Iran’s Nuclear Program: Handle With Care

Iran’s Nuclear Program: Handle With Care

BLOOMINGTON: Addressing reporters at the Fifth Democracy Forum in Bali just two days after the US presidential elections, Mahmoud Ahmadinejad observed that “Iran's nuclear program has been politicized and the dispute should be resolved by direct talks between Iran and the United States.” The Iranian president’s remarks were headlined by the Islamic Republic News Agency.

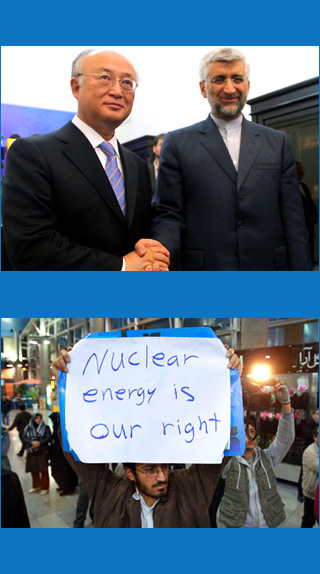

Ahmadinejad steps down in early August 2013; striking a deal that removes both economic sanctions and military threats would ensure a banner exit. Indeed, a new round of talks with the International Atomic Energy Agency is scheduled in Tehran for mid-December. Yet once again Ahmadinejad could lack sufficient domestic clout and international trust to cement a deal. Nor is there consensus among his opponents on how tensions with the West should be handled, even though parliamentarians, the president and Supreme Leader Ayatollah Ali Khamenei would all have to sign off on any deal.

The Islamic Republic has been subjected to political infighting since its inception in 1979. Ahmadinejad’s two terms in executive office have been some of the most turbulent of times. First came a populist uprising against his reelection in June 2009. Next, clerical supporters largely left his side in the wake of a presidential power grab where Ahmadinejad characterized Iran’s theocratic system of governance, or velayat-e faqih, as ineffective and needing evisceration.

Opponents in the legislative and judicial branches of the Iranian government – headed by two brothers, Parliamentary Speaker Ali Larijani and Chief Justice Sadegh Larijani, from a well-established family of ayatollahs – have retaliated by torpedoing Ahmadinejad’s negotiations with the IAEA. They also imprisoned several of Ahmadinejad’s aides on charges of corruption and of insubordination toward Khamenei. The Islamic Revolutionary Guard Corps seeks to expand its authority at the expense of the presidency and legislature. But militarization of politics has come under fire from the Iranian polity.

Moreover Ahmadinejad may not be a lame-duck chief executive for he has survived every internal challenge. When interrogated by parliamentarians in March, Ahmadinejad mocked his questioners. This time around even the president’s harshest critics like Speaker Larijani and Tehran prayer leader Ayatollah Ahmad Jannati caution against confronting the president. Indeed, temporarily setting aside his own rivalry with Ahmadinejad, former President Akbar Hashemi Rafsanjani, whose son and daughter are now in Tehran’s Evin Prison on charges of fomenting rebellion, has echoed the call for direct negotiations and a resumption of relations with the US.

The Iranian public appears conflicted about the nation’s nuclear program as well. A recent University of Maryland poll conducted in Iran with 1,110 respondents and a 3 percent margin of error indicates 85 percent support a civilian nuclear program while only 38 percent also support a military one. Such statistics have remained fairly steady over the past years despite tightening economic sanctions devastating Iranians’ standard of living. Surveys in July by official Iranian news agencies also suggest that over 60 percent of Iranians would accept cessation of uranium enrichment in exchange for a lifting of sanctions and reincorporation of their country into the global community. As important, less than one-fifth of respondents favored military confrontation with the US.

