Move Over US Soaps, Telenovelas Seduce the Globe

Move Over US Soaps, Telenovelas Seduce the Globe

WASHINGTON: In the 1930s when American detergent companies began sponsoring radio dramas and later television serials aimed at housewives, little did they know how much these “soap operas” would influence the world. For generations of viewers, serials like “Guiding Light” and “As the World Turns” shaped opinions of life in capitalist, democratic societies. But for many reasons, American soaps faded, ceding place to telenovelas from Mexico and Brazil that cast a spell on viewers around the globe.

Audiences for daytime shows have shrunk in the US since the 1980s, as the number of channels increased and more women entered the workforce.

By relegating soap operas to daytime television and female audiences and resisting changes to a formula that worked during the 1950s and 1960s, the US could inadvertently relinquish a hefty, if unintentional, tool in its soft-power arsenal. Soft power, broader than propaganda or popular entertainment, entails a nation’s ability to change attitudes and achieve policy objectives through cultural and moral force, explains Joseph Nye, the Harvard professor who coined the term in 1990. “Seduction is always more effective than coercion,” he notes.

Rather than update the genre, US networks gradually replaced soap operas with news and talk shows, which don’t hold up well for export markets and newcomers to the culture. A decade ago, Chinese women arrived at Yale, crediting hours of soap-opera videos for their proficiency with English, and one detailed the allure for students of the English language: Action is minimal; sentences are short. Props support easy, repetitive chatter about relationships, shopping, family or work routines. Fast-paced news and talk shows include plenty of polarizing drama, but lack the formula for learning languages so cherished by the Chinese student.

New episodes of US soap operas have dwindled in number, and young viewers bypass reruns, seeking latest advice on fashion, hairstyles and slang.

Soon after the US packed daytime TV schedules with soap operas, directors in Mexico, Brazil and Colombia tweaked the formula, shifting shows to prime-time evening hours, limiting series to a year and providing definitive conclusions. These changes, delivered in Spanish, immediately boosted exportability of what became known as telenovelas throughout Latin America and reduced dependence on US programming. Now, Latin American telenovelas dominate airwaves in the Middle East, Eastern Europe, Africa and the homes of US Hispanics.

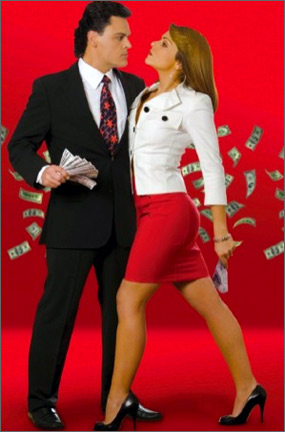

The top-rated show for US Hispanics in May was Univision’s “Hasta que el dinero nos separe,” or “Until Money Do We Part.” The show, originated in Colombia and remade for Mexico, follows a salesman who works off a debt to a car-dealer executive after an accident, then falls in love. Watched by more than 4 million US households, the show leads weeknight slots in Nielsen national ratings for US Hispanics in May. Univision’s Los Angeles station, KMEX-TV, is ranked the top station in the nation among adults aged 18 to 49, and other Spanish-language stations are no strangers to drawing top ratings, from Hispanics or non-Hispanics, in Phoenix, Houston, Sacramento and other US markets.

So even as the US government limits broadcast station licenses for foreign corporations – to no more than 20 percent of capital stock or 25 percent of control – US Spanish-language stations rely on networks in Mexico and elsewhere in Latin American for the bulk of prime-time content, particularly some telenovelas that run five days per week. Many are rags-to-riches tales, focusing on single romance. Directors shoot episodes at the last minute, monitoring audience reactions and adjusting plots.

By comparison, US soap operas are staid, covering extended families of professionals like doctors and lawyers, in 30-minute segments on weekday afternoons. The never-ending tales span decades, discouraging entry of younger viewers and providing one theory for audience decline. The latest casualty is “As the World Turns,” on air for 54 years despite steadily declining ratings since the 1970s. CBS broadcasts the last episode in September.

Directors of both soap operas and telenovelas devise outlandish plot twists, finding inspiration in individual struggles with emerging public policy on family planning, health care, homosexuality, immigration, substance abuse, literacy, domestic abuse, finance and more. In 1967, Mexican director Miguel Sabido deliberately set out to craft telenovelas with social messages on literacy, women’s rights, and cultural pride. In 1987, the US soap opera “All My Children” introduced a female character with AIDS and a plotline explaining how the disease could be prevented. Inter-American Development Bank research linked telenovela plots in Brazil with selection of infant names, increased divorce rates and decreased birth rates.

The curiosity can cross borders with “soap-opera diplomacy,” notes Geoffrey Cain, reporting for Time magazine how North Koreans risk death for South Korean soap operas.

During the past two decades, some governments and NGOs make no secret of using the genre to carry social messages, following the lead of early sponsors who urged clean homes: CARE developed “Wind Blows Through Dark and Light” for Vietnam to show that HIV/AIDS could strike any family; UK’s Plan International launched "Atmajaa" in 2008 to discourage female infanticide in India; US-based Search for Common Ground develops radio and television soap operas to teach conflict resolution for eight countries, including Angola and Nepal.

Of course, deliberate efforts to craft messages can be bumbling or self-serving. Earlier this year, Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez called on producers in his nation to focus less capitalism and develop “socialist soap operas.” And just before the prime-time mortgage crisis, Freddie Mac, which buys mortgages from lenders and packages them into bonds sold around the globe, and a North Carolina nonprofit teamed up to target US Hispanics with a 13-session telenovela warning against credit-card debt and offering advice for buying homes. By some reports, the show was viewed by more than 25 million before August 2007.

Douglas Schuler, writing for the Public Sphere Project, identified a secret behind the most popular shows: “Ideally the social messages in the soap operas and telenovelas are presented in the form of choices that can be consciously made – not injunctions or instructions which must be obeyed.”

In the end, good stories, language, fashion advice and technology boost a show’s exportability more than deliberate political messages or education. Aging audiences for US soap operas delayed an official online presence, whereas early regional exchanges gave Latin American firms a head start in repackaging shows, translations, video streaming and organizing fan bases cross borders. Networks continue to experiment with the genre and expand audiences. In 2005, the BBC introduced the animated soap opera, “The Flatmates,” for teaching English to immigrants, while also offering guides for using television to learn Spanish and other languages.

US networks likewise experiment with the telenovela formula, embracing a weekly rather than daily format. Shows like “Parenthood” in the US or “The Eastenders” in the UK target both genders. Even US crime shows like “CSI,” among the most watched in the world, rely on romantic tension and other features of the serial narrative.

But the US no longer monopolizes global television. Researchers from numerous disciplines analyze soap operas and telenovelas, agreeing that these modern folktales shape opinions, prompting viewers to reflect on their lives and prepare for social change. Researchers can’t predict which shows or formulas will inspire mass audiences, particularly cross borders, yet the competition may improve storytelling along with understanding of public policy in a complicated world.

Susan Froetschel, former assistant editor of YaleGlobal Online, is the author of three mystery novels, including Royal Escape.