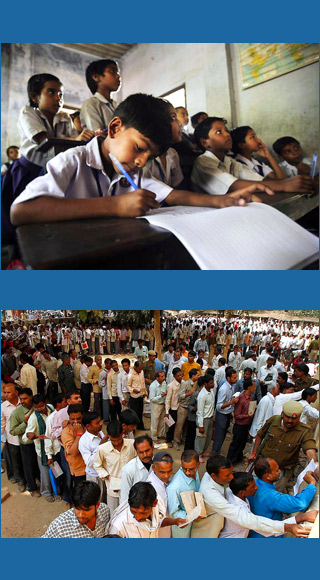

India’s Broken Schools, Cloudy Future

India’s Broken Schools, Cloudy Future

WASHINGTON: Although slowing growth and a spate of corruption scandals have taken some of the shine off India recently, the country remains widely seen as a rising power. An element of its proclaimed rise is what economists call the demographic dividend: Given its large, young population India, the argument goes, will boast a large working age population supporting relatively few retirees. That assessment is less certain, though, when one takes a closer look at the sorry state of Indian education.

According to the OECD’s Program for International Student Assessment, Indian eighth graders have math skills comparable to South Korean third graders, and Indian students ranked second to last of 75 countries surveyed in writing and mathematics, ahead of tiny, landlocked Kyrgyzstan. Though the two Indian states chosen for the survey, Tamil Nadu and Himachal Pradesh, do not represent the entire country, they are generally regarded as among the more successful in providing basic education to their children.

In a report last year, the NGO Pratham found that more than half of all fifth-grade students in India cannot read second-grade texts. What’s more, schools are getting worse: reading and math skills declined between 2010 and 2011.

The alarming state of the country’s schools has implications that extend beyond economics. Bluntly put, India cannot hope to claim a longed for seat at the head table of global affairs if it continues to get education basics wrong at home.

India’s future depends on its ability to absorb its burgeoning youth population into the workforce. The International Labor Organization estimates that over the next eight years alone India must find jobs for more than 8 million new workers each year. But despite a vast labor pool, top companies already struggle to recruit qualified workers. A recent report by staffing company TeamLease finds that nearly six in ten Indian college graduates “suffer from some degree of unemployability.” Software and services trade lobby group NASSCOM reports that only 15 percent of Indian college graduates are qualified for jobs in high-growth global industries such as call centers and technology companies. The roots of this problem lie in the failure of schools to provide an adequate education.

A large illiterate or semi-literate population will constrain India’s ability to attract new investment and knit its economy more firmly into the global supply chains that drive prosperity elsewhere in Asia.

Historically, India’s education deficit can be traced to the combination of a cash-strapped government and a focus on creating centers of excellence in higher education rather than ensuring basic literacy for all. But with economic growth swelling government coffers since the advent of liberalization in 1991, this is no longer true. Today’s system failures are instead driven by a fundamental misunderstanding of the government’s role as an education provider. Rather than analyzing what drives effective learning, India has opted to pump more money into a broken system while inventing cumbersome regulations that may end up doing more harm than good.

To be sure, more money for education is part of the solution, but not – as India’s left-leaning UPA government appears to believe – the entire solution. To begin with, the country needs to stop burdening private schools – many of which serve poor students better than government counterparts – with excessive and harmful regulations. It also needs to set benchmarks for teachers and measure success by learning outcomes rather than resource inputs. As far as possible, regulation should not interfere with the principle of providing choice. Ultimately, parents, not government bureaucrats, are best positioned to make decisions for their children.

India’s education woes can be traced back to independence from the British. At the time, in contrast to most developing countries, India emphasized tertiary rather than primary education. This enabled India to develop a few excellent universities such as the Indian Institutes of Technology (IITs) and Indian Institutes of Management (IIMs), and to churn out highly skilled engineers and PhDs. At the same time, however, primary schools were short-changed of resources. Over time, teacher and student absenteeism in government schools became rampant, accountability at the local level all but vanished, and rigid teaching methods failed to encourage students to develop problem-solving skills. By 2001, India’s literacy rate of 61 percent lagged most of its peers in East Asia.

In response to these failings, private schools serving students of all income levels sprang up across India. By 2005, nearly one in five students attended a private school. Recognizing the crisis in public education, the government has more than doubled federal expenditures on education from about $4.2 billion in 2005 to an allotted $10 billion in 2012. Meanwhile, in 2009 it rolled out an expansive Right to Education Act ostensibly meant to give every Indian child a quality education.

Ironically, RTE may end up doing more harm than good. Onerous infrastructure requirements focus schools’ attention disproportionately on resource inputs like boundary walls and outdoor playgrounds rather than teaching. Though meant to weed out fly-by-night operators, this also ends up penalizing good private schools that cater to the poorest Indians. Many cannot will not be able to afford the new requirements. In a nutshell, private schools serving the poor with committed teachers but poor infrastructure will be shuttered while inefficient government counterparts garner more resources without improving learning outcomes.

What India needs, argues Harvard University’s Lant Pritchett, is to “hire teachers who want to teach and let them teach,” mixing autonomy with “accountability for results – not just narrowly measured through test scores, but broadly for the quality of the education they provide.”

RTE also decreases accountability for learning by decreeing that students can’t fail and scrapping a national examination for tenth- grade students. All in all, it has cemented the central government’s rigid control over India’s vast and diverse education system. By demanding that private schools impose a 25 percent quota for poor students – a clause that a consortium of elite private schools failed to overturn in the Supreme Court – RTE’s new regulations may also drown India’s few centers of educational excellence in a sea of mediocrity. Schools are not allowed to test to determine admissions.

Finally, RTE focuses too much on enrollment rates. But India’s 96.7 percent enrollment rate conceals persistent teacher and student absenteeism. Pratham estimates that teachers are in the classroom less than 80 percent of required hours, and students attend about half the time. RTE does not address this. With no opportunities for students to repeat classes they have not mastered and no national learning assessment, the early warning signs that student learning is declining is unsurprising.

Rather than erecting roadblocks for private schools, the Indian government ought to leave them alone and focus on making government schools more competitive by attracting top-quality teachers and rewarding effective teaching and improved student performance. This will require providing teachers with opportunities for professional advancement by monitoring student performance, then rewarding effective teachers and firing inept ones.

To sustain its economic rise, India needs a globally competitive workforce. The process of developing one starts in primary school, but the government’s heavy-handed approach to education is ineffective. India must change its approach or risk impairing its future growth and jeopardizing its place in the global economy.

Julissa Milligan is a research assistant at the American Enterprise Institute in Washington, DC. Sadanand Dhume is a resident fellow at AEI. Follow him on Twitter @dhume01. The authors will field readers’ questions for a week after the publication date.