India and China Take Different Roads to World Leadership – Part I

India and China Take Different Roads to World Leadership – Part I

NEW DELHI: Not so long ago India only evoked poverty and mysticism. Now the country’s name is invoked as a kind of poster child of globalization whose fast growth makes it a world leader. If the earlier view was oversimplified, so is the current one.

The latest phase of globalization has certainly propelled India forward, but the nation is still far from assuming world responsibility that its economic advance seems to suggest. For all its progress, India remains a “premature power.”

Despite status as a poster-child of globalization, India is not a newcomer to the world scene. Always a crossroads culture, India has had a long history of global engagement. Throughout history it has influenced and in turn been influenced by other cultures. Its geographical position placed it at the intersection point of both major land and sea routes, whether it was the ancient Silk Road of caravans or trading ships following the monsoons both east and the west of the Indian Peninsula.

Not surprisingly, the average Indian considers engagement with the world a familiar activity. Indians are comfortable with other cultures and remarkably adaptable to different environments. Therefore, talking about India and the world should not imply that India’s interaction with the world, its embrace of globalization, is a departure from its history. Quite the contrary, India’s reintegration into the global economy is more the reassertion of a normal historical trend, not a departure.

Of course, contemporary globalization differs from historical versions. It is certainly larger in scope and geographical spread. It is more extensive and intensive. Between 1980 and 2002, it’s estimated that global trade volume tripled while global GDP doubled. Today global trade represents 35 percent of global GDP. In the decade between 1998 and 2008, global capital flows increased from about 5 percent of global GDP to nearly 17 percent. Therefore, India deals with a world far more interconnected and interdependent than ever before.

This has brought unprecedented prosperity but also many new challenges in its wake, including the erosion of traditional concepts of national sovereignty and territory-based state authority. Therefore, while India possesses the right genes to manage globalization, it must deal with a contemporary version unprecedented in scope and diversity of the challenges.

The current international landscape offer some clues to future trends: First, the world is no longer dominated by just one predominant power and an ascendant alliance headed by it. Now there is a cluster of major powers. The US remains, by far, the preeminent power and the ascendancy of the West continues. However, there has been, for some time, a trend towards the diffusion of economic power as well as political influence, steadily changing relative weights of different powers. Over the past two decades, in particular, the center of gravity of global economic power has shifted towards Asia – a consequence of sustained, accelerated economic growth in China, India and others in the region as well.

Therefore, in dealing with global and cross-cutting issues, such as energy security and climate change, food and water security, maritime security, international terrorism and drug-trafficking, dealing with pandemics and other public health issues, the active participation and cooperation of major emerging economies are indispensable.

Secondly, even though asymmetries in power distribution remain, the very nature of transnational issues makes it impossible for the strongest nation in the world, or a coalition of industrialized and developed countries, such as the G-8, to find solutions to global challenges. Global regimes to address such challenges can no longer be imposed on the rest of the world by the most powerful countries. If the emerging economies can’t always prevail in shaping the global arrangement in any particular area, they certainly enjoy the negative power to prevent such arrangements being imposed. This has been apparent at the stalled Doha trade round where collective opposition of the Group of 20 in which countries like India and Brazil played a key part in resisting pressure by developed nations to liberalize. It was in evidence at the Copenhagen Climate Conference, where again concerted opposition by developing countries blocked the European Union–led push to transfer burden of climate mitigation on poor nations. This may create the impression that emerging countries have been obstructive in international negotiations. Quite the contrary, they are now more effective in safeguarding their own perceived interests.

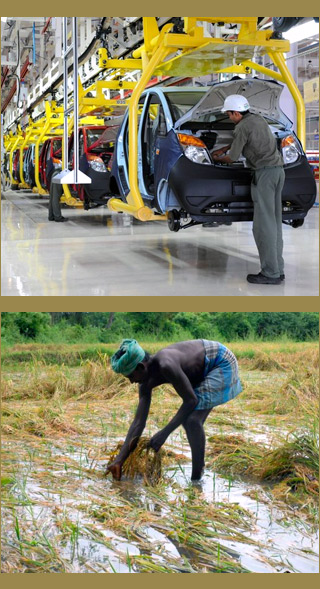

The interests of premature powers, like India, differ from those of established powers. The hallmark of a “premature power” is that in overall GDP terms, in terms of share of global trade and investment and even absolute size of its professional and technical labor force, a country may have a large global footprint.

Nevertheless, in terms of domestic economic and social indices, it remains a developing country: Per capita income would be a fraction of a mature developed country and, though the country appears rich, it confronts major challenges of poverty, illiteracy, malnutrition and disease. This pattern of development differs from that of established industrial economies, where an increase in their share of the global cake went hand in hand with the steady improvement of individual and social welfare. Therefore, in playing a global role, emerging economies face an acute dichotomy – on one hand they are expected to take on greater responsibility and make a larger contribution to the management of what are called the “global commons.”

But at the same time, they continue to seek a global regime that can deliver the resources and instruments to tackle significant domestic challenges. Indian leaders confront this tension all the time. Finding the right balance between the demands of a global role and the imperatives of domestic challenges is never easy, but must be sought in every case.

One of India’s foreign-policy objectives has been to demand a place in decision-making councils of the world. The claim to a permanent seat on the UN Security Council or G-20 membership represents this aspect of India’s worldview. But there is the constant reminder – much of the influence wielded is because India can lead, shaping the attitudes and positions of a larger constituency of the developing countries. And of course, in terms of development challenges, India’s situation is not so different from countries emerging less quickly: India wishes to sit at the so-called “high table,” then misses the umbilical chord still connecting it to the constituency of the developing world.

India is drawn back into both conduct and rhetoric that the affluent find anachronistic. Grow up, they say; don’t forget you're in a different league. In some ways, yes; in other ways, no.

This dichotomy will confront India for several years to come. On each item of the global agenda, India must seek an item-specific balance, where its role as a global actor does not undermine its ability to deliver the basic development needs of millions of its citizens. The balance it seeks must of necessity remain relevant to their interests. Otherwise, India will not sustain its global role.

Shyam Saran is the former foreign secretary of India.