Iran’s President-Elect May Offer New Opening

Iran’s President-Elect May Offer New Opening

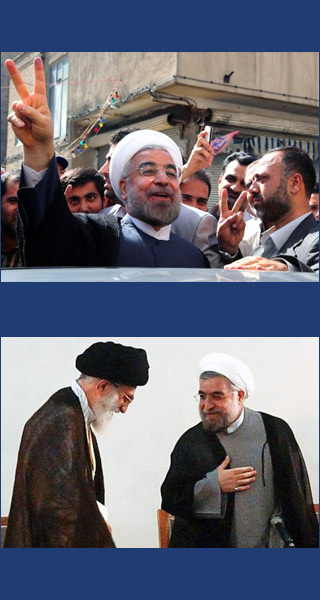

EAST LANSING: Hassan Rouhani’s election to the presidency of Iran is a tribute both to the democratic aspirations and political savvy of the Iranian people and the political acumen of Supreme Leader Khamenei and his inner circle that did not stand in the way of this outcome. By all accounts the election was free adding to the legitimacy of the Iranian political process and the president-elect’s standing.

Rouhani’s election signals a desire within Iran for a person at the helm of Iran’s day-to-day conduct of foreign policy who has the diplomatic skills to engage with the rest of the world, especially the major powers. Involved in national security affairs for 16 years, Rouhani is reported to have these skills in abundant measure.

Although not Khamenei’s preferred candidate, Rouhani does have the confidence of the supreme leader as indicated by the fact that he served as the latter’s representative on the National Security Council. This could give him greater latitude in foreign policymaking. Furthermore, Rouhani’s long stint in the Iranian National Security Council gives him the advantage of intimately knowing major players involved in the formulation of Iranian foreign policy and their views on national-security issues. It also gives him the capacity to broker policies on the basis of give and take that are acceptable to major constituencies. Unlike President Mahmoud Ahmadinejad, he can play the game of "bureaucratic politics" dexterously and perhaps prevent sabotage of policies because of infighting among regime insiders.

The most important foreign-policy issue facing Rouhani is the stalled negotiations with the P5+1 on Iran’s nuclear-enrichment program – of particular concern because Iran’s economy has become hostage to this issue. Severe economic sanctions have hurt the economy greatly with inflation officially at 31.5 percent, but higher in actual fact. Sanctions imposed on foreign banks doing business with the country have reduced Iran’s ability to market its oil and gas thus creating a major financial crisis.

Some commentators have noted that since Rouhani was Iran’s chief nuclear negotiator between 2003 and 2005 when Iran had agreed to temporarily suspend uranium enrichment to create an atmosphere of trust between the European powers and Tehran, there is a possibility that he may do so again to help negotiations proceed. However, Rouhani rejected this option in his first press conference as president-elect: “ We are now in a different situation… All should know that the next government will not budge from defending our inalienable rights [on uranium enrichment].”

This statement suggests that there are certain red lines that Rouhani will not cross on the nuclear issue because of national consensus on the subject. Furthermore, Iran has reached a point in its effort to enrich uranium that puts it within striking distance of mastering the nuclear fuel cycle – the hallmark of nuclear independence in a world where great power is defined in terms of nuclear capability. Finally, Tehran finds its strategic environment menacing with two hostile nuclear weapons powers – Israel and the United States –and thus cannot afford to give up its weapons option without adequate quid pro quo, both strategically and economically.

Israel possesses a formidable nuclear arsenal and sophisticated delivery systems that make it the sole nuclear-weapons power in the Middle East. Israel has consistently implied that its security situation requires a monopoly over nuclear-weapons capability in the Middle East. It has so far assured this outcome by bombing Iraqi and Syrian nuclear facilities and threatening to bomb Iranian facilities as well. Given Israel’s nuclear capability and conventional military might, Iran perceives a credible military threat emanating from Israel especially since relations between Israel and Iran have been hostile for most of the period following the 1979 Iranian Revolution. It’s clear that Iran cannot seriously contemplate giving up its nuclear enrichment program, an integral part of keeping its weapons option open, except within the framework of a Middle East Nuclear Weapons Free Zone that includes both Israel and Iran.

The second, and more important, motive for Iran’s search for nuclear capability is the hostile relationship between the United States and the Islamic Republic of Iran. Iran finds the massive deployment of US conventional and non-conventional military power in the Persian Gulf and the Arabian Sea with land bases in the Arab littoral of the Gulf threatening, especially in the context of the US invasions of Iraq in 2003 and Afghanistan in 2001. Iran does not want to become another Iraq or Libya by giving up its nuclear option even if it continues to be rudimentary, opaque and shrouded in ambiguity.

Most analysts make the mistake of confusing cause with effect in their treatment of Iran’s nuclear policy and Iranian-US relations. Iranian nuclear aspirations are not the cause of hostile relations with the United States. Rather, hostile relations with the United States have led Tehran to increasingly commit itself to safeguard its nuclear-weapons option.

In his first press conference, Rouhani declared that he wants to reduce tensions with the United States, terming the animosity between the two sides “an old wound that must be treated” before relations can be normalized. He thus signaled that Iranian-US tensions go beyond the nuclear issue which is merely a symptom of the mistrust and antagonism bedeviling relations and that there is need for a comprehensive dialogue on this issue that goes beyond the P5+1 negotiations with Iran on the nuclear issue.

With this in mind, Rouhani, given his past record as Iran’s nuclear negotiator, will probably be willing to introduce greater transparency regarding the Iranian nuclear program and may even permit the International Atomic Energy Agency access to the Parchin military site near Tehran under certain conditions.

However, this by itself is unlikely to resolve the underlying issues causing tensions between the two nations. These issues cannot be resolved until a comprehensive strategic dialogue is instituted between the United States and Iran. Washington should seriously consider taking the opportunity presented by a more reasonable president in Iran to begin a bilateral dialogue that goes beyond the nuclear-enrichment issue and deals with, among other matters, Iran’s role as a pivotal power in the Persian Gulf and the broader Middle East.

Rouhani’s room for maneuver on issues vital to Iranian national security will be limited. A similar situation prevails in the realm of Iran’s regional policies. Tehran considers a friendly government in Baghdad essential for its national security and, therefore, will not withdraw support from Nour al-Maliki even if it may not approve of some of his ultra-sectarian policies that hurt Iran’s long-term interests.

Iran considers its support for the Assad regime in Syria non-negotiable at least in the short term. Syria, under the Assads, has been Iran’s staunchest ally going back to the dark days of the Iran-Iraq war when major powers – global and regional – lined up behind Iraq. It’s also the conduit for Iranian military and financial assistance to Hezbollah, itself one of Iran’s prized strategic assets vis-à-vis Israel, especially in the context of the latter’s threat of bombing Iran’s nuclear facilities. Above all, Syria provides Iran a foothold in the Arab world that can be used to counter what Tehran considers Saudi and American machinations against its strategic interests in the region.

Rouhani’s conciliatory diplomatic style may bring down the regional political temperature a notch, but is unlikely to change the substance of Iran’s regional policies dictated by its national interests that transcend regime concerns and personality traits.

Mohammed Ayoob is University Distinguished Professor of International Relations Emeritus, Michigan State University, and adjunct scholar, Institute for Social Policy and Understanding. His edited volume Assessing the War on Terror will be published later this year, and his book Will the Middle East Implode? is scheduled for publication in early 2014.