Modi’s Success in India’s Elections: Five Factors

Modi’s Success in India’s Elections: Five Factors

NEW DELHI: The Bharatiya Janata Party, BJP, in power since 2014, surprised the world – and perhaps even itself – with decisive victory, obtaining 303 of 545 seats, with 37.4 percent of the votes, increasing its parliamentary tally by 21 seats. Its main opponent, the Congress Party, remained a distant second, winning 52 seats – a stable 19.4 percent vote share.

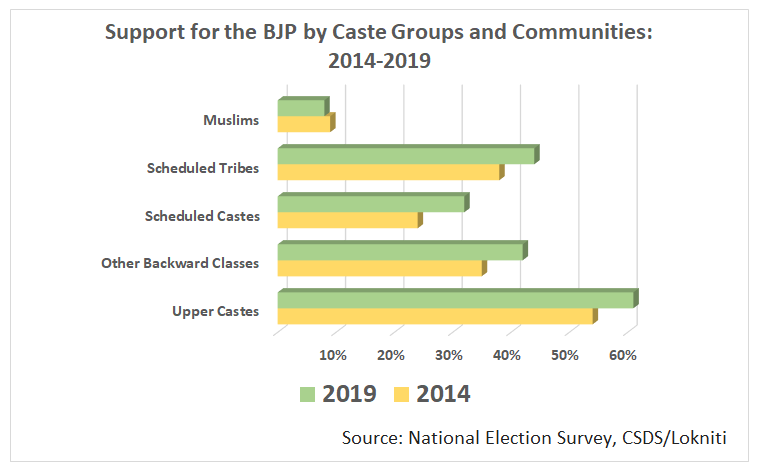

The BJP thus repeated its 2014 performance, in which it swept the northern and western regions, and made inroads into new states, where it did not have a traditional presence, including 40 percent of the votes in West Bengal and nearly 40 percent in Odisha. The BJP also expanded its vote base considerably, particularly among non-elites. These figures help the BJP uphold a narrative of Hindu vote consolidation for the party. The BJP fielded five Muslim candidates in 2019, none of whom won.

Prior to polling, a series of factors should have hampered the BJPs prospects: tepid growth, economic slowdown and a growing crisis of joblessness, especially among the youth, estimated in March by the Mumbai-based Centre for Monitoring the Economy at 13.2 percent of all recent graduates, with a positive correlation between unemployment rate and education level. Over the past few years, jobless growth and shocks to the economy, such as the 2016 demonetization – in which the government wiped out 86 percent of its currency in circulation overnight – disrupted an already ailing agrarian economy, precipitating thousands of farmers to protest across the country. This rural distress was cited as an explanation for the string of defeats that the BJP suffered in December 2018, ahead of the general elections, in the assembly polls in the states of Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh – all traditional strongholds.

Yet, six months later, districts that had once firmly rejected the BJP turned out with staunch support. The BJP scored its highest vote share in the areas struck hardest by the rural crisis.

At least five main factors contribute to BJP’s turning the tables:

The first is the personal appeal of the prime minister, who enjoys popularity levels rarely seen in the most effective democracies. According to the CSDS survey, one third of BJP voters declared they would have voted differently had Modi not been the prime ministerial candidate. He led a hyper-personalized campaign, projecting providential qualities: protector of the poor through welfare schemes bearing the prime minister’s stamp and protector of the nation through an aggressive posture vis-à-vis Pakistan.

On February 14, a deadly terrorist attack against paramilitary forces in Pulwama, Kashmir, in which at least 40 men died, and quick Indian retaliation in the form of airstrikes in Balakot, on Pakistan territory, created an opportunity to lead a campaign centered on national security and the prime minister’s projected decisiveness. Breaking with tradition, the BJP used the armed forces as a campaign subject, before the Election Commission moved to stop the practice.

