To Lift Afghan Women, Educate All

To Lift Afghan Women, Educate All

EAST LANSING: As NATO troops plan to withdraw from Afghanistan by 2014, the world worries about the country’s stability and especially for Afghan women. On his first trip to Afghanistan in March as US secretary of state, John Kerry pointedly met with Afghan businesswomen at the US embassy in Kabul, fielding questions about security.

Given the brutal track record of the Taliban treatment of women and their violent opposition to girls’ education, the fate of women in post-NATO Afghanistan remains in question. Armies of NGOs spread throughout in Afghanistan, often working alongside the troops, advising and building infrastructure for education and health care. Over the past decade, many Afghans have witnessed an alternative course for the future and wonder if all will be imperiled after withdrawal of protective forces.

How Afghanistan and its women fare depends on the kind of political power and economic opportunities that emerge in the country. One example of the NGO role in preparing women for a new Afghanistan is a tiny college in Arizona, a US state known for its opposition to immigration. Thunderbird School of Global Management recruited women from Afghanistan to attend Project Artemis, an intensive two-week program for entrepreneurs. Students are then paired with US, Canadian or European mentors. For at least two years, the mentors connect over Skype and email for questions and chats with Afghan women who craft soccer balls, embroider clothes and linens, or raise bees.

Early on, at open houses, college officials fielded questions from puzzled Arizonans like “Why are you helping terrorists?” Thunderbird carried on with its small program, securing funding from the US State Department, Goldman-Sachs 10,000 Women, the Australian Agency for International Development, the Business Development Center in Jordan and more. The program has graduated 74 Afghan entrepreneurs who have since returned to their homeland, armed with a training toolkit, in turn training at least 15,000 other Afghan women and men.

Project Artemis is one of many programs reshaping Afghan life: The military sent in female engagement teams to establish relationships with Afghan women and collect information to propose community projects. Provincial reconstruction teams, including NATO troops and civilian specialists, organized projects, technical advice and training in every province in an array of fields.

The US Agency for International Development reports that the US alone trained more than 633,000 men and women in farm and business skills, financed more than 500 health facilities, trained more than 21,000 health providers, including more than 1,700 midwives. School enrollment over the decade grew sevenfold, including 30 percent females, with millions of textbooks distributed. Since 2002, NATO developed internet connections throughout Central Asia, including connectivity for Afghan provinces and 18 universities, as part of its Virtual Silk Highway Progam. Thanks perhaps to women’s education, Afghanistan’s fertility rate has fallen, from 8 children per women in the mid-1990s to 5.54 projected for this year.

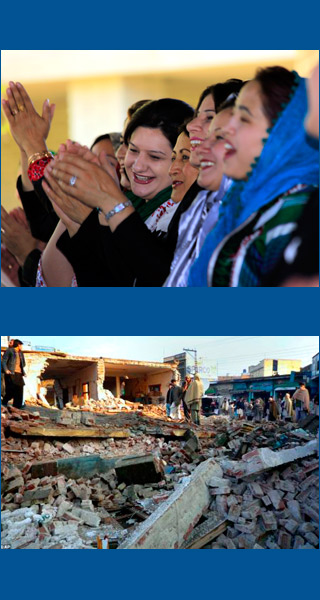

“There’s been a sea-change in the attitudes of women from Afghanistan,” says Wynona Heim, director of Project Artemis Afghanistan. She describes the entrepreneurs as assertive, street smart with their caution, brimming with sophisticated questions. The school distributes laptops to students. Faculty during the first year had to teach students how to turn them on. The most recent class quickly created its own Facebook group page.

Project Artemis requires literacy, but targets disenfranchised women not already enrolled in college. Some students arrive with a few years of basic education.

The setting for Project Artemis – the Thunderbird School of Global Management campus – is itself a product of war. The tiny school was founded in 1946 by a US Army Air Forces lieutenant general. Barton Kyle Yount, in charge of training pilots during World War II, had found American aptitude for global connections wanting. According to the Arizona Memory Project, he obtained the 650-acre military airfield for free from the War Assets Administration with one condition – the base be used as a “school for instruction in foreign area studies, business administration and international relationships.”

Enrollment declined sharply after the 9/11 attacks, but since bounced back. Programs like Project Artemis boosted the school’s reputation, particularly among diplomats and business people in Muslim-majority nations.

Trade and citizen diplomacy are powerful forces, Heim notes. Once in Arizona, the Afghan women are surprised by US diversity. They attend services at a mosque open to women, with worshippers from around the world. When the women return to Afghanistan, others might say “Americans just want to control us” or “Americans don’t like Muslims,” and the women can say, ‘That’s not true,” Heim explains. “It’s why we bring women purposefully from all over Afghanistan – to create a network that can transcend tribal politics, religion, and other barriers.”

With programs in Pakistan and Peru, too, the project encourages cross-border networking. For example, one Afghan woman who makes furniture ships it to a Pakistani woman who does interior design for offices.

Still, obstacles await Afghan business ventures at every turn. Elise Collins Shields, founder of CommonWell Institute International, Inc., at the University of Arizona, trains Project Artemis mentors, has mentored herself and describes one business plan: In Afghanistan, women are seamstresses; men are tailors. Women seeking fittings send along measurements with male relatives to tailors. So, one woman set out to train women as tailors. The community lacked reliable electricity, so mechanical sewing machines were donated. She turned her home into a school, but had no tables. Women sat on the floor, pumping treadles. Lack of heat forces winter closures.

Security is a constant worry, accounting for more than one third of business costs, by some reports. Project Artemis entrepreneurs report receiving threats after returning home, and Heim explains the women must be flexible: Some close their business and start another with a lower profile; some work from home or take a job. The school has lost contact with about 10 percent of its Afghan graduates.

Security fluctuates in the diverse country. Some areas report minimal violence; other communities are described as treacherous. The United Nations reported a drop in civilian casualties for Afghanistan in 2012, yet a 20 percent rise in deaths and injuries of women, attributed to domestic violence and culture, according Jan Kubis, UN special envoy to Afghanistan.

With up to 600,000 jobs needed annually in a country where more than 60 percent is under age 25, unemployment is as much a threat as insurgency, suggests Wais Ahmad Barnak, Afghan minister of Rural Rehabilitation.

Crime reports from Pajhwok Afghan News since the start of March show a pattern of schools and police as targets, including teachers gunned down in Balkh, beheadings of local security in Badghis; the bombing and assault on a crowded courthouse in Farah that left 54 dead and 100 wounded; a suicide attack on a convoy delivering textbooks to schools in Zabul Province, which killed US diplomat Anne Smedinghoff, 25.

Education and security ensure progress. After Ambassador Kolinda Grabar, NATO Assistant Secretary General for Public Diplomacy addressed three Afghan universities on International Women’s Day, one student spoke up: “If we do not educate the men, how can we expect them to send girls to schools?”

Women who have tasted freedom from obscurantism are a force for change, but their success, indeed survival, depends on how many of their male cohorts accept women outside the home, let alone in workplaces. A relative small number of Taliban fighters, perhaps 35,000 in all, are fighting progress, and great courage is required of the Afghan people.

Susan Froetschel is the author of Fear of Beauty, a suspense novel about women in a fictional Helmand village who fend off extremists.