India’s Modi Turns the Tables on China

India’s Modi Turns the Tables on China

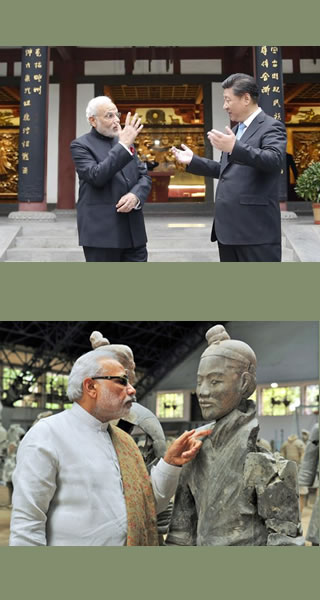

LONDON: The three-day trip to China by Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi was rich in symbolism and atmospherics, but did little to remove the basic distrust tied to decades-long border dispute and mutual suspicion about their strategic objectives. Candid talk by Modi not only suggested that, despite growing economic cooperation India remained wary of China and would carry on his policy of balancing the Chinese threat by building close ties with other powers. In a pointed allusion to the reason behind India cultivating relations with the US, Japan or Australia, Modi stressed the need to “ensure that our relationships with other countries do not become a source of concern for each other.”

India’s engagement with China has become circumscribed by intractable boundary disputes.

During Modi’s visit, a number of agreements were signed including on outer space, civil nuclear cooperation, skill development, expanding educational exchange, a new leaders’ forum at the provincial level among others. The two militaries also decided to operationalize the hotline between their two headquarters as well as increasing the number of border meeting points for their military personnel to maintain peace on the border. India also decided to grant electronic visas to Chinese visitors to India.

Despite the anodyne nature of these pacts, the relationship has shifted: Modi’s visit to China will be remembered for his plain-speaking, by no means an insignificant achievement. For years, Indian political leaders had traveled to China and said what the Chinese wanted to hear. Modi changed all that when he openly “stressed the need for China to reconsider its approach on some of the issues that hold us back from realizing full potential of our partnership” and “suggested that China should take a strategic and long-term view of our relations.”

The joint statement issued during Modi’s visit was circumspect, focusing on “the imperative of forging strategic trust.” In his speech at Tsinghua University too, Modi went beyond the rhetorical flourishes of Sino-Indian cooperation, pointing out the need to resolve the border dispute and to “ensure that our relationships with other countries do not become a source of concern for each other.” This is a shift in Indian traditional defensiveness vis-à-vis China, underscoring a recalibration in policy by squarely putting the blame for stalemate in bilateral ties on China’s doorsteps.

For all the hype about hosting Modi, China refused to yield on border issues. It refused to cease issuing stapled visas – attaching a piece of paper with a visa stamp rather than directly stamping the passport – to Indians from Arunachal Pradesh and Jammu and Kashmir traveling to China. The implication is that China refuses to acknowledge India’s sovereignty over those areas.

China resists moving forward on clarifying the Line of Actual Control – a boundary between Chinese and Indian land in the Himalayas. China maintains that the border dispute is confined to 2,000 kilometers, largely in Arunachal Pradesh, whereas for India the dispute spans more than 4,000 kilometers, including the Aksai Chin area ceded to China by Pakistan. China has bolstered its ties with Pakistan in recent weeks by promising $46 billion investment package in the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor, between Pakistan’s Gwadar Port on the Arabian Sea and China’s western Xinjiang province, as part of Beijing’s ambitious Maritime Silk Road Initiative, and this corridor will traverse through disputed territory in Kashmir, land occupied by Pakistan but claimed by India.

The Modi government, with its decisive mandate, is better positioned than its predecessors to deliver on tough foreign policy decisions, yet Beijing decided against taking risks. Instead, China has given space to Modi to follow a two-pronged approach: reaching out to China on economic and cultural issues and drawing red-lines on security matters, continuing to seek out new partners as well as military and diplomatic means to protect territory.

Modi is seeking to broaden the basis of engagement with China. During his visit, Modi reached out to the Chinese investors, asking them to take advantage of the “winds of change” in India with its more transparent regulatory regime. He views investments from China essential if the India growth story is to be fully realized. China promised to invest over $20 billion in India over the next five years, and other pacts signed during Modi’s visit are likely to yield $10 billion worth of Chinese projects in renewable energy, the financial sector, education, railways and ports.

Though India has decided to become a founding member of the China-led Asian Infrastructure Investment Bank, the limits to Sino-Indian economic cooperation are underscored by India’s reluctance to join China’s Maritime Silk Road Initiative and joint scouring of the Indian Ocean seabed for resources as proposed by China. Chinese businesses complain of Indian red-tape, largely a function of the bureaucracy’s wariness about an overdependence on China and of espionage. India’s corporate sector has failed to gain market access in China in their core competencies such as pharmaceuticals, IT and agriculture. As a consequence, the trade deficit continues to widen in China’s favour.

Indian and Chinese leaders have discussed civilizational ties for decades, but Modi is the first prime minister who engages with China on the basis of a shared cultural heritage. By emphasizing Buddhism, Modi is keen to build cultural ties involving ordinary Indians and Chinese. The decision to grant electronic visas to Chinese visitors is aimed at enhancing mutual trust with a fillip to people-to-people contacts.

This implies a new sense of purpose in India’s China policy, which has for decades focused on downplaying differences and exaggerating convergence. Starting with his inauguration, Modi invited the Tibetan government in exile to his inauguration and spoke openly of Chinese expansionism. After decades of neglect, there are signs that the Modi government is pursuing a time-bound program of infrastructure buildup in border areas. More troops are being deployed with better weaponry and support technology. Projects include six advanced landing grounds for military aircrafts, strategic railway lines, tunnels and arterial roads leading up to the Line of Actual Control.

Modi is confident of India’s ability to emerge as a significant global player, allowing him to leverage ties with China and the United States to secure Indian interests. He has followed a dynamic foreign policy, developing closer ties with the US and strengthening military cooperation with Australia, Japan and Vietnam while working to regain strategic space in the Indian Ocean region. Modi’s visits to Mongolia and South Korea after China signal that New Delhi remains keen on expanding its profile in China’s periphery. To counter Chinese presence in the Gwadar port in Pakistan, which many in India view as a potential Chinese naval hub, India is building a port in Iran’s Chabahar to gain access to Afghanistan. India has given a green light for collaborating with the US on construction of its largest warship, the 65,000-ton aircraft carrier INS Vishal.

For years, Delhi was labeled as the obstacle to normalizing Sino-Indian ties. Modi has deftly turned the tables on Beijing by signaling that he is willing to go all out in enhancing cultural and economic ties. The onus of reducing strategic distrust rests with Beijing – success or failure of the Asian century might depend on Beijing’s response.

Harsh V. Pant is professor of international relations at King's College London and the author of India's Afghan Muddle (HarperCollins).