Lessons from History: Globalization Then and Now

Lessons from History: Globalization Then and Now

PRINCETON: Many people wish that globalization would simply stop. After September 11, some critics of globalization, such as the British philosopher, John Gray, thought that the process they detested so much had indeed come to an apocalyptic end. This view fails to specify what has replaced globalization; it is also wrong. The world is still very interdependent, though that interdependence makes for a great vulnerability.

Since September 11, the debate about globalization has changed in two significant ways. The first is a direct product of the terrorist attack. Every part of the package that had previously produced such unprecedented economic growth in many countries - the increased flow of people, goods, and capital - now seemed to contain obvious threats to security. Students and visitors from poor and especially from Islamic countries might be "sleeper" terrorists; or they might become radicalized through their experience of western liberalism, permissiveness, or the arbitrariness of the market economy. It soon became apparent that customs agencies scarcely controlled the shipment of goods any longer, and that explosives, or even ABC (atomic, biological, chemical) weapons might easily be smuggled. The free flow of capital, and complex bank transactions, might be used to launder money and to supply funding for terrorist operations.

It is natural and legitimate to suggest that all these areas should be subject to more intense controls. But every sort of control also offers a possibility for abuse by people who want controls for other reasons: because skilled immigrant workers provide "unfair" competition, because too many goods are imported from cheap labor countries; or because capital movements are believed to be destabilizing, producing severe and contagious financial crises. A new debate about the security challenge offered the chance to present older demands for the protection of particular interests in a much more dramatic and compelling way. Protectionists of all sorts suddenly had a good story.

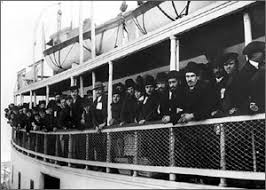

The demand for more controls - almost always dressed up as a concern for national security - was characteristic of past eras in which globalization broke down. The most chilling experience of the intensification of controls during the last century was in the Great Depression. Many of the policies implemented in the 1920s and 1930s (immigration restriction; or trade control) were not fundamentally novel, but they could be dressed up in a new way as answers to the security issues raised by the First World War. They were more extreme versions of ideas developed in the nineteenth century as protective shields from the fierce winds of international competition. As the world economy looked more disorderly and threatening in the aftermath of the First World War, such solutions appeared even more attractive. What had before 1914 been safety nets against excessive globalization became after the World War gigantic snares which now strangled the world economy. Capital controls were introduced to combat speculative exchange movements, quotas to supplement tariffs in restricting unwelcome trade.

People who might move capital (because they thought that regimes were unstable) were now depicted as national traitors. In Central Europe, against a background of ferocious anti-Semitism, capital control legislation was used in particular to penalize Jews. In a recent analogy, during the Asian crisis of 1997-8, in many ethnically diverse states, such as Indonesia or Malaysia, it was claimed that the Chinese population saw itself as belonging to a greater China, and was particularly liable to move funds, and hence was a security risk. Today, with increased uncertainty and a high likelihood of war in the Middle East or the Gulf, it is easy to think that Arab or Islamic transactions will be looked at as subversive of security.

Terror has helped to create a new mood of suspicion, of polarization, and of a search for enemies - and that indeed was one of its purposes. In this way it has inevitably enhanced the vulnerability of the world to new economic shocks.

The second new development looks as if it is independent of the terror issue, although it too revolves around the discussion of America's role in the world. Paul Krugman quickly concluded that the impact of Enron would be more dramatic than the damage done by September 11. The combination of worldwide stock price declines with the revelation of some major cases of accounting fraud in the United States has produced a moral crisis of capitalism. Particularly outside the United States, countries, politicians and business leaders who previously listened to Americans proclaiming the superiority of the American way of life, now have a quite acute Schadenfreude. Enron was the banana skin on which American capitalism slipped. Prominent European business executives, like Jean-Marie Messier, Ron Sommer, and Thomas Middelhoff, are blamed and sacked for being too Americanized. In many countries, a fierce debate started about the pay and compensation of senior business figures.

