Lonely at the Top

Lonely at the Top

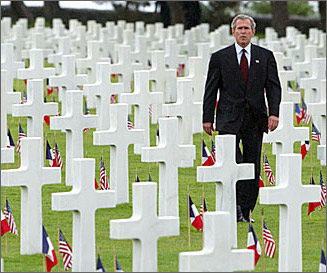

WASHINGTON: Nothing perhaps says more about how the world has changed since Sept. 11, 2001 than the isolation in which the US finds itself today. It seems more like ages ago since students in Iran were holding candlelight vigils for the victims of the Sept 11 attacks and the Europeans unanimously voted to consider the attack on the US as attack on all NATO members.

With American casualties in Iraq mounting and weapons of mass destruction remaining elusive, Deputy Defense Secretary Paul Wolfowitz told Congress recently that he is suspicious of United Nations offers of help because they might entail some constraints on US actions. The latest US call for UN support in Iraq should not be misunderstood – help is welcomed, but only on American terms, and only so long as Washington retains ultimate control over Iraq's reconstruction.

Americans have been wondering why the world has not rallied to our side in the last two years on problems from Iraq to North Korea, and our leaders have provided convenient answers. "They hate our freedom" or "they envy our success" or "criticism just goes with the territory of being the top dog," we are told.

Glibness, however, requires gullibility.

Take first the very notion of America battling alone in the face of envy and hatred. The outpouring of sympathy and support that occurred around the world on Sept. 12, when even the French newspaper Le Monde proclaimed "We Are All Americans" should have put that notion to rest. If it didn't, certainly the number of world leaders, from India to Canada, backing UN Secretary General Kofi Annan in his offer of help in Iraq showed a worldwide willingness to help with reconstruction, even though most nations had opposed the war.

The real problem here is not so much foreign hostility as America's insistence on going it alone in its own way. Wolfowitz's testimony is the tip-off. The United States would rather be in absolute control than accept any help that might in any way dilute that authority or that might even slightly complicate US operations.

This was evident in the case of Afghanistan long before the Iraq question arose. Immediately after Sept. 11, America's longtime allies in NATO literally begged Washington to include their troops in the invasion of Afghanistan, to no avail. It would be easier and faster simply to move alone, the Pentagon said.

The lack of interest in NATO and UN help is the natural result of the adoption by the United States of the radical new doctrine of preventive and pre-emptive war developed by Wolfowitz and a small group of self-styled neo-conservatives after the collapse of the Soviet Union in late 1991.

Although the US won the Cold War with a strategy of deterrence, and by building alliances and multilateral institutions such as NATO, the UN and the World Trade Organization, the new thinking argued for military superiority such that no other power would even consider a challenge. In foreign policy, this thinking also demanded a unilateral approach, based on the view that while friends are nice to have, they're really not necessary for the US to achieve its objectives.

Much discussed and partly adopted during the 1990s, this doctrine of pre-emption and "coalitions of the willing" in place of deterrence and alliances became the foundation of US strategy after Sept. ll. In the world of the 21st century, it was argued, the threats will be so dire and immediate that we must be prepared to strike first, and perhaps alone, to avoid being struck.

Of course, to be credible as something other than an excuse for permanent war, such a strategy must be based on accurate intelligence about the immediacy and seriousness of the threat.

In the run-up to the recent Iraq war, the Bush administration repeatedly emphasized that Iraqi dictator Saddam Hussein had large numbers of weapons of mass destruction that could be unleashed against the United States at any moment. Other countries harbored doubts, but, claiming superior knowledge as well as virtue, the United States overrode allied requests for further investigation and deterrence and set course for war with a "coalition of the willing."

In the aftermath, we have learned not only that our intelligence was faulty, but that while we can win the military battles by ourselves, we really need help with what comes afterward. Yet our doctrine and operating style inhibit us from getting that help.

Despite our great power, it is clear that beyond the battlefield there is little that we can accomplish by ourselves in an increasingly globalized world. We can't fight the wars on terror and drugs by ourselves, nor can we run the world economy or deal with epidemics such as AIDS and SARS, or problems like global warming, by ourselves. We need help and friends, yet our inconsistent attitudes and policies are a source of constant disappointment to those who would be our friends.

Examples of this recurring problem can be found from South Korea to Afghanistan, but perhaps the most troubling example of American inconsistency is international trade. During his recent trip to Africa, Bush talked about helping fight AIDS and promoting investment and economic development.

But like all of his Republican and Democratic predecessors, he failed even to suggest the one thing that would make all the difference. Despite all of America's rhetoric about the glories of free trade and all its pressure on countries like China and Japan to open up their markets, American leaders never suggest cutting subsidies for US agribusiness. Consider that, in West Africa, farmers using oxen and hand ploughs can produce a pound of cotton for 23 cents while in the Mississippi Delta it costs growers using air conditioned tractors and satellite-guided fertilizer systems 80 cents a pound. Logically, the US farmers ought to be switching to soybeans or something else they can grow more competitively. Instead, they are expanding their planting and taking sales away from the African growers in export markets. How can they do this? Via subsidies to the tune of $5 billion. Not surprisingly, Muslim West Africa does not see America as a friend and force for good and is increasingly listening to the mullahs who call America the "Great Satan."

Thus does America checkmate itself by eschewing offers of help and insisting on total control while alienating those who would be friends by talking the talk but not walking the walk. It should be clear by now that the doctrine of pre-emptive war and coalitions of the willing can no longer be maintained. The failure to find those weapons of mass destruction in Iraq means that future US warnings of imminent threats will be met with disbelief by the rest of the world and the American public.

Moreover, it is clear that the United States is already stretched to the limit by the effort in Iraq and could not contemplate any significant additional interventions without real help from the international community. But others will not proffer this help without getting some say in the policy-making process.

Thus, the way forward is to return to the multilateralism that won the Cold War, and to work on correcting our inconsistencies rather than telling ourselves it doesn't matter what the rest of the world thinks. In fact, it makes all the difference, because, in the shrunken world of the 21st century, we won't be able to achieve our objectives without friends.

Clyde Prestowitz is president of the Economic Strategy Institute and author of “Rogue Nation: American Unilateralism and the Failure of Good Intentions.”