Mongolia in Globalization’s Chokehold

Mongolia in Globalization’s Chokehold

ULAAN BAATAR: It’s been 20 years since I’ve been in Mongolia, the large country of high desert plains sandwiched between China and Russia, and much has changed. Some, education and food supply, is for the better, and a lot – including urban sprawl and rising inequality – is for the worse. Much of the change has to do with globalization.

In 1992 Mongolia had just been liberated from communism. The Soviet system provided social services, but eviscerated the traditional Tibetan Buddhist culture and left little room for democratic participation.

At that time democracy was in the air. A dean at the National University of Mongolia asked how American professors elected the presidents of its universities, since they would like to copy the model. Sadly, I had to tell him that US university administrators were appointed, not elected, and he seemed surprised.

Downtown Ulaan Baatar was quiet and staid then. The rows of faceless stolid buildings had a certain socialist institutional charm. The main hotel was a grand affair in Soviet style meant to host visiting dignitaries from Moscow, but a modern hotel was under construction several blocks away. Change was on the way.

Twenty years later, I stayed in that once-new hotel, the Chinggis Khaan, named for the great leader of the vast 13th century Mongol Empire, but it was already looking a bit seedy, its elegance fading. Even the statue of the great Khaan looked a bit worn.

Much can be said of the rest of the city. It’s now swelled to twice its size in 1992. Almost a million and a half people live in the crowded valley, and Ulaan Baatar embraces almost half of Mongolia’s total population.

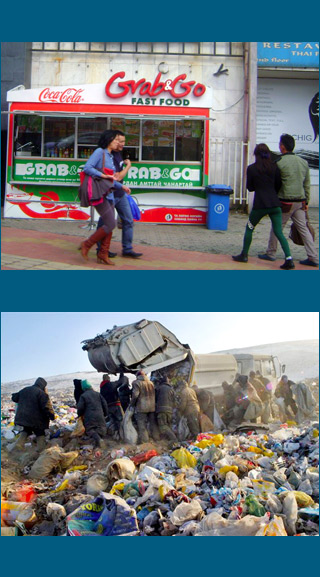

Most seem to have cars. The roads are packed, the honking, pushing vehicles edging over streets that appear not to have been maintained since socialist days. Shops have been constructed in front of the Soviet-style apartment buildings, their gaudy signs advertising everything from food marts to massage parlors.

Quite frankly, the city is a mess. The urban sprawl has taken up the surrounding valleys with huge encampments of low-waged workers living in traditional gers, or yurts, with no amenities. The combination of exhaust fumes from the vehicles, woodstoves and billowing smoke of three enormous coal-burning power plants has created among the worst smog in the world.

Mongolia’s recent changes are due, in part, to rapid economic development and demographic shifts that affect societies in transition at any time in history. But they’re also due to a more recent phenomenon, accelerated globalization.

On the plus side, globalization has raised the living standard of most urban, educated professionals who now live in high-rise apartments with plasma-screen televisions rather than sleeping in the dark in crowded, canvas-draped gers. Cell phones are everywhere. Even in the Gobi desert I saw goat herders and camel drivers chatting away, attempting to round up lost goats, which I regard as a great use of modern technology. College students are addicted to Facebook and Twitter.

A kind of Mongolian pop music combines a modern beat with traditional sounds, along with Justin Bieber. American DVDs are everywhere, and basketball is a national obsession. One sporting goods shop is named for Michael Jordan.

The quality of food has improved enormously. In the early 1990s, offerings were limited to various kinds of meat, usually overcooked mutton – a nightmare for an American vegetarian. The city now has four vegan restaurants, frequented by health-conscious young Mongolians. Vegetables are easily available, although they – like most everything else – are imported from China.

Most young professionals are reasonably comfortable. If they can avoid the roads, most probably feel that globalization is a good thing.

There are, however, two areas in which globalization has played a darker role, having to do with unbridled capitalism and political corruption. And the two are related.

When Mongolia opened up to the world after the fall of the Soviet Union in 1990, it also opened itself up to new investment, especially in its vast stores of mineral wealth. A $5 billion dollar copper and gold mine is being constructed at the rich Oyu Tolgoi deposit in the Gobi desert, and a new rail line is coming from China. The plundering of Mongolian resources is moving at a breakneck speed.

Mongolians receive cash for this exploitation, of course. And it’s easy to see where much of the money has gone. I counted six Lexus SUVs and two Hummers one evening while stuck in a traffic jam. Hermès and other luxury stores crowd the downtown area, and fine dining is available on rooftop restaurants. Gleaming new hotels eclipse the elegance of the Chinggis Khaan Hotel. Gated estates have emerged in the foothills east of the city.

It’s also easy to see where the money has not gone. As bad as the city’s roads are, in the countryside they collapse into muddy ruts. The main highway, the east-west trunk road, is one of the few that’s been paved but it’s already full of potholes. Most other roads are dirt trails across the plains.

Money is not going into social services either. The end of the socialist system also ended free health care, university education and guaranteed jobs. The masses of ger camps surrounding Ulaan Baatar are filled with the underemployed. In the countryside, people still live, as they have since the time of Chinggis Khaan, in gers alongside their goats, yaks and camels.

The government should be gaining from the resource development, and it does exact fees for licenses and mining operations. But where the money goes is a matter of contention.

One of the country’s most prominent politicians, N. Enkhbayar, has been convicted on corruption charges and is serving prison time. He was accused of lining his pockets with bribery money and absconding with payments for mining rights. Even his supporters acknowledged the corruption. But all politicians were, they added, and he was no better or worse than the rest.

The hopes for democracy, when 20 years ago deans wanted to know how to elect their university president, have been replaced with patterns of crony capitalism. The university president is appointed by the Ministry of Education, and some claim that the choice can be influenced by a substantial bribe.

What happened in Mongolia has happened elsewhere in the world in the post–Cold War era of globalization. Two political systems have merged, and the Mongolian case exemplifies the worst features of both.

In the West, exploitation was tempered by democratic control, what theologian and intellectual Reinhold Niebuhr called the “countervailing power” of labor unions and government regulation. In Communist counties the autocratic rule of a managerial society was tempered by an ideology of social service and equality.

Today we see the merger of managerial socialism without the socialism and democratic capitalism without the democracy. It’s the emergence of a managerial capitalism, a system with few checks or balances or controls.

Today’s Mongolia demonstrates a trend found in other post-socialist countries and promoted in the political ideologies of American and European right-wing parties – a managerial capitalism bereft of democratic moderation or social aspiration. What it means for Mongolia, and for much of the world, is a future with plenty of cell phones, Facebook users and Lexus SUVs, but also with brown air, bad roads and astounding economic inequality.

Mark Juergensmeyer is professor of sociology and global studies and director of the Orfalea Center for Global and International Studies at the University of California, Santa Barbara. He is author of more than 20 books including Global Rebellion: Religious Challenges to the Secular State.