Kazakhstan Caught in Great Power Rivalry

Kazakhstan Caught in Great Power Rivalry

WASHINGTON, DC: President Nursultan Nazarbayev’s resignation from leadership marks an end of an era for Kazakhstan – a country he has ruled since 1989, when it was still part of the Soviet Union. As Central Asia’s largest and richest country that borders revisionist Russia and rising China, Kazakhstan could become the epicenter for great power competition as Beijing seeks global dominance at the expense of the United States and Russia. As Kazakhstan’s regime undergoes transition, so will the country’s foreign policy and a regional dynamic that centers on triangular competition among Russia, China and Central Asia over natural resources and markets. How China positions itself in Kazakhstan and Central Asia could become a litmus test of Beijing’s economic diplomacy and geopolitical aims in challenging Russia.

China’s rising power will drive the greatest shift in geopolitics over the coming decades, raising a challenge to the US-led world order with Beijing’s growing influence in Europe, Asia, Africa and beyond. Central Asia is China’s neighborhood, and the nation shares borders with Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan and Tajikistan. China’s interests have been predominately economic to date, though political and other influence can be expected to increase in the coming years.

The region’s three energy-rich countries of Kazakhstan, Uzbekistan and Turkmenistan have been attractive for an energy-hungry China seeking to ensure the needs of its domestic consumers and industry. Kazakhstan, particularly rich in oil reserves, also has considerable gas reserves, including shale gas and only a few years ago used Russian territory to export many of Central Asian natural resources. However, in 2009 Kazakhstan opened among the first of the region’s large non-Russian-controlled oil export routes– the Atasu-Alashankou oil pipeline to China’s Xinjiang region.

The Central Asia China natural gas pipeline, funded and implemented by China, has since exported predominantly Turkmen as well as Kazakh and Uzbek gas to the Chinese market since 2009. By 2015, the pipeline’s third line, with total capacity of 55 billion cubic meters, was completed. The region’s growing gas trade and Chinese investment translate into strengthening economic and political ties between China and the three countries.

Beijing’s Belt and Road Initiative, pursued since 2013, is a keystone project intended to create an economic and transport corridor to increase regional interconnectivity in Eurasia and expand Chinese economic leverage. The initiative is based on a series of bilateral agreements between China and the Central Asian countries as well as on the work of the Shanghai Cooperation Organization, which also includes the Central Asian countries. These developments continue to strengthen China’s influence in Central Asia at Russia’s expense.

Chinese-Kazakh relations are also not without tensions, especially on issues of ethnic minorities and migration. Kazakhstan's transition of power could spur China to release more detained Kazak-Chinese, allowing them to return to or resettle in Kazakhstan. UN officials have estimated that China has detained more than 1 million Muslims, many of ethnic Kazakh backgrounds, prompting some critics in Kazakhstan to accuse their own government of appeasing China for trade. Nazarbayev’s successor must strive to manage the delicate relationship.

Beijing also has a strategic relationship with Moscow, turning to Russia to meet its natural gas needs via pipeline projects such as the Power of Siberia. This has created a triangle of competition. On the one hand, Russia and China compete for influence and access to natural resources in Central Asia, while on the other hand Central Asia and Russia are potential competitors to supply China’s energy needs.

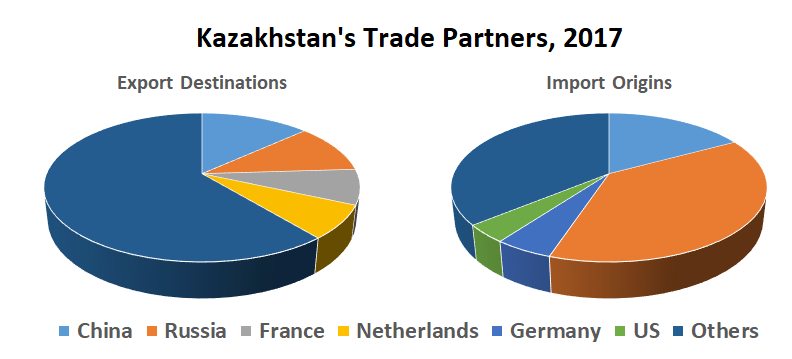

Trade surplus: Kazakhstan exports totaled $44 billion including crude petroleum, refined copper and petroleum gas; imports totaled $30 billion and include refined petroleum, medicaments, equipment and cars (Source: Observatory of Economic Complexity)

Cooperation among the Central Asian states has been weak as they focus on their bilateral ties with China or Russia. If there was more regional cooperation, then balancing against China or Russia as well as strengthening relations with the US or the EU would be feasible. However, the new generation of Central Asian leaders – lacking the common Soviet-era ties and early formation of their predecessors – are even less likely to succeed at regional cooperation.