Second, the BJP campaign strategy was backed by the most formidable election campaign machinery assembled by any party in India since independence. The party formed campaign cells in more than 80 percent of the million polling booths set up for the election. It appointed one panna pramukh, or “sheet leader,” for every 200 voters registered on the electoral roll. It built an organizational pyramid, connected but distinct from the party organization, that covered all the seats it contested. The BJP also benefited from the involvement of thousands of volunteers from a constellation of parent Hindu nationalist organizations, referred to as the “Sangh Parivar.” These volunteers and campaign staff had access to lists of millions of beneficiaries of central welfare schemes for electoral targeting.

Third, the BJP led a blitz campaign aimed at saturating traditional media with the prime minister’s image. By March, the BJP had purchased 53 percent of all media space, across print and electronic media, versus 14 percent for the Congress. It also dominated social media, both mobilizing foot soldiers by drawing on the Namo App, launched in 2015 as a one-stop shop for all BJP social media campaign material, and reaching out to voters via thousands of Whatsapp groups. The Election Commission put restrictions on a television channel launched in March – NaMo TV – and a biopic of Modi scheduled to be released on the eve of the first phase of polling.

The BJP thus controlled much of the media and social media space, enabling it to reach out to electorate segments while selectively using a discourse from an arsenal comprising national security, providentialism and welfare, as well as religious majoritarianism. The BJP used religious appeal to address its core base of supporters while projecting the prime minister’s image as protector or sentinel, both at home and abroad.

These three aspects of the BJP’s campaign were sustained by unprecedented levels of campaign expenditures. The Delhi-based Centre for Media Studies estimates that campaign expenditures crossed $7 billion, making it the world’s most expensive election to date. While these figures are unverified, and unverifiable given the lack of transparency in India’s electoral funding, it is estimated that the BJP concentrated 93 percent of corporate donations between 2016 and 2018, reports the Association for Democratic Reforms. The BJP also benefited from the bulk of electoral bonds purchased during the two months preceding the results. Citizens or companies can purchase and transfer bonds to parties as a donation. The bonds remain active for 15 days, and while donors must register details with banks, the names are kept confidential. These funds helped the BJP to craft a larger-than-life figure for its leader and deploy a campaign that no other competitor could match.

A fifth factor came from the opposition – weak, fragmented and disorganized. The Congress and many regional parties failed to form a consolidated alliance or find tone and content for their campaign. They watched from the sidelines as the BJP’s juggernaut of a campaign unfolded.

There are lessons for the future. First, the 2019 results confirm that the 2014 BJP victory was not an aberration, the product of circumstances combining the rise of a providential leader and rejection of a 10-year-old corruption-ridden regime led by the Congress. The 2019 outcome shows deeper transformational trends at work and, while one cannot infer that every BJP voter adheres to its Hindu majoritarian agenda, there is no doubt that majoritarian ideas and ethno-religious nationalism have found greater traction in India. The presidentialization of politics in India was backed by an effective mix of welfarism, a militaristic posture vis-à-vis Pakistan and widespread use of religious nationalism tropes.

Since May 23, attacks against members of India’s largest minority – Muslims – have multiplied. Nearly 50 lynchings and many instances of assault or public harassment have occurred, mostly unchecked, as detailed by the Violence Lab from the Polis Project. By denying Muslims representation, the BJP has sent the signal that the public sphere belongs to the majority, emboldening local militant organizations and individuals to act on discriminatory beliefs.

The BJP performance is not backed solely by such ideas – far from it. In fact, the BJP’s strength lies in its ability to mobilize on a variety of registers, including those of hope and aspirations. In this sense, the BJP wave differs from most other right-wing populist waves and figures that tend to display majoritarianism and prejudice without a mask – as well as need to satisfy the world’s largest pool of voters who expect tangible achievements.

Gilles Verniers is assistant professor of Political Science and co-director of the Trivedi Centre for Political Data, Ashoka University. He expresses his personal views in this essay.