Libya Exposes Fault Lines in the Mediterranean – Part III

Libya Exposes Fault Lines in the Mediterranean – Part III

NEW YORK: Many factors are behind the revolutions sweeping across the Arab region, including decades of brutal repression, widespread corruption, stagnant development, absence of genuine democracy and meddling of outside powers.

But all these are exacerbated by the region’s demography. Recent high fertility levels coupled with low mortality have produced not only rapid population growth, but also large numbers and proportions of youths aged 15 to 24 years, commonly referred to as “youth bulges.”

Frustration builds as growing numbers of young, educated, urban Arab men and women are forced to confront common trends, including increased competition and diminished opportunities, high levels of unemployment with few productive jobs, delayed marriages, gender inequality and human rights abuses. Also, many of the young adults in Arab cities receive rudimentary liberal arts education unsuitable for the modern economy. More ill prepared are rural youth who migrate to urban centers with little education and few skills.

By virtually any standard, demographic growth of the Arab countries has been extraordinarily rapid. Since 1970, for example, the population of the Arab region – consisting of some 22 countries – has nearly tripled, growing from 128 million to 359 million.

Moreover, while populations of Algeria, Egypt and Tunisia have more than doubled over the last four decades, Libya’s and Syria’s populations tripled, Yemen’s quadrupled and Saudi Arabia’s nearly quintupled. In contrast, during the same period, the population of neighboring Europe grew by 12 percent and the population of most rapidly growing developed country, the United States, saw a 52 percent jump (Figure 1).

Many Arab countries also experience large demographic flows from rural areas to urban centers, as young men and women abandon tedious agricultural toil for supposedly more reliable, exciting urban employment. Whereas in 1970 less than a third of the Arab region’s population resided in urban areas, today slightly more than half live in cities.By 2050 close to three-quarters of the projected 600 million Arabs are expected be urbanites.

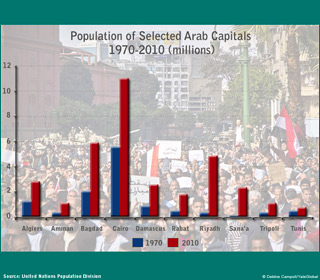

Rapid population growth is evident in Arab capitals such as Algiers, Amman, Baghdad, Cairo, Damascus, Riyadh and Sana’a (Figure 2). For example, since 1970, the population of the largest Arab city, Cairo, doubled from 5.6 million to 11 million; in comparison, London’s population grew from 7.5 million to 8.6 million. More remarkable demographic growth has occurred in Sana’a and Riyadh, which ballooned from relatively small towns of about 100,000 and 400,000 in 1970 to large urban agglomerations of approximately 2 million and 5 million inhabitants, respectively.

Many poorer Arab countries have seen substantial outflows – increasingly illegal – of job-seeking men and women to Europe. Unemployment among young adult Arabs is high, especially in Northern Africa where nearly 30 percent of young adults aged 20 to 24 years are unemployed. In stark contrast are the oil-exporting Arab nations of the Persian Gulf, which have recruited large numbers of foreign workers, intentionally non-Arab, to provide labor for their expanding economies. Foreign workers, especially form sub-Saharan Africa and South Asia, live largely segregated lives from local Arabs, often doing undesirable jobs with pay levels and conditions unacceptable to the native Arab population.

The populations in the Arab region are relatively young, with majorities in many countries aged less than 25 years compared to about 30 percent for the population of more developed countries. One person in every five is a youth between the ages 15 to 24 years. In contrast, European youth account for about 12 percent of the continent’s population.

In a region troubled by persistently high levels of unemployment and underemployment, rapidly growing Arab youth populations face limited job opportunities, especially acute during the recent global economic downturn. Even in wealthy Saudi Arabia, 40 percent of Saudi youth lack productive jobs and nearly half of those who work take home less than $830 a month. Simply accommodating increasing numbers of Arab youth entering the labor force over the next 10 years will require millions of new jobs.

Despite comparatively low levels, the Arab region witnessed the fastest expansion in average levels of educational attainment in the world during the past two decades. Not only did access to basic education become more widespread with an estimated 41 million children in primary schools in 2007, significant gains in enrollment ratios were achieved at all levels of education as well as the progressive closing of the gender gap in formal education. However, the quality of education and its relevance to the job market continue to undercut effectiveness of Arab programs.

Another trend is delayed ages at marriage and family formation. Largely due to increasing education and limited job opportunities for young adults, average ages at marriage have risen significantly. Whereas Arab men and women in the recent past generally married in their early 20s, today they postpone marriage and families to their late 20s or, in some cases, early 30s for men. For example, in Algeria, average age at marriage in the 1960s was about 19 for women and 24 for men; today it’s close to 30 for women and 33 for men.

Among the responses to delayed age at marriage among most Western nations has been an increased prevalence of pre-marital sex and cohabitation. In Arab countries such social arrangements are by and large prohibited and, in more traditional communities, strongly sanctioned, including the use of honor killing. As a result, young Arab men and women go through much of their 20s with limited outlets for companionship and intimacy.

With delayed marriages, increased levels of education, urbanization and calls for gender equality, women increase their participation in the formal labor force and seek greater economic independence and political involvement – changes in stark opposition to traditional notions of an Arab woman’s place in the family and community – marrying, bearing children and tending to domestic chores while the Arab man was traditionally responsible for economic, political and security matters.

Ethnic, religious and tribal demographics compound challenges for Arab countries. In countries, such as Bahrain, Iraq in the past, Lebanon and Syria, religious minorities rule, often with discriminatory policies favoring their own. In other instances, small circles among the majorities dominate the country, often suppressing or ignoring human rights of minority groups.

Another minority in the Arab region is the refugee population. Arab countries are estimated to include about half of the world’s 15 million refugees, including more than 4 million Palestinian refugees. In some countries, the refugees are not permitted to work and are often kept apart – sometimes in camps – from the native population. Rivalry, ill-feeling and resentment between refugees and locals, especially those unemployed, are not uncommon and lead to clashes, as witnessed in Lebanon, Jordan and Syria.

To be sure, there are distinct economic and political differences across the Arab region. Nevertheless, Arab countries have many demographic challenges in common. While not constituting the primary causes for Arab revolution, rapid population growth, the “youth bulge’ and high unemployment rates exacerbate major economic, political and human rights issues that have given rise to recent uprisings sweeping the region.And even though most Arab countries are experiencing the demographic transition from high to low rates of fertility and population growth and related population changes, the demographic momentum from earlier periods of rapid growth will remain a commanding force well into the future, imposing social, economic and political consequences for the projected 600 million in the Arab world by mid-century.

Joseph Chamie, former director of the United Nations Population Division, is research director at the Center for Migration Studies.