Leveraging Ambiguity in Foreign Relations

Leveraging Ambiguity in Foreign Relations

MOSCOW: Ambiguous behavior, doctrines and statements have gained popularity as foreign policy instruments among great and smaller powers alike over the last decade. Ambiguity – intentional lack of clarity about one’s goals and plans – has contributed to the rise of unpredictability and associated risks in global affairs. And yet, ambiguity can be “constructive,” bringing clear benefits in the field of negotiation and conflict resolution. Foreign relations of Russia, a major power aspiring to increase its regional and global imprint, and some of its international counterparts since the end of the Cold War offer insights into the costs and benefits of ambiguity.

Ambiguous action entails significant risks, but is attractive, too, by quickly helping actors to expand freedom of maneuver in the world stage – witness Iran or North Korea being offered concessions by the international community in exchange for reduced ambiguity about the goals and scope of their nuclear programs. Ambiguity can be a force for common good if practiced consensually, that is, if all sides in a negotiation agree to a moderately ambiguous deal in order to end the talks on a positive note and avoid escalation of their conflict. A takeaway for practitioners could be to practice ambiguity together with counterparts and avoid doing so alone. Examples include the agreement on German reunification, the New START Treaty and the Minsk agreement on eastern Ukraine.

Russia has struggled for say on a variety of issues considered of key importance for its security – preventing NATO enlargement, US missile defense deployments or “color” revolutions. But nobody listened, at least according to the official Russian narrative. So the Kremlin decided that forcing its counterparts to recognize Russia’s higher status by means of ambiguous actions, doctrines and statements may work better than conducting decade-long protracted negotiations on each area of concern.

Over the last few years, Russia has been increasingly resorting to ambiguity in its quest for a higher status vis-à-vis its Western counterparts and primarily the United States. Moscow has been seeking to elevate its status in the form of recognition by its peers and the right to act freely under certain circumstances. For example, peers may recognize that status allows a nation to veto enlargement of a rival alliance.

Interestingly, authority and, by implication, status are fungible and non-expendable. Status gives a nation a say on a variety of issues, not just alliance enlargements, while lessening resistance or even discontent from its counterparts. And a nation can reinforce or even raise status and authority by employing that authority. Status is “anti-fragile” – with more use, the stronger it becomes. As a result, over the recent years, Moscow has tried to leverage ambiguity in pursuit of a higher status. Examples include the graphic demonstration of new weapons by President Vladimir Putin in his March 1 address to the Russian parliament, plausible deniability of Russia’s involvement in the Ukraine conflict and the “escalate to de-escalate” doctrine – supposedly envisaging a low threshold for the use of a nuclear weapon – attributed to Russian military officials despite their ardent denials.

All of those actions, doctrines and statements include elements of ambiguity employed in pursuit of status – recognition of Russia’s right to do what it wants when its interests are affected. However, such “unilateral ambiguity” tactic does entail a number of problems. Claiming status through ambiguity requires a constant upping of the ante in interactions with stronger opponents – status recognition typically sought from stronger, not weaker parties. Also, opponents of the status-thirsty actor may push back stronger than expected, for example, by attempts to isolate or sanction that actor. Another option is disengagement – witness, for example, the Trump administration’s stated disinterest in further arms control agreements with Russia and refusal to be impressed with Russia’s newly announced weapons.

Ambiguous doctrinal statements are often perceived as self-incrimination, difficult to back out from, even if the nation wants to do so. The notorious “escalate to de-escalate” doctrine has proved particularly difficult for the Russian government to shrug off despite the conspicuous lack of official endorsement.

Overall, it is easier to achieve a higher status and receive broader authority by convincing one’s peers that the aspired status is deserved rather than by taking ambiguous and potentially adversarial postures. This conclusion applies not only to Russian foreign policy, but to similar situations in which aspiring great powers seek higher status.