To achieve its ambitions of great-power status, China will inevitably step on Russia’s toes in Central Asia. Here, Moscow’s long-held hegemony remains tenuous in the face of regional and geopolitical changes. Most Central Asian countries joined various Moscow-led economic and political blocks such as the Commonwealth of Independent States and the Eurasian Economic Union, but have remained cautious of deeper political integration. Following Crimea’s annexation, Kazakhstan has the most reason to be concerned due to a sizable Russian population, about 20 percent, with most residing in energy-rich territories along the Russian border. This could make an appealing target to Moscow as described in my book Beyond Crimea: The New Russian Empire.

Russia’s geopolitical interests in Central Asia focus on maintaining its special zone of influence despite China’s growing role. President Vladimir Putin named Kazakhstan Russia’s “closest strategic ally and partner.” The two states share a border of more than 6,400 kilometers, and Kazakhstan serves as a buffer for Russia from the rest of Central Asia, Afghanistan, Iran, Pakistan as well as from transnational extremist threats and the drug trade.

Kazakhstan hosts a number of Russian military testing and strategic sites such as the Baikonur Cosmodrome space-launch facility, space surveillance and early-warning radar stations, and antiballistic missile-testing ranges. As the world’s leading uranium producer contributing to nearly 40 percent of the global total, Kazakhstan is a key supplier for Russia’s nuclear industry.

Unlike Russia or China, the United States is not a regional player in Central Asia, but a global power and leader of the North Atlantic Treaty Organization. Washington has an interest in maintaining regional stability and peace. In the post-9/11 world, US interests in Central Asia deepened as it launched a war on terror. In the early 2000s, during the war in Afghanistan, the United States established military bases in Kyrgyzstan and Uzbekistan while all five countries joined NATO’s Partnership for Peace program. Subsequently Uzbekistan agreed to serve as a transportation hub for US and NATO operations in Iraq. The region’s vast oil and gas reserves also attracted Western multinational corporations, accelerating the region’s energy exploration.

With US efforts to withdraw from Afghanistan and inward-looking foreign policy during the Obama and Trump administrations, Washington has paid less attention to Central Asia. This was evident from little American interest expressed during the transition of power following the 2016 death of Uzbekistan’s President Islam Karimov or Turkmenistan’s transition in 2007 when Gurbanguly Berdymukhamedov, the second president, came to power.

The Trump administration has an opportunity to revive US engagement in the region. Geographic realities limit the West’s interests, but the US and the EU could play a constructive role in Kazakhstan’s power transition, supporting the country if it chooses to pursue a democratic path and encouraging diversified economic development. Through stronger diplomatic relations with the West, Kazakhstan could better balance against the influence of Russia and China.

Bordered by a revisionist Russia and rising China, during a time of Western disengagement, Kazakhstan will likely face serious geopolitical challenges under Nazarbayev’s successors. A changing global order will play out in this region, and Central Asian states have a role in whether Russian-Chinese collaboration can endure in the absence of a veteran autocrat skilled in playing the great powers against one another for balance. The next leader will calculate the potential for democratization, and relevance and utility of relations with the United States and Europe, before considering whether to promote democracy and human rights in this region. In this era of geopolitical competition and regime transition, neither Russia nor the Central Asian states have the will to resist China. The best foreign policy option for Kazakhstan and other countries of Central Asia would be to boost regional cooperation and resist becoming over-dependent on China or Russia, by strengthening ties with the US and the EU.

Agnia Grigas, Ph.D., is a geopolitical economist and political risk advisor. She is a nonresident senior fellow at the Atlantic Council and author of “The New Geopolitics of Natural Gas” and “Beyond Crimea: The New Russian Empire.” Follow her on Twitter: @AgniaGrigas and www.Grigas.net.