Not surprisingly, Iranian citizens’ desire to reach diplomatic resolutions to defuse tensions with the US specifically and the West generally has become more urgent as economic sanctions have become more expansive, better enforced and very painful. Iranians are feeling the full brunt of those sanctions: inflation has averaged 24.9 percent for the past 12 months and climbed to 32 percent recently; prices of staple foods like bread, milk, vegetables, meats and cooking oil have risen between 18 and 146 percent; housing costs are up 20 percent as are water costs; even essential medicines are in short supply Those soaring expenses led to street protests in October by desperate householders and disgruntled businessmen.

Not only must Iranian politicians deal with the growing discontent of ordinary citizens, they increasingly are hard-pressed to find resources for resolving the mounting problems. Iran’s currency, the rial, has lost over 90 percent of its value vis-à-vis the US dollar since August as crude oil and natural gas exports fell to all-time lows, constricting inflow of hard foreign currencies. In November, the parliament’s Budget Committee projected a deficit of 740 trillion rials, more than $60 billion, or 45 percent of the country’s budget. Consequently, Iran simply cannot afford a large-scale military confrontation.

Iran recommenced its nuclear program, begun by the last Shah, after experiencing the onslaught of chemical weapons of mass destruction from Saddam Hussein’s Iraq in the 1980s. Iran’s leaders realize nuclear power can provide their nation with absolute security from foreign threats. Likewise, possession of nuclear weapons vaults countries into the category of superpowers. Iranian leaders yearn for their nation’s return to global prominence, speaking of their desire to reshape the global order. Similarly, disseminating nuclear technology would yield Tehran influence among potential recipients in the developing world. It would give Iran more leverage in interactions with the US and other world powers too. Yet decision-makers in Tehran have not rushed toward nuclear might – they are inching forward with characteristically Persian caution.

In January while testifying to the US Congress, Director of National Intelligence James Clapper made a highly pertinent observation: “Iranian leaders undoubtedly consider Iran’s security, prestige, and influence, as well as the international political and security environment, when making decisions about its nuclear program.”

Indeed, Supreme Leader Khamenei, President Ahmadinejad, Speaker Ali Larijani, Chief Justice Sadegh Larijani, former President Rafsanjani, and even opposition politicians such as former President Mohammed Khatami and former Prime Minster Mir Hossein Mousavi find common ground when it comes to Iran’s security, prestige and influence. They are joined by a vast majority of other Iranians on these issues, cherishing their nation’s long, esteemed, history and civilization – one which predates that of the western societies by many centuries.

Western sanctions and threats have never deterred Tehran which claims its nuclear technology is solely for peaceful purposes as permitted by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. So perhaps it is their public’s strengthening attitude favoring concessions that has convinced Iran’s leaders to admit misleading the IAEA about past nuclear advances, to slowing the pace of enrichment, and to begin transforming high-enriched uranium into a powdered form unsuitable for use in weapons.

Yes, the US can continue its cyber-attacks, assassination and economic skirmishes with Iran and even bomb Iran’s nuclear facilities. But the Iranian government now possesses both the technological knowhow and industrial capability to rebuild its nuclear program. Toppling the ayatollahs would certainly remove the militaristic threat they pose to the world and must remain an option. But war-weary Americans do not favor a full scale conflagration with Iran, nor do Europeans, as the US, EU and Iranian administrations know well. So, for now at least, the US is sticking to the negotiations and sanctions tracks.

Yet success requires more than merely forcing Iran’s leaders to see their nation crumbling under sanctions and to fear the possibility of military actions rendering them impotent. Iranians’ sense of national pride must be accommodated by facilitating their reaching the conclusion that giving up the nuclear-weapons option does not constitute bowing to the whim of foreign powers, but reopening the path to economic prosperity. Only then will an enduring deal be reached.

Jamsheed K. Choksy is professor of Iranian Studies at Indiana University where he served as director of Middle Eastern Studies. He also is a member of the National Council on the Humanities at the US National Endowment for the Humanities. Carol E. B. Choksy is adjunct lecturer in Information Science at Indiana University. She also is CEO of IRAD Strategic Consulting, Inc. This analysis reflects their own views.