Unlike attempts to attract attention and win concessions with ambiguous behavior, consensual and collective practice of ambiguity can sometimes help resolve antagonistic disputes. Such disputes usually do not allow for definitive and lasting solutions because that would pre-determine loss for some parties and gain for others. In order to conclude negotiations in antagonistic contexts, the sides may find it useful to resort to “constructive ambiguity” – agreeing that some future course of events that the participating parties cannot or may not want to predict at the moment of negotiation closure will shape the ultimate outcome. In a way, that means leaving the final outcome to chance. That seems risky, but if the sides can live with ambiguity in their agreement, then the flexibility of their positions and the chances of resolving the dispute increase. In a way, they are leveraging uncertainty about the future that, in turn, is a result of the stochastic, largely random nature of the social and physical world.

Constructive ambiguity has more than once allowed finding off-ramps from controversy in US-Russia relations. If one looks at a number of prominent cases, one can find a significant element of ambiguity in each:

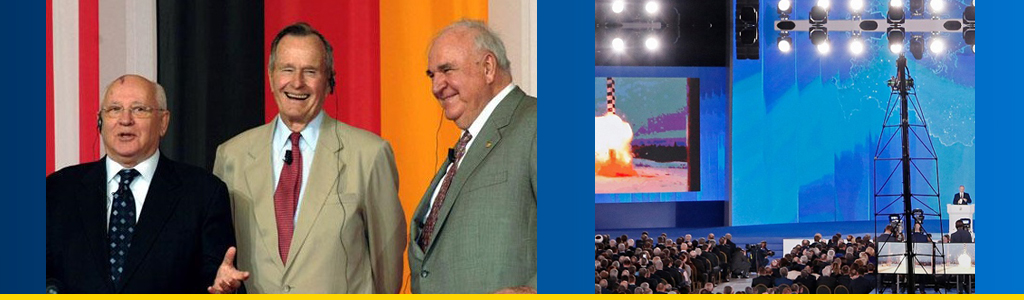

• When Germany, the USSR, and the Western powers negotiated German unification in 1990, all parties appeared amenable to ambiguity in the discussion of future alliance politics. Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev assumed that he had guarantees against NATO rushing to exploit Soviet vulnerability after the reunification. German Chancellor Helmut Kohl was simply happy with any future configuration of military alliances if Germany was allowed to unify, while US President George H.W. Bush and Secretary of State James Baker assumed they were issuing no promises to the Soviet Union regarding NATO’s future.

• Twenty years later, ratification of the New START Treaty only became possible because both Moscow and Washington assumed their distinct interpretation of the role of missile defenses prevailed in the treaty: Russia insisted reductions in strategic nuclear arms were conditional on limits for US missile defense capabilities, while the US Senate made a statement to the contrary when ratifying the treaty.

• Finally, the Minsk agreement on eastern Ukraine, signed in February 2015, notoriously did not contain a clear roadmap leading to a definitive resolution. The parties essentially decided to leave the final outcome to chance, depending on highly unpredictable international and domestic political trends. They needed an agreement in Minsk, and they signed it, at least ensuring a break in armed hostilities and, of course, administering only a palliative medicine.

Agreements based on constructive ambiguity can be successful when each side has reason to believe that circumstances will eventually play out in its favor. The ultimate outcome is likely to differ, falling short of original expectations because of the fundamental complexity of international politics and the world in general. In the end, neither party may find its negotiating position vindicated. But the historical record – including the cases above – shows that the sides are usually less disappointed with the ultimate outcome and less likely to break from the agreement, resume hostilities or demand unrealistic compensation because of the price of reopening the controversy.

Mikhail Troitskiy is a political analyst in Moscow. This article is based on a longer paper, “Leveraging Ambiguity in Russian Foreign Policy: Implications for Theories of Status and Negotiation,” which he presented at a conference on Regime Evolution, Institutional Change, and Social Transformation in Russia: Lessons for Political Science, April 28, 2018, at the MacMillan Center, Yale University.