed or come close to it, and then been bought out by foreign investors. Overall, with nineteen of Japan's forty-two life insurers now affiliates of foreign firms, the foreigners gained a 13 percent market share by 2001, up from only 1.6% in 1997. This is important because the assets held by just the fourteen largest life insurers are equivalent to about 20 percent of the total assets held by all banks.

Changing Attitudes

Perhaps the most important progress is in the battle of ideas. For decades, most Japanese in both the elite and the public resisted competing imports and inward FDI. They considered them an impingement on both job creation and the ability of Japan to control its own destiny. Now, many reformers clearly regard FDI as an ally, and to a lesser extent some even see the benefits of competing imports. The Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry has established an "FDI Initiative." While METI may not be as aggressive as some foreigners would like, their efforts are not simply pubic relations, as in the past. It's a major step forward. Similarly, when many farmers and apparel makers began urging open protectionism against low-cost imports from China in 2001, METI openly opposed the farm protectionism and refused to endorse the apparel protectionism. Moreover, retailers, and even some more efficient apparel manufacturers, openly opposed the protectionists. This is a new and welcome development.

Japan has a long way to go, but at least on some fronts, we can see some signs of progress.

Richard Katz is the Senior Editor of The Oriental Economist Report, a monthly newsletter on Japan (orientaleconomist.com). This article is adapted from his new book, Japanese Phoenix: The Long Road to Economic Revival (M.E. Sharpe, 2002).