Libya Exposes Fault Lines in the Mediterranean – Part IV

Libya Exposes Fault Lines in the Mediterranean – Part IV

LONDON: It was supposed to be a new world order, the emerging powers making their presence felt even as the old and tired West relieves itself of the responsibility to maintain global order. But if the debate on Libya is anything to go by, the new world order resembles the old one – the established powers still try to shoulder most of the responsibility of maintaining global order while the emerging powers shirk duties as global stakeholders.

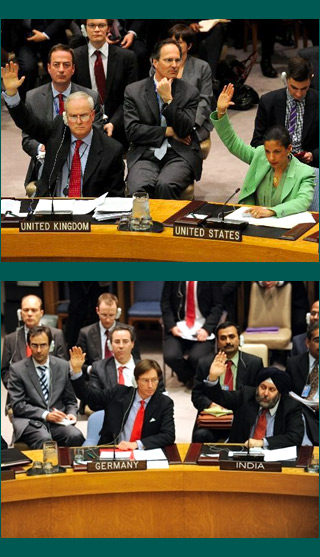

China, India, Russia and Brazil – their rise supposedly underpins the shifting global balance of power – abstained on the resolution authorizing a no-fly zone over Libya and “all necessary measures” for protecting civilians there from Colonel Muammar Gaddafi’s forces. China’s permanent representative to the UN, Li Baodong, argued that his country supports “the UN Security Council’s adoption of appropriate and necessary action to stabilize as soon as possible the situation in Libya and to halt acts of violence against civilians,” but “China has serious difficulty with parts of the resolution.” Vitaly Churkin, Russian envoy to the UN, warned “outside forces” could destabilize the region and described the resolution as “unfortunate and regrettable.” Arguing that Russia did not veto the resolution as it was “guided by the necessity to protect civilians and by general humanitarian values,” Churkin suggested that responsibility for inevitable consequences would be borne by those who resorted to such actions. Russian Prime Minister Vladimir Putin likened the Security Council resolution on Libya to a medieval crusade call.

While expressing her nation’s deep concern and underlining that Brazil stood in solidarity with movements in the region expressing legitimate demands for better governance, Maria Luiza Riberio Viotti, Brazil’s UN representative, noted that the measures contemplated in the resolution went beyond that call and might exacerbate tensions on the ground. India cautioned, “the resolution that the council has adopted authorises far reaching measures under Chapter VII of the UN charter with relatively little credible information on the situation on the ground in Libya.” Worse, India argued, the resolution lacked clarity on “who and with what assets will participate and how these measures will be exactly carried out.” Responding to reports that Libya should be divided, India insisted that the sovereignty, unity and territorial integrity of Libya should be preserved.

These reservations echo the standard policies of these states since the 1990s if not before. China, Russia, Brazil, and India and many others favor a multi-polar world order where US domination remains constrained by other “poles” in the system. They zealously guard their national sovereignty, wary of US attempts to interfere in what they see as domestic affairs of other states, be it Serbia, Kosovo or Iraq. They took strong exception to the US air strikes on Iraq in 1998, the US-led air campaign against Yugoslavia in 1999, and more recently the US campaign against Saddam Hussein, with Moscow, Beijing and New Delhi arguing that these violated the sovereignty of countries and undermined UN authority.

These states tend to share an interest in resisting interventionist foreign-policy doctrines emanating from the West, displaying conservative attitudes on the prerogatives of sovereignty. As such, they have repeatedly expressed concern about the US use of military power around the world – a continuation of the desire of to oppose what a French diplomat had termed US hyperpuissance since the end of the Cold War.

But now the West is in retreat facing an economic onslaught from emerging powers. The case of Libya should have been relatively easy for these emerging powers to navigate. The western response came as the Libyan leader threatened to launch a final attack to push out rebels from Benghazi, the nation’s second largest city. “We are coming tonight,” Gaddafi announced on television, referring to the rebel forces occupying Benghazi. “There won’t be any mercy.”

Fearing a bloodbath, the Arab League called for a no-fly zone to be established in Libya and the resolution, co-authored by Britain and France, was tabled by Lebanon in the Security Council. Members of the Arab League participate in the military operation. Until the last minute, the US remained reluctant to participate, and the western countries showed no appetite for introducing land armies in Libya. UN Security Council resolution 1973 explicitly excludes “a foreign occupation force of any form on any part of Libyan territory,” ruling out deployment of ground troops. Not surprisingly, Ibrahim Dabbashi, Libya’s deputy envoy to the UN who has turned against Gaddafi’s regime, did not share the abstainers' concern, suggesting “it has nothing to do with the Libyan people.”

The debate on Libya once again underlines that, despite the hyperbole about the decline of the West and the rise of the rest, the “rest” are not ready to take on roles as global powers. The emerging powers are yet to articulate a world vision that provides an alternative to the western-designed global order. They have yet to review the concept of sovereignty in a globally interconnected world where a government’s brutal repression of its citizens is instantaneously broadcast around the world, raising questions of moral responsibility for fellow human beings separated by state borders. Opposing every move by the West is easy. Criticizing from the sidelines is even easier. Offering a credible alternative is the real test of global leadership of the rising powers.

The powers approaches differ. In China’s and Russia’s case, abstention actually meant a yes as their veto would have killed any UN action. That they abstained meant that they're willing to let the West proceed against Libya, albeit with limits. Moreover, they're non-democracies, so they can’t be expected to champion democratic aspirations of the Arab street. The actions of India and Brazil, however, underline the real challenges of the emerging global order.

India, despite being the largest democracy in the world, has largely watched events in the Middle East in silence. In many ways, reticence is understandable. The situation is highly unpredictable, and the government takes its time to consider implications especially in terms of energy security. Moreover, for New Delhi to comment on unfolding events would have been hypocritical given how seriously India takes the principle of non-interference in other states' internal affairs. India remains worried about the safety of its nationals who decided to stay in Libya. It’s also discomfited by the “precedent setting” parts of the Security Council resolution. The coming months in Libya may well vindicate the reluctance of countries like India and Brazil to join the anti-Gaddafi coalition.

As a consequence, India and Brazil look most uncertain on the Libyan conflict. No one knows where they stand. This is a time of great tumult in the Middle East, testing the international community's resolve to tackle the region’s most difficult issues. All global powers struggle with tough choices as they try to strike a balance between their values and strategic interests in crafting a response.

But so far, the emerging powers are not ready to answer the tough questions about their global priorities. The BRICs have yet to develop a coherent philosophy on citizen’s rights and role of sovereign states in an interconnected world. By refraining from offering a credible alternative, the emerging powers ensure that the responsibility to protect humans from mass atrocities remains a western responsibility, not international responsibility. Clearly, this is an ineffective approach to deal with issues of human rights and state sovereignty. For all the talk of new powers on the global stage, they'll remain largely peripheral in shaping global discourse and events.

Harsh V. Pant teaches in King’s College, London.