Interrupting a History of Tolerance – Part I

Interrupting a History of Tolerance – Part I

ADELAIDE: Two widely watched television series broadcast in recent years provide compelling examples of anti-Semitism in the Arab Muslim world.

In November 2002 Egyptian state television and other stations in neighboring Arab countries began broadcasting a 41-part serial called “Knight Without a Horse,” based on the notoriously anti-Semitic “Protocols of the Elders of Zion” document. One episode showed Jews meeting in a dark room decorated with symbols, discussing the establishment of a Jewish state in Palestine, arguing that Britain had an interest in establishing such a state to fracture Arab and Muslim unity.

A year later Hezbollah’s Al-Manar satellite television channel in Lebanon, with a worldwide audience of millions, broadcast 30 parts of a Syrian-produced series titled “Al-Shatat,” or “Diaspora.” The series purports to tell the story of Zionism from the beginning of the 19th century to the establishment of the state of Israel, depicting a secret global Jewish conspiracy. The series accused Jews of bringing death and destruction upon humanity, unleashing both world wars, discovering chemical weapons, and destroying Hiroshima and Nagasaki with nuclear weapons.

Intriguingly, there is little evidence of deep-rooted anti-Semitism in the classical Islamic world. According to one leading Western scholar of Islamic history, Bernard Lewis, in contrast to Christian anti-Semitism, Muslim attitudes toward Jews historically did not include hate or fear, but rather a contempt expressed toward all non-believers. Unlike many European philosophers of the Enlightenment era who at one time or another gave vent to anti-Semitism, nothing comparable can be found in the writings of great philosophers of classical Islam.

Lewis attributes the absence of anti-Semitism in Islamic tradition to the rejection of deicide. In Islam, the Gospels have no place in education, and Muslim children are not brought up on stories of Jewish deicide. Indeed, the Koran rejects the notion of deicide as “blasphemous absurdity.”

After reviewing the history of Jewish-Muslim relations in his book “Semites and Anti-Semites,” Lewis concludes that, in general, Jewish and Muslim theology are far closer to each other than either is to Christianity. Jews lived under Islamic rule for 14 centuries and in many lands. Jews were never free from discrimination, but were rarely subjected to persecution as they were in Christendom. There were no fears of Jewish conspiracy and domination, no charges of diabolic evil.

Yet in modern times, Prophet Mohammad’s conflict with the Jews has been portrayed as a central theme in his career, their enmity given cosmic significance.

Al-Manar television bills itself as the global voice of Islamism. Popular among millions of its viewers for countless video clips that use stirring graphics and uplifting music to promote suicide bombing, the satellite channel not only pushes for terrorist acts against Israel but inspires, justifies and acclaims them.

In general, the Arab media dismiss Western accusations that programs like “Al-Shatat” and “A Knight Without a Horse” are vehicles of anti-Semitism. Most Arab leaders and intellectuals claim that such accusations are merely an attempt by the “Zionist lobby” in the US and Jewish organizations in Europe to silence legitimate criticism of Israel.

Analysts regard Hamas and Al Qaeda, besides Hezbollah, as the most anti-Jewish Islamist groups. The Hamas Charter of Allah is grounded in the superiority of Islamic ideological tradition and regards capitalism, communism, the West, Zionism and Jewry as components of a multifaceted onslaught, acting in concert to destroy Islam and eliminate the Palestinian people from their homeland. The charter advocates the establishment of an Islamic state and approvingly cites the “Protocols of the Elders of Zion,” holding the Zionist movement and Jews in general responsible for every real or perceived ill that afflicts the modern world. Anti-Semitic rhetoric is a significant part of Al Qaeda’s ideology, with Jews labelled as eternal enemies of Islam.

The penetration of modern-style anti-Semitism into the Islamic movements can be traced back to the Christian Arab minorities that had close contacts with the West in the 19th century. European emissaries actively encouraged anti-Semitism, and Christian minorities had practical reasons to oppose Jews as their main economic competitors.

