Latin America’s Explosive Debt

Latin America's Explosive Debt

Investors lured to Latin America during the nineties by the siren song of economic reform, deregulation, better government, and privatization, are wondering why the region is again on the brink of a financial calamity. Frequent trips to the financial emergency rooms of the world do not seem to have brought about permanent change. No wonder frequent visitors, like Argentina and Brazil, doubt whether the prescribed medicine - liberalism coupled with macroeconomic stabilization by dint of fiscal austerity - is really suited to the ailment.

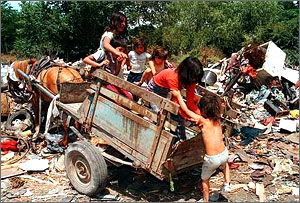

In most Latin American countries, the gap between richest and poorest is among the world's widest. Liberal economic policies - grafted onto a society with no shared sense of social engagement - draw shaky support. Essential decisions concerning trade, education, taxes, and social insurance garner weak political consensus because the consequences are dramatically different for citizens at different economic strata. Distribution inequities generate dramatic swings in the economic platforms of political parties and make fiscal consensus elusive.

Rather than closing the income gap, liberalism revealed the inadequacy of government institutions. Economies pumped up by international investment did not provide basic services such as health, education, adequate communications, or transportation infrastructure. Moreover, accountability arenas are weak, allowing the caretakers to steal what they were mandated to protect. Consider the legacy of Argentina's champion of market-friendly reforms, Carlos Menem. His two terms in office were marred by a Swiss-bank-account scandal and allegations that he personally profited from illegal arms shipments and bribes.

Economists tried to convince governments of the merits of their narrow macro-economic point of view, overlooking the political and social risks that were out of their point of reference. A lack of attention to social tensions undermined the soundness and quality of what would have been very good advice. Today, money is leaving the region, driven out by doubts about the durability and momentum of ongoing reforms.

THE IMPENDING CRISIS

The danger of policy reversal looms extremely large in Brazil where financial markets panicked when Leftist candidate, Luiz Inacio Lula da Silva, prevailed in the polls against Jose Serra, the center-right candidate, in the Presidential campaign of 2002. Lula's ascendancy creates uncertainty about post-electoral monetary policy because he advocates policies that would drag Brazil to the left, in defiance of recent market reforms.

As fear of policy reversal chills the investment climate in Brazil and drives money abroad, the currency also weakens. Investors, anticipating a debased currency, sell reals, in effect causing what they feared. A debased currency, in turn, is likely to initiate a cycle of wage demands and inflation.

Although the capital infusion by the IMF allows the government to buy time with creditors, it also allows the politically connected to escape at a better rate than the average citizen. The appearance of political favoritism at the Central Bank's exchange desk will help ignite claims that the IMF intervention subsidized capital flight - the exact opposite of what it is intended to accomplish. Moreover, because the money can leave as fast as it entered, the Brazilian people receive little comfort but bear the burden of repaying the loans. With each bailout, the burden increases, making it harder to achieve a long-term, stable position from which to resume growth.

Political leaders have been unable to steer the Brazilian economy out of these dire straits. Since the election of market reformer Fernando Henrique Cardoso as President in 1994, public debt has soared from 29 to 60 percent of GDP while income per person has grown annually by a slow 1.3 percent. Cardoso scored stellar grades from the international banking community, but the cross border loans that his government attracted (totaling $140 billion) have not prevented the stagnation of living standards. In fact, income per person has improved by less than 9 percent since 1980.

BRAZIL'S PROBLEMS ARE LATIN AMERICA'S

Brazil's financial instability is emblematic of the region's woes. Weak capital markets constrain large numbers of the population from contributing to economic growth throughout Latin America. A Milken Institute study of capital access in 98 countries ranked Costa Rica, Columbia Venezuela, Ecuador, and Paraguay at the bottom at 82, 84, 87, 88 and 89 respectively. Many other Latin American countries fared only a little better. "Equity markets are particularly narrow in Latin America; the ratio of the number of firms to population is roughly one third of the world mean, whereas the ratio of the number of IPOs to population is more than 10 times smaller than the world mean".

