Mixed Blessings of the Megacities

Mixed Blessings of the Megacities

HONOLULU: All the demographic data point ineluctably to the 21st century emerging as the urban century. But evidence also indicates that a vast portion of the new "megacities" – the largest of the world’s cities – will be infested by 19th-century-style poverty. And therein lies one of the most difficult challenges to globalization.

For the first time in human history, more people live in cities than do not. The high rate of urbanization in the past thirty years is due in large part to globalization’s economic impacts on national economies. A paradox of global development exists within these rapidly forming urban aggregates: some residents live at the cutting edge of the 21st century and its abundant wealth, while others reproduce impoverished economic and social relations typical of 19th century Euro-American industrial development.

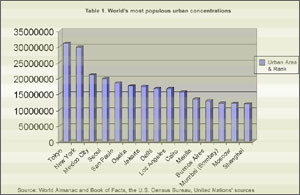

Fifty years ago, 30 percent of the world lived in urban settings; ten years from now, that number will approach 60 percent. In the year 2000, the world supported 411 cities with more than one million inhabitants. Up to the late 20th century, the majority of the world’s urban population lived in Europe and North America. In this century, the largest share will accrue to Asia.

Migration and demographic change combine to produce the megacities. Cross-border migration, both legal and illegal, meets a large part of globalization’s labor needs. Older core cities like Los Angeles, New York, and London have been remade from cross-border migration. Migrants supply labor to the bottom tier of manual work (e.g., Los Angeles' famous day laborers who gather for morning "shape ups" on the corners of shopping centers) and services to the affluent (nannies and housekeepers from Zurich to Washington, DC, to Hong Kong). Increasingly, cross-border migration also involves skilled labor. For instance, nurses and doctors from the Philippines, motivated either by the hope of achieving permanent migration status or earning money to send home, are willing to work at the bottom of wage scales. The Philippines alone has over 8 million migrant workers distributed throughout the world supporting an officially sanctioned governmental remittance economy.

It is primarily intra-country migration, however, that is remaking world settlement patterns. The cities of the developing world pull workers from the countryside into urban settlements at unprecedented rates. This migration is most advanced in China, though it is often overlooked by the rest of the world since it does not involve border-crossing. Yet China currently is engaged in the greatest migration in the history of the world, far outstripping those of the Western world in previous centuries – and it is occurring at a more rapid pace. An estimated 150 million people have already migrated to cities in the last decade, leaving behind an agricultural labor shortage of stunning proportions. Increasingly, only the old and the very young remain to provide agricultural labor. In the early stages of this migration, most people sought work in the larger cities of their regions; more recently, floods of migration are swelling the megacities of Shanghai, Beijing, and Guangzhou, even as other larger cities are emerging.

Throughout the world, the rural poor flock to cities as the only practical solution to endemic rural poverty. National governments support intra-country migration for the urban economic development it supports. Mexico City, Sao Paulo, Taipei, Seoul, and Yokohama are older industrial and commercial cities that have exploded into global production centers built largely on migratory growth. Other cities – Lagos, Cairo, Mumbai (Bombay), Lima, Buenos Aires, Bangkok, Shanghai, Shenzhen-Pearl River Delta, Manila, and Jakarta – owe even more to their magnetic pull of labor from the agricultural sector into contemporary globalized industries in transportation, communication, manufacture, finance, and the like.

Japan, as an early globalizing society in the 1960s and 1970s, populated its immense urban concentrations primarily from urban-rural migration. As one of the most rapidly aging societies in the world, Japan now finds itself with a highly urbanized population, below-replacement fertility, and "shortages" in younger demographic cohorts. Businesses worry about who will do the work in the next decade, and the government worries about who will take care of the elderly. The migration-wary society finds itself pursuing various policies, such as encouraging return migration of diaspora Japanese from Sao Paulo. This pattern will visit other older core industrial cities as they, too, age.

These massive cities at the heart of the economic, financial, and commercial integration characteristic of globalization are simultaneously centers of concentration for world wealth and arenas of despair for hundreds of millions.

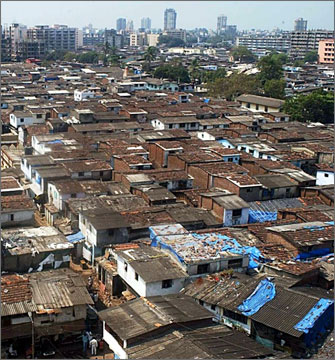

Cities struggling to cope with extremely rapid growth are often strained to the breaking point, unable to provide minimal essential services and infrastructure. Within many global urban aggregations one finds vast slums where provisions of water, sanitation, and electrical power barely exist. These areas are in stark contrast to the "golden centers" that house new financial and commercial enterprises, government, and business elites. Public health and healthcare are woefully inadequate; in many places they do not exist at all. In Latin America and Africa, refugees from war and civil disorder form a special category of urban migration: the disposed, the poorest of the urban poor.

The rapid pace and massive extent of urbanization have taken many governments by surprise. Ill-equipped and often corrupt bureaucracies have little hope of sorting through the range of challenges and problems urbanization presents. The majority of areas that boast appropriate government planning, regulation, and investment are likely within city centers where new building complexes house financial, manufacturing, commercial, media, and transportation elites.

In large areas of urban aggregates, extensive slums hardly experience the touch of government at all. But the consequences to government are significant. In some areas, formal governmental power ceases to exist. Local gangs and militia provide what passes for law and order. The wealthy protect themselves with elaborate security (ironically drawn in part from the inexpensive labor reserves of the urban aggregate), while the poor are subject to the capricious decision-making of local informal authorities.

The results for the less advantaged are not hard to imagine. Without effective, formal government the entire concept of rights disappears. Jim Yardley reports in the September 12, 2004, New York Times on the crass exploitation of labor in urban China, where migrant workers involved in construction (much of it government authorized) are owed $43 billion in back wages, some for as many as 10 years' worth of work.

The policy agendas for these cities are formidable. It is critically important that national governments grant the megacities governance powers equal to the tasks they face; the ability to effectively regulate will be critical to establishing a better functioning civic order. Within the range of new regulatory power must be included powers to tax, retain revenues, and hire sufficient personnel to provide needed infrastructure and order. Nation-wide support for local anti-corruption policies is a requirement of the first order.

This new urban world stands at the center of the inequalities that are so much a part of contemporary globalization. After two decades of development, the United Nations finds that 2.8 billion people are poorer than they were at the beginning of this period. The first urban century has its work cut out for it.

Deane Neubauer is executive director of the Globalization Research Network (GRN) headquartered at the University of Hawaii, Manoa www.globalgrn.org. Neubauer is also professor emeritus of political science at UHM.

Comments

Excellent!