The Markets Prey on Debt-Laden Nations

The Markets Prey on Debt-Laden Nations

SINGAPORE: Select reported figures on growth show improvement, yet global recovery seems as elusive as ever. The US, the eurozone and Japan still show disappointing growth, and the three have something in common: All are mired in debt, sucking their capabilities and constraining their efforts at remedial measures. Until the West finds a way out of its stifling and growing debt, genuine recovery is out of reach.

Some regard the financial markets as a culprit, but this is the wrong approach, suggesting misunderstanding about how the market functions and reacts. The markets are governed by selfish behavior, focused on financial gains. Markets care about politics only to the extent they affect profit-making ability. The markets analyze behavior and draw conclusions – to earn money!

The omens for 2011 are not good. The year starts with a toxic cocktail of nervous investors scared by debts and deficits, excess liquidity nourished by the US Federal Reserve System, and financial institutions stoked by this liquidity and chasing profits. This is a recipe for instability, ill-founded decisions and reckless behavior. The global financial system lacks steering. No leading institutions point the way ahead, marshalling market forces for a course other than profits.

The market neither supports nor rejects the euro, but smells gains if the eurozone can be broken up or weaker member states forced into default, thus forcing higher interest payments on loans. The eurozone responded reasonably well to the attacks, though the authorities were mostly behind the curve, raising doubt about their abilities despite the political will.

Sensing that battle over the euro is yet not won by either side, the market can be expected to renew its attack before the end of summer, testing the resilience of eurozone member states. The potential profit by driving down bond prices, keeping them low, thereby augmenting the cost of borrowing for deficit countries remains attractive. During late 2010, institutional investors such as pension funds were unwilling to purchase bonds issued by weakest eurozone members, thus letting more speculative institutions control the game.

A combination of reform, austerity, slightly falling euro values and modest growth that’s sustainable will carry the eurozone through for now, giving it breathing space to implement stronger fiscal coordination. Speculators may make life uncomfortable, but as long as the European Central Bank, strong countries like Germany, and weaker ones like Greece, Ireland and Portugal do not lose their nerve, the speculators – irrespective of enormous funds at their disposal – cannot squeeze a sizeable profit out by hammering the eurozone.

So attention will turn to where profit is possible with lectures on debt and that’s the United States.

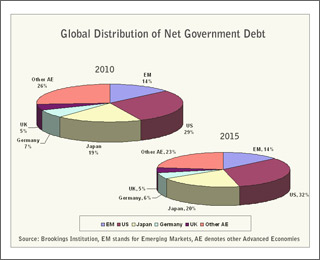

The debt/GDP ratio for the eurozone stabilizes around 85 percent, but continues to rise for the US, anticipated to break the record set at the close of World War II – 109 percent – before 2020. According to the US General Accounting Office and the Congressional Budget Office, taking into account likely policy changes, the federal debt continues to rise, reaching 200 percent around 2030. The federal deficit may improve slightly in the short term, but will balloon again by 2015, as baby boomers retire and social security payouts climb.

Federal debt is not the only US problem: 48 of 50 US states had shortfalls in fiscal 2010 and anticipate more in the years ahead. Stimulus funds distributed to the states under the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act will be spent before 2012. The possibility is real of one or more states going into default and sharply curtailing education, health, transportation programs. Turning to major US cities, the outlook darkens: More than 100 American cities face soaring debt and bankruptcy, including New York City, Detroit, San Francisco and Los Angeles. Combined, US states cities confront a $2 trillion mountain of debt. Incidentally, the year 2010 recorded the largest number of bank failures since 1992.

Economists have theorized just how much fiscal tightening the US needs to reduce the federal debt/GDP ratio to 60 percent. One calculation – made before the extension of the Bush tax cuts – is an annual effort of 2.8 percent before 2020, amounting to a total of 22.4 percent, in tax increases or program cuts, or a combination of both. By comparison, the tightening required of Greece is similar, 3.0 percent annually for a total of 24.9 percent. Unlike the US, which boosts its deficit to higher levels, the Greek government has already introduced measures to reduce the deficit. The rating agencies, consistently wrong in recent years, allegedly contemplate downgrades for France and Spain. The annual fiscal tightening required for these two countries to achieve 60 percent is 1.8 percent for France and 1.7 percent for Spain – less than two thirds of what the US needs to do.

To restore the global economy, debt restructuring must take place, pitching the creditor nations like China against the US and other debtor countries in a tough fight of burden sharing. History suggests the debtor often loses, so it would be wise for the US to contemplate what China will ask for and what the US can and will offer. Secretary of State Hilary Clinton has few illusions, as noted to former Australian Prime Minister Kevin Rudd, according to a leaked cable, “How do you deal toughly with your banker?”

The US has one card up its sleeve. China does not want a weakened US, certainly not with low growth patterns for the rest of this decade. The US market remains valuable for Chinese exporters though talk of China’s dependence on its US exports is off the mark – with net exports accounting for less than 25 percent of Chinese growth as an average over the last five years. The US could offer the quid pro quo prospect of a global recovery for restructuring US debt. Already China is helping stabilize euro-zone by extending credit to Greece and promising help to Portugal and Spain.

The US must admit how its debt has weakened its global role, making it dependent on other countries and undermining its ability to lead.

For China, an equally difficult barrier is realization that dependence on the global economy requires responsibility.

For the eurozone, the crisis is a wake-up call that the US can no longer automatically be counted upon to support Europe. Europe must undertake what will be agonizing reappraisal of its global role.

Around the world, some will initially express glee at the prospect of seeing the US served the same medicine it has forced upon other countries. But that’s shortsighted, overlooking how much the world still needs the US.

The debt problem, in particular US debt, is one more sign that the established world order of the late 20th century is fading. And if not dealt with promptly, the debt problem could bring world order down crashing.

The US and Europe may still initiate a new world order, but only by putting their own house in order and realizing that neither the global financial system nor control over global natural resources are exclusively in their hands. Power and influence must be shared. Otherwise creditor countries will do it their way.