As banks make loan decisions in such a weak capital market, they tend to favor older and larger firms that are regarded as more likely to repay debts. The established firms gain security but the economy loses an important source of job growth. Only in Chile, the region's best performer, does credit from the banking sector to the private sector exceed 50% of GDP. In Peru and Argentina, the ratio is around 20 percent. The fact that companies work with a very small debt load contrasts sharply with companies in Asia. Latin American firms are not giving themselves the venture capital they need to replicate the success of Asian firms. UBS Warburg estimates the ratio of debt to equity is only 26% in 2001. This can be compared with Japan's corporations which maintain debt to equity ratios of about 277%. In South Korea, ratios were about 300 hundred percent when they peaked in 1998, down to 198.3 percent in 2001.

Volatility = Vulnerability

Over the past thirty years Latin America's macroeconomic volatility has surpassed that of any of the emerging markets. By late 1990, the region's average annual rate of inflation approached 1,500%, and income declined by 10% relative to the early 1980s. Macro-instability erodes savings and undermines broad pledges to honor contracts. Unfortunately, potential investors both domestic and international perceive fiscal discipline to be reversible, because for every Cardoso there is a populist Lula just around the corner. Fears of reversibility undermine the credibility of government finance, increase the cost of capital finance, and cause governments to incur higher interest rates."

Poorly functioning legal systems and the lack of good credit information undermine small enterprise development. Laws do not enable businesses to become legal entities in their own right. Many entrepreneurs start out in the informal sector because start up procedures for independent businesses are cumbersome. Once embarked on informal sector activity, the transition to formal status is elusive.

The convergence to government debt

Although Latin America's citizens are putting aside large sums to invest, the private sector is starving for funds. Savings are going to government debt. In three of the region's four major capital markets, Argentina, Brazil and Mexico, government debt is a huge part of total debt capitalization. Chile is the exception.

The fundamental weakness of Latin American financial markets is the extent of government borrowing. Other avenues of investment have been sealed off by an absence of supporting institutions. For example, corporate governance is exceptionally poor, especially in the protection of the rights of minority shareholders. Despite a growing awareness of the need to make legal changes and widespread public recognition of the shortcomings, weak enforcement persists. Financial sector officials are not empowered to monitor company accounts objectively and there is no incentive for companies to disclose since they are then vulnerable to expropriation. In Brazil, regulators can even be sued privately for their actions as civil servants. What better way is there to paralyze their activities? As a result, equity markets are weak and their failure to develop means an over dependence on banks whose collapse can devastate the entire financial sector. When asked why investment banks or brokerages do not set themselves up as market makers, the usual answer is volatility. The market is never stable enough for a market maker to emerge from the private sector. But there is another reason - the concentrated monopoly power of a few large firms in most industries. With the exception of Chile, which has strong shareholder rights, Latin American countries have higher ownership concentrations than the world mean.

Moving away from the financial sector, a long list of institutional failures has not been corrected during a decade of macroeconomic adjustment. These include a general absence of predictability in budgeting and rule making and significant delays of audits in government and private sector accounts. Although a lax regulatory environment increases the risk of socially costly bank failures, regulatory weakness benefits some interest groups and their political sponsors.

The weak fiscal positions of government often stem from the use of public money to dispense a wide range of private benefits through vast patronage networks, ranging from lucrative business contracts to keep the rich happy, to plentiful jobs for the poor. Even a sophisticated reformer such as Argentina's former president, Carlos Menem, succumbed to patronage based governance. One term of austerity to get Argentina back on its feet was followed by a second term of borrowing. He spent the money on deals to drum up political backing, while rolling back the good policies that earned him the credit to borrow in the first place. A full second term of misgoverning left little in the kitty for his successors, who had to decrease salaries and dramatically increase taxes to cope with the large deficits they inherited. One World Bank study ranks Argentina as the world's most corrupt country (when ranked according GDP per capita); however, even at the peak of his reformist zeal, Menen never undertook reforms of Argentina's public sector. Argentina needed macroeconomic stabilization, but also greater faith in the condition of law enforcement, reform of the organization of government, and the development of self-enforcing social norms that foster entrepreneurship, trust and respect for legality. The quality of public services is grossly inadequate, and political appointees who dominate the top levels of the civil service decide who gets electricity and phone service. Nevertheless, so called `second generation reforms' of the organization of government were neglected. Instead, Menen concentrated on privatizations that did little to improve competition or efficiency. The political struggle within the cabinet took priority and it required players to have access to patronage.

