India’s Search for a Foreign Policy

India’s Search for a Foreign Policy

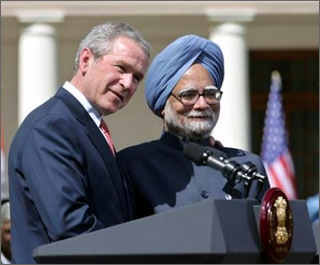

above, President Bush and Prime Minister Singh commit to the pact in 2006

LONDON: India has at various times been described as a rising giant, a superpower and by Indian leaders themselves as a “bridging power,” but a closer look at the shambles that pass for India’s foreign policy dispels such notions.

Take a look at the fate of the US-India civilian nuclear-energy pact. With time running out for implementing the pact, the Indian political establishment is in turmoil. The attempt to present a face of unity on the issue continues even though the vast gulf separating various political groupings has been clear for some time: The Communist allies of the ruling coalition have long made it known that they will not allow a US-India rapprochement to take place and were willing to let the government fall if it tried to go ahead. They have yet to forgive the US for winning the Cold War. The opposition Hindu nationalist Bharatiya Janata Party is worried that its opponent will take credit away from its own nuclear legacy with this deal and insists that the true role of an opposition party is to oppose the party in power even if it goes against the grain of what the BJP has long stood for. The coalition leader Congress Party meanwhile continues to muddle along, desperately trying to cling to power for a few more months and postponing a final decision for as long as possible.

As one surveys the landscape of Indian foreign and security policy today, it appears strewn with wreckage on all sides. The Chinese have upped the ante on the border dispute, the terrorists are attacking the country with utmost impunity, the morale of Indian defense forces is at an all time low, the Maoists are gaining ground in large parts of the nation, the peace process with Pakistan is going nowhere, and the US-India nuclear deal is stuck with no resolution in sight. There’s a whiff of fragility and underconfidence in the air, as if at any moment the entire façade of India as a rising power might simply blink out like a bad idea. The absolute control of the Communists on all realms of policymaking, the single point agenda of the Congress Party to stay in power as long as possible and the insistence of the BJP upon destroying its own credibility as a national party – all have ensured that the Indian foreign policy continues to drift without direction.

The seemingly never-ending debate on the US-India nuclear deal has made it clear that today Indian policy stands divided on fundamental foreign policy choices facing the nation. What Walter Lipmann wrote for US foreign policy in 1943 applies equally to the Indian landscape of today. He had warned that the divisive partisanship that prevents the finding of a settled and generally accepted foreign policy is a grave threat to the nation. “For when a people is divided within itself about the conduct of its foreign relations, it is unable to agree on the determination of its true interest. It is unable to prepare adequately for war or to safeguard successfully its peace.” In the absence of a coherent national grand strategy, India is in the danger of losing its ability to safeguard its long-term peace and prosperity.

As India’s weight has grown in the international system in recent years, there’s a perception that India is on the cusp of achieving “great power” status. It is repeated ad nauseum in the Indian and often in global media, and India is already being asked to behave like a great power. There is just one problem: Indian policymakers themselves are not clear as to what this status of a great power entails. Bismarck famously remarked that political judgment was the ability to hear, before anyone else, the distant hoofbeats of the horse of history. In India’s case, everyone but the Indian policymakers it seems hears the hoofbeats of that horse. Indian policymakers seem to believe that, just because their nation is experiencing robust economic growth, they don’t really need a serious foreign policy and that ad hoc responses are enough. There’s an intellectual vacuum at the heart of Indian foreign policy that has allowed India’s engagement with the rest of the world to drift and the result is that as the world is looking to India to shape the emerging international order, India has little to offer except some platitudinous rhetoric, which only shows the hollowness of India’s rising global stature. However much Indians like to be argumentative, a major power’s foreign policy cannot be effective in the absence of a guiding framework of underlying principles that is a function of both the nation’s geopolitical requirements and its values.

Indian foreign-policy elite remains mired in the exigencies of day-to-day pressures emanating from the immediate challenges at hand rather than evolving a grand strategy that integrates the nation’s multiple policy strands into a cohesive whole that can preserve and enhance Indian interests in a rapidly changing global environment. Assertions, therefore, that India does not have a China policy or an Iran policy or a Pakistan policy are irrelevant. India does not have a foreign policy, period. This lack of strategic orientation in Indian foreign policy often results in a paradoxical situation where on the one hand India is accused by various domestic constituencies of angering this or that country by its actions while on the other hand India’s relationship with almost all major powers is termed as a “strategic partnership” by the Indian government. Soon it will be almost two decades since the Cold War officially ended, yet India continues to debate the relevance of the Non-Aligned Movement (NAM). Whatever the merits or otherwise of NAM, the Indian foreign-policy establishment seems content to rigidly hold on to concepts and intellectual frameworks that may have had some utility when they were developed but which have become outmoded in the present strategic context.

India is fortunate that it has encountered an incredibly benign international environment in recent years, making it possible for it to expand its bilateral ties with all the major powers simultaneously. This has given rise to some fantastic suggestions such as India being well-placed to be a “bridging power,” enjoying harmonious relations with the US, Russia, China and the EU. Such a suggestion not only implies that the major global powers are willing to be “bridged,” but also that India has the capabilities to serve as that “bridge.” Moreover, the period of stable major power relations is rapidly coming to an end. Soon difficult choices must be made and Indian policymakers should have enough self-confidence to make those decisions even when they go against their long-held predilections. But a foreign policy that lacks intellectual and strategic coherence will ensure that India forever remains poised on the threshold of great-power status, not quite ready to cross over.

India’s economic rise in the last few years presented opportunities that the nation’s decision-makers have not adequately exploited or leveraged to their nation’s advantage. It would indeed be a tragedy if history were to describe today’s Indian policymakers in the words Winston Churchill applied to those who ignored the changing strategic realities before the Second World War: “They go on in strange paradox, decided only to be undecided, resolved to be irresolute, adamant for drift, solid for fluidity, all-powerful to be impotent.” India today, more than any other time in its history, needs a view of its role in the world quite removed from the shibboleths of the past.

Harsh V. Pant is with the Defence Studies Department, King’s College London, and also an associate with the Centre for Science and Security, King’s College London. Click here to read an excerpt of his book, “Contemporary Debates in Indian Foreign and Security Policy: India Negotiates Its Rise in the International System.”