Iran’s Secret Quest for the Bomb

Iran's Secret Quest for the Bomb

As the Bush Administration took office in January 2001, Iran presented a classic nuclear proliferation challenge that appeared to be manageable with traditional nonproliferation tools. Today, however, the US believes the challenge is far more serious than previously thought, and that the tools for addressing it are no longer sufficient. At the upcoming June meeting of the UN's International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), Washington wants the agency to declare Iran in material breach of its non-proliferation obligations. The Bush administration fears that the development of an Iranian bomb - a project which now appears to have been bolstered by clandestine foreign assistance - could have far-reaching consequences.

For the past decade, Iran has been trying to complete a nuclear power reactor at Bushehr, begun with German assistance during the time of the Shah. Germany froze further cooperation after the 1979 Iranian Revolution. After a period of opposing all programs symbolizing modernization, Iran's Islamic revolutionary leaders signed an agreement with Russia to complete the facility. Tehran has never offered a convincing justification for why it needs the facility, given the fact that it could much more quickly and cheaply use its natural gas resources (much of it flared off) to fuel any needed electricity production. U.S. observers have seen it as a cover to permit the development of more sensitive nuclear facilities that could support a nuclear weapons program.

In early 2001, it was assumed that Iran was seeking to acquire nuclear arms, but there was little evidence that it was progressing. Washington had succeeded in persuading Russia to hold up the export of lasers that might have been usable for enriching uranium from its natural state to weapons-grade. (It takes about 25 kg of enriched uranium to make a Hiroshima style bomb.) While the Bush Administration, like its predecessor, believed Iran was pursuing other options to develop the bomb, there was also little evidence that it was succeeding. Since 1991, when Iraq was found to have clandestinely developed nulcear facilities despite its adherence to the Non-Proliferation Treaty (NPT), the UN's International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA) asserted the right to demand a special inspection of a suspect undeclared site in an NPT-party state. In 2001, it appeared that this reinforced international inspection system could be used to keep Iran on the defensive. At the first indication from U.S. intelligence that Iran was building a clandestine nuclear facility, the IAEA could demand a look, and international pressure would build for Iran to halt the apparent violation of its nonproliferation pledges.

Export controls by industrialized nations were a second arrow in the quiver of nonproliferation tools. As the result of concerted U.S. diplomacy in the 1980s, China had ceased nuclear cooperation with Iran, a nuclear embargo by Western nuclear suppliers was holding firm, and, through constant U.S. intervention, it was hoped that leakage of sensitive nuclear technology from Russia could be halted.

By the end of 2002, this hopeful view of the international nonproliferation regime was dashed by the discovery that in the previous 18-24 months, despite the vigilance of U.S. and other intelligence services, Iran had secretly made considerable progress on two different routes to nuclear weapons.

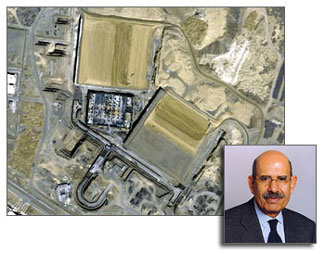

First, it had completed a pilot-scale facility to enrich uranium at Natanz using high-speed centrifuges, a demanding technology but one that is now spreading rapidly. If enlarged, the facility would be capable of producing large quantities of uranium enriched to the level needed for nuclear weapons of the type used against Hiroshima. Second, Iran appeared to have completed, or to be near completing, a facility at Arak for the production of heavy water, a product used in reactors designed to produce plutonium. This was the material used in the Nagasaki bomb.

The advanced state of these facilities was doubly disturbing because it implied that Iran possessed still other, as yet undeclared nuclear plants. When the IAEA's Director-General, Mohammed El Baradei, eventually requested and was granted a visit to the Natanz facility, his team concluded that the facility was so sophisticated that it could only have been built after Iran had constructed and operated a smaller scale, experimental enrichment unit. While Iran might claim that it had no obligation to declare the Natanz plant because it had not yet introduced natural uranium into the facility, it would have had to take this step to test out the smaller experimental facility - a clear violation of its inspection obligations under the NPT.