OPACITY IS GOOD FOR THE FOX

Argentina's spectacular collapse in 2001 made it a poster boy or some would say wiping boy for faults that are endemic to the region. Nevertheless, large public sector budget deficits throughout the region reflect a familiar pattern of the public sector being a source of private patronage. Institutions that create a fiscal illusion allow this pattern to persist. Non- transparent fiscal transfers hide long- term social costs. Powerful segments of society like opacity, giving Latin American governments few incentives to create effective foundations for long term contracting and the management of financial risk. Growing middle class aspirations have, fortunately, created a domestic constituency, who wants to make society more competitive and less top-heavy.

Meaningful institutional reform is hostage to the same distributional conflicts that arouse partisan conflicts over fiscal decisions. As a result of these perverse domestic political incentives, globalization has not helped the region to find a solution for its divisive politics. Instead, global financial market access has reduced the cost of political distortions. The large deficits that appeared in the 1970s coincided with international financial market access and liberalization. In the optimistic world of unlimited horizons in the 1990s, the region's strongest economies seemed to enjoy great prospects, which allowed them to raise money easily from international capital markets. Unfortunately, easy access to international capital markets may have reduced the effects of large deficits on interest rates, and, more generally, made it easier for fiscally irresponsible governments to borrow.

SOCIAL POLARIZATION

A combination of proportional representation with deep economic divisions is the main source of Latin America's severe policy failures. Very polarized societies produce single parties that tend toward strong partisan ideologies. Partisan conflicts over how to resolve issues of fiscal policy cause boom burst cycles and heighten uncertainty about policy.

The region tolerates enormous tax inequities, some are endemic to emerging nations. Specifically, direct taxes are difficult to levy both because the wealthy oppose such levies and because the inherent administrative costs of direct taxation are very high. Like most poor countries, Latin American governments rely on indirect taxes, which are typically regressive and difficult to increase.

However, the absence of a social consensus for tax reform is the key reason for big borrowing. Systemic tax reform is needed, not piecemeal tinkering with the economy. Tax reform is the most difficult issue for governments in the region to tackle; it is easier to borrow more than to settle vast ideological differences over fiscal management. Until those divisions are eliminated, financial markets will demand a risk premium that compromises the welfare of all who live in the society. Finally, inadequate finance means that many citizens are barred from making a contribution to or enjoying the benefits of economic growth.

CONCLUSION

Why do leftist candidates that have earned a nationwide following - such as Evo Morales of Bolivia, Hugo Chavez of Venezuela, Elisa Carrio of Argentina, and Lula de Silva of Brazil - strike fear into the heart of investors? Their appeal to voters increases because governments associated with open-market policies suffer from a crisis of legitimacy. A legacy of insider privatization that further concentrated wealth without improving performance has hurt the cause of liberalization.

If Latin America is to escape populism in economic policy, its causes must be addressed. Radical inequality fosters insurrection, not cooperation, and makes heroes out of those who, like Bolivia's Morales, throw stones at the symbols of corporate power. Latin America will continue to disappoint until it can exit this world of politically driven business cycles. A brave new political realignment, not more international loans, are needed to get capital and labor to collaborate and design a social contract that restores legitimacy to the political processes, creating states that provide Latin America's inhabitants access to capital and opportunity.

1 Shahid Javed Burki and Guillermo E. Perry, 1998, Beyond the Washington Consensus: Institutions Matter, The World Bank, Washington D.C.

Hilton Root is senior fellow at the Economic Strategy Institute in Washington DC.