Again, there are historical parallels for such a response. In previous periods, as today, greater market integration, and increased long distance trade, created new opportunities and new riches. But in the past, many people felt that there was something illegitimate about the great gains and the resulting large inequalities. The Renaissance and the great age of European explorations was also a period of great poverty (because of the population growth rather than because of the dynamism of the economy). Moralists such as the fiery Florentine friar Savonarola or the dyspeptic German Martin Luther fulminated against luxury and long distance trade. Luther believed that "foreign trade, which brings from Calcutta and India and such places wares like costly silks, articles of gold, and spices - which minister only to ostentation but serve no useful purpose, and which drain away the money of land and people - would not be permitted if we had proper government and princes." In the late nineteenth century, Karl Marx and Richard Wagner and many others excoriated the ills of luxurious and sinful capitalism. The expansion of trade had often been associated with new opportunities for greed, corruption, and self-enrichment; and many commentators rapidly reached the conclusion that this was all there was to the new developments.

Most of the protesters then thought in terms of some simple moral alternative, theological or quasi-theological. In the mid-twentieth century, there were apparently simple and appealing alternative models - offered by leaders who saw it as their mission to formulate a new philosophy for the state, Mussolini, Hitler, or Stalin.

Today's globalization, apparently driven by financial flows and financial institutions, offers many examples analogous to the scandals of the past. Enron looks as if it will be the starting point of a new debate; but it is quite unclear what will be the outcome of that debate. An immediate response is to call for more regulation, but regulation is always designed to do something. What should the goals of a new regulation be?

In the twentieth century, the regulatory traditions reflected one of two opposed social philosophies: one conservative, designed to stop new developments that might be disequilibrating or disturbing; and the other social democratic, designed to provide compensation for the victims of change and innovation. But today these old political movements of the twentieth century are largely exhausted. Classic conservatism is dead because the world is changing too rapidly for conservatism as stasis to be coherent or appealing any more. Classic socialism has also largely disappeared politically, because the rapidity of change and the mobility of factors of production across national frontiers erodes traditional labor positions in exactly the same way. The bankruptcy of these two very respectable but now quite out-moded positions leaves the path open for a new populism, based on an anti-globalization groundswell, that is inward-looking and likes the idea of the revival of the nation as a protective bulwark against foreign goods and foreign migrants and foreign ownership. The populist reformulations are fundamentally at odds with the universal values which still form a core of western political traditions.

The alternatives that at the moment command more electoral sympathy are anti-corruption (in practice anti-incumbent) movements, and consumer-interest advocacy. Politics in advanced industrial countries have become in the post-Cold War, new globalization era, increasingly centered around this twin set of issues, which do not raise either classical redistributional themes, nor fundamentally challenge the process and progress of globalization. All of these developments had become quite apparent before the stock market collapses and the corporate scandals.

Sometimes it is claimed that this transition is due simply to the end of the Cold War, which in providing convenient external enemies held politics frozen in place. This thesis is true to the extent that no other compelling and over-arching issue replaced the Cold War. Then more or less simultaneously, the Italian Christian Democrats disintegrated, the British Conservative Party suffered from a succession of "sleaze" cases, France's political parties competed in trading revelations and allegations about François Mitterrand's corruption on the one hand and the affairs of Jacques Chirac's Gaullists on the other, the funding practices of Helmut Kohl's "system" were exposed, and President Bill Clinton moved from one fund-raising and campaign finance scandal to another. Enron and Halliburton appear to offer another type of link between business and political corruption.

Exposure of corruption as the major form of domestic politics in every industrial country has brought a politics of negativity. A more positive modern political direction is concerned with the protection of consumer interests: the restriction of tobacco advertising, automobile safety, and - for Europe - most importantly, food safety in the face of a succession of scares about disease and infection.

Almost always these new political issues are attached to the globalization debate. It is the products from far away that pose a threat. For a long time, before the eruption of the BSE and then the foot and mouth disease problems, the European food safety obsession focused on the alleged (and undemonstrated) perils of U.S. hormonally fed beef, and then on the possible dangers of genetic engineering. Then BSE and foot and mouth seemed new cases of the perils of trade in foodstuffs that went across national borders. Continental Europe saw them as cases of British lack of hygiene and recklessness, while Britain blamed foot and mouth on waste products imported from China.

Disgust at traditional politics, revulsion against the immorality of the market, and the search for home grown answers to the moral crisis: these were and are the characteristics of the downward phase of the cycles of integration and disintegration which the world has repeatedly seen. But at the moment there is no simple and coherent ideological solution to the challenge posed by globalization, unless it is the very radical one of some versions of Islamic fundamentalism.

Harold James is a professor of history at Princeton University.

Comments

This would be a big help for my studies