Lessons from an Unpunished Crime in Pakistan

Lessons from an Unpunished Crime in Pakistan

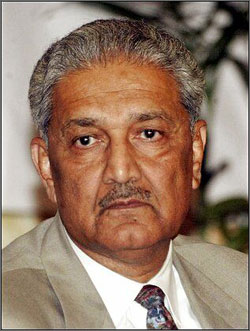

WASHINGTON: A.Q. Khan got off lightly, sending disturbing messages about US and Pakistani attitudes toward proliferation. After setting himself up as the Wal-Mart for nuclear weapon shoppers in Libya, Iran, North Korea, and others who have yet to be identified, Khan, the self-proclaimed father of the Pakistani nuclear bomb, has admitted guilt as charged by Pakistani General-turned-President Pervez Musharraf. In quick succession, a penitent Khan met with the khaki-clad President and went on Pakistani television to take all the blame and to absolve the Army. Musharraf then suggested leniency to his Cabinet, which readily agreed. The President wasted no time issuing a pardon in light of Khan's heroic service to the nation and, for good measure, allowed Khan to keep the fortune in money and real estate he amassed from his illicit nuclear commerce.

Meanwhile, Musharraf continues to hound former Prime Minister Benazir Bhutto to pay back to the nation her fortune of ill-gotten gains derived from corrupt government contracting.

There are two morals for the proliferators of nuclear and missile technology - if that is the right word for this strange story. The first is don't get caught. Khan's real estate holdings were no secret in Pakistan, nor was his penchant for foreign travel. Foreign intelligence services long-suspected Khan's dealings, as well as the difficulties his lab at Kahuta was having in producing nuclear warheads and missiles.

Pakistani officials responded to questions about nuclear transactions with blanket denials. This defense began to unravel when US intelligence agencies pieced together the existence of a uranium enrichment program in North Korea. Suddenly, the question of what Pyongyang got in return for bailing out the Khan Research Labs by transferring No Dong missiles could be answered with certainty: The Pakistani cargo plane that picked up the missiles, which were then re-labeled as the indigenously-built ‘Ghauri', was engaged in barter transactions that involved the provision of centrifuge technology.

Soon thereafter, Iran's uranium enrichment program, which was publicly revealed by an opposition group to the ruling ayatollahs, became the center of international attention. It was implausible enough for Tehran to claim it needed nuclear power for electricity, but there's no way that enriched uranium can be used to light street lamps. With clear evidence of an intent to acquire the entire fuel cycle necessary for bomb making, Iran's ayatollahs decided to take the heat off, to freeze the program temporarily, and to allow inspectors from the International Atomic Energy Agency to gain extensive access to plants under construction. Iranian officials also confirmed what the inspectors could plainly infer - that the centrifuges came from Pakistani sources.

Next it was Libya's turn. After a shipment of centrifuge parts was intercepted in the fall of 2003 headed for Libya, Muammar Qaddafi decided to come clean. In return for a lifting of sanctions and the prospect of foreign direct investment, he invited US and British officials to close down and cart out his bomb-making project. More equipment from A.Q. Khan's netherworld of nuclear commerce was uncovered. The most extraordinary find, as reported by the New York Times, were actual blueprints of a nuclear warhead of Chinese parentage that was given to Pakistan by Beijing to help the Khan Research Labs out of an earlier jam.

At this point, Pakistan's flat denials of illicit nuclear commerce were shredded beyond repair. Under heavy pressure by the United States to roll up Khan's network and to acknowledge misdeeds, Musharraf set in motion the investigation and public humiliation of Pakistan's national hero. Which leads to moral number two for future proliferators: Be an indispensable ally to the United States in the global war on terror.

If A.Q. Khan resided in another country, or if Pakistan were led by the religious leaders who are eager to unseat Musharraf, the Bush administration's response would have been far different. But Washington knew that a public trial of Khan would have put a club in the hands of Musharraf's many enemies while risking the disclosure of official government and high-level Army support for some of his transactions

Khan confessed to missteps driven by Islamic solidarity - an explanation that conveniently overlooks the money he pocketed and his dealings with North Korea. Two other rationales for Pakistan's nuclear commerce - paying back governments that helped to finance the program and seeking foreign assistance to overcome problems with domestic production lines - were also behind Khan's travels. These transactions surely required the authorization and full consent of army chiefs, prime ministers, and a president or two. The quick choreography of Khan's confession and pardon, as well as Washington's muted response, point to a mutual desire not to delve publicly into history.

In return for this pact not to question Khan's fiction that he, alone, was to blame, the Bush administration appears satisfied to roll up his supply network while Pakistani officials conduct a more thorough housecleaning at his lab. Musharraf will again promise that these transactions will not happen again. He gave Secretary of State Colin Powell a pledge of 400 percent on this score after US intelligence tracked the delivery of centrifuge parts to North Korea in the fall of 2002. Khan's shipment to Libya was intercepted one year later. If future transactions occur for reasons of state - that is, to repay foreign governments that have called in their notes or to overcome production bottlenecks - the Bush administration will have a tough decision to make. Musharraf and his advisers will cross this bridge if they have to, but they have good reason to presume that Bush would be forgiving, as long as Pakistan makes progress in cleaning up messes, and as long as its support remains essential in nabbing Osama bin Laden and the remnants of his al Qaeda network.

What is the net effect of the A.Q. Khan affair on global efforts to stop and reverse proliferation? The good news is that A.Q. Khan is no longer a player, that venality and Islamic solidarity are no longer acceptable drivers for proliferation in Musharraf's Pakistan, and that a very successful network of covert transactions is being put out of business. The number of states seeking nuclear weapons and missiles to carry them has been reduced significantly. Saddam is gone, and Libya has decided to go straight. This leaves Iran, which has agreed to a temporary freeze on fissile material production, and North Korea, which might be amenable to a deal - if and when the Bush administration is prepared to offer one.

The bad news is Khan has proved that extraordinarily damaging blueprints and parts can be surreptitiously exchanged for cash, and that this information can fit into CD-ROMs as well as military cargo planes. Covert supply networks can be reconstituted, but the market is likely to shift from sophisticated nuclear weapons to crude forms of nuclear terrorism. Global controls and safeguards on dangerous nuclear material are more essential than ever - and this work has barely begun.

Michael Krepon is founding president (1989-2000) of the Henry L. Stimson Center and author of “Cooperative Threat Reduction, Missile Defense and the Nuclear Future” (Palgrave, 2003).