Moreover, the fact that Iran was attempting to produce heavy water implied that it was constructing - or had completed - a heavy-water-using reactor, which it had also not declared. (Heavy water is not needed for the nuclear power plant that Russia is building for Iran, at Bushehr.)

Thus, far from keeping Iran off balance and on the defensive, IAEA monitoring had apparently missed at least two, and possibly four, sensitive installations.

Export controls, obviously, had proven no more effective. It is highly unlikely that Iran developed uranium enrichment centrifuge technology on its own, although who may have assisted Iran to obtain it remains unclear. North Korea is one possibility. It is believed to have traded medium-range No-Dong missiles to Pakistan in return for centrifuge enrichment know-how and, possibly, centrifuge prototypes. At the time, North Korea was also selling the No-Dong to Iran, for cash. It is not unreasonable to imagine Pyongyang struck a second bargain with Tehran to sell it Pakistani-origin enrichment technology.

It is also possible that Pakistan might have made the sale directly. Elements of Pakistan's leadership share an anti-Western, fundamentalist Islamic outlook with their Iranian counterparts, although historically, Pakistan's Sunni Muslims have not made common cause with Iran's Shias.

Still less is known about the origins of Iran's heavy water production capabilities. Iran has now declared that it will place the Natanz facility under IAEA inspection to ensure that its output is used only for non-military purposes; under existing IAEA rules Iran need not do the same for the Arak plant. But inspections will not solve the Iranian nuclear challenge.

First, the United States has declared its view that Iran has violated the inspection requirements of the NPT, in particular because of its failure to declare the predecessor facility to the Natanz plant. Given this history, Washington must now be concerned that, like Iraq, Iran will now merely go through the motions of complying with the IAEA system, while continuing to pursue clandestine nuclear activities. Indeed, during the UN debate in the run-up to the war against Iraq, the Bush Administration declared that inspections - even those of the UN Monitoring and Verification Commission, which had far greater powers than the IAEA - could not effectively disarm a state intent on retaining weapons of mass destruction.

No less troubling is the "break-out" scenario. Under the NPT, Iran is permitted to enrich uranium, even to weapons grade, as long as the material is kept under IAEA inspection. The treaty also permits states to withdraw from it on 90 days notice, if its supreme national interests are threatened.

Thus, even if Iran complied impeccably with its IAEA obligations, over time, it could amass a stockpile of enriched uranium. Then, if at some future juncture it found itself threatened by the United States or a resurgent Iraq, it could withdraw from the NPT, seize this stockpile, and manufacture nuclear weapons in a matter of weeks. Indeed, even if it produced stocks only of low-enriched uranium of the type used in the Bushehr reactor, Iran's centrifuge enrichment plant could be rapidly modified to "re-enrich" the material and bring it to weapons grade in a few weeks' time.

What options remain for constraining Iran's nuclear ambitions? If the Bush Administration can rally the international community to condemn Iran and isolate it diplomatically, it may be able to push Iran for concessions. The first would be for Iran to accept the "Additional Protocol" to its safeguards agreement. The protocol, developed after the 1991 Gulf War, would give the IAEA de jure authority to hunt for suspect plants and to keep tabs on activities beyond the agency's usual mandate, like heavy water production. If that were coupled with Iran's agreement to freeze the Natanz and Arak facilities, without operating them, the United States and other concerned parties might breathe somewhat easier.

Unfortunately, with Iran's revolutionary faction still controlling the country's national security policy and seemingly more emboldened each day as it sees new opportunities for influence in Southern Iraq, the prospects for such a turnaround in Iran's nuclear posture appear all too distant.

Leonard S. Spector is Deputy Director of the Monterey Institute Center for Nonproliferation Studies and leads its Washington, D.C., office. From 1997-2001, he served as Deputy Assistant Secretary of Energy for Arms Control and Nonproliferation.