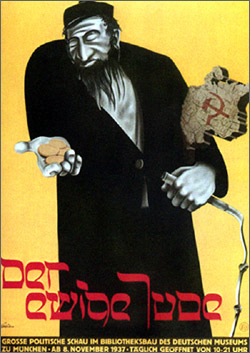

Translation by Christian Arabs of European anti-Semitic writings compounded the anti-Semitism. One example was the Arabic translation of a lengthy French book by Georges Corneilhan, first published in Paris in 1889, about the Jews in Egypt and Syria. Portraying the French anti-Semitic literature of the times, the book denounced the Jews as the source of corruption destroying France and the world. Another book, from Christian author Habib Faris was “Surakh al-Bari fi Buq al-Hurriyya,” or “The Call of the Innocent With the Trumpet of Freedom.” The compilation of anti-Semitic myths, largely of European origin, accuse Jews of ritual sacrifice like the one depicted in the Al-Manar series, ascribing this to Talmudic teachings.

The Ottoman Empire did not approve of early attempts to spread anti-Semitism, and from time to time, Ottoman authorities closed newspapers involved in anti-Jewish incitement as a threat to public order.

In the mid-20th century, German propaganda took over exploiting anti-Jewish sentiments in the Middle East. Seth Arsenian, a former British intelligence officer turned academic, reports that from 1938 until the end of the war, the radio station located at Zeesen near Berlin dominated the Arab scene, utilizing the services of well-known Arab exiles and academics in Germany.

A major theme of the radio broadcasts was that the Allies were motivated by “greedy imperialism,” bound to “rob the Arab of his wealth and enslave him forever.” Broadcasts described the Allies as “Jewish controlled” and “United Jewish nation,” portraying Allied leaders as “untrustworthy, perfidious, and decadent individuals,” and German leaders as sympathetic to Arab Muslim aspirations.

Relentlessly anti-Semitic propaganda insisted that the Jews were tools of British imperialism, bent on expelling the Palestinians from their homeland, creating a Jewish state in Palestine and controlling the whole of the Middle East and its oil. The station extolled Arab culture, and a major aim of the propaganda was to create disturbances and encourage armed rebellion in the Arab world against the British.

Matthias Kuntzel, a German political scientist, agrees with Lewis that anti-Semitism based on the notion of Jewish world conspiracy is not rooted in Islamic tradition, but in European ideological models. In a paper published in 2005 in The Jewish Political Studies Review, building on the work of Arsenian, Kuntzel suggests that the decisive transfer of anti-Semitic ideology to the Muslim Arab world took place between 1937 and 1945 via Nazi propaganda.

According to Kuntzel, Islamism is an independent anti-Semitic and anti-modern ideology. Yet the German National Socialist government supported Hajj Amin el-Husseini, the Mufti of Jerusalem, the Islamic Brotherhood and the Palestinian Qassamites in translating the European anti-Semitism into an Islamic context.

In 1931 radical Islamist Imam Izz al Din Al-Qassam set up a Salafi movement in Haifa that advocated return to the original Islam of the 7th century with a practice of militant jihad against the infidels. He was killed in a military encounter and Hamas’s suicide-bombing unit bears his name.

Following the recommendation of the British Peel Commission in 1937 for the partition of Palestine, the Muslim Brotherhood of Egypt, active in the Palestinian resistance movement against the increasing flow of Jewish immigration from Europe to Palestine, also joined the anti-Jewish agitation and received financial and ideological support from German government agencies.

Kuntzel maintains that the Zeesen transmitter transferred the anti-Semitic ideology to the Arab world, linking early Islamism with German National Socialism. Although radio Zeesen ceased operation in April 1945, its frequencies of hate continued to reverberate into the Arab World.

Riaz Hassan is Australian Professorial Fellow and Emeritus Professor at Flinders University, Adelaide, Australia. His latest book, “Inside Muslim Minds: Understanding Islamic Consciousness,” will be published later this year.