A New Challenge for Bangladesh

A New Challenge for Bangladesh

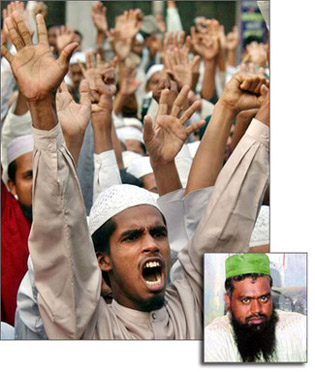

BLOOMINGTON: A specter of violent Islamic extremism haunts the state of Bangladesh. With global attention focused on Afghanistan and Pakistan, the rise of violent Islamic fervor in another part of South Asia has gone unnoticed. The desperately poor country with large ungoverned tracts could become a haven for Islamic terrorists, forced to vacate other countries. Consequently, the unchecked rise of the kind of religious extremism now happening in Bangladesh bodes ill for the country, its neighbors and indeed the world.

The rise of religious zealotry in Bangladesh poses a paradox. The country broke from Pakistan in 1971 despite the common bond of Islam. Its constitution declared that the country would be both democratic and secular. More to the point, despite periodic tensions between Muslims and Hindus, Islamic extremism was a marginal phenomenon, not cutting a wide swath across the country's political and social life. Some formal trappings of democracy still remain in place in Bangladesh. For example, the country still holds competitive elections, though marred by electoral violence. The secular dimensions of the state, however, have long been in decline, with formal commitment to secularism erased in the 1980s, during an extended span of military rule when Islam was declared the state religion of Bangladesh.

Residual commitment to the rights of religious minorities has all but evaporated. Bangladesh's dwindling Hindu minority population has borne the brunt of the wrath of the Islamic zealots. These developments have taken place under the aegis of a coalition that includes the Bangladesh National Party (BNP) and two religious parties, the Jamaat-i-Islami and the Islamic Oikye Jote (IOJ). Thanks to its parliamentary dependence on the religious parties, the BNP had evinced scant interest in containing the recrudescence of religious extremism. As a consequence, in the past few years, violent attacks on the opposition political party, the Awami League (AL), become routine; death threats against independent-minded journalists common; and the harassment of religious and sectarian minorities, primarily the miniscule Ahmadiyya community, widespread. Islamic zealots insist that men grow beards and wear skull caps while women don veils.

Politicians, deemed of a secular persuasion by zealots, have been assassinated. In the past few years, unknown assailants killed two prominent opposition leaders, Ahsanullah Master in May 2004 and SAMS Kibria in January 2005. In August 2004, the veteran Awami League politician, Ivy Rehman, was assassinated in a bomb blast at a political rally, which also almost cost the life of Sheikh Hasina Wajed, the leader of the opposition. However, the bomb killed 21 individuals at the rally and injured many more. Many suspect these attacks to be the work of a range of Islamist organizations, including the Jagrata Muslim Janata Bangladesh, the Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami and the Harakat ul-Jihad-i-Islami Bangladesh. Faced with systematic Western donor pressure, in March 2006, the government arrested one of the top leaders of the banned terrorist outfit Jama'atul Mujahideen Bangladesh, Siddiqul Islam, known as Bangla Bhai, literally “Bengali brother.” He is widely believed to have been involved in the brutal murder of several members of the Purba Banglar Communist Party.

What explains Bangladesh's precipitous lurch toward Islamic extremism? Several factors, some deep-seated, others of a more recent origin, are at work. Despite the country's rocky transition to democracy in the late 1980s, the norms of democratic political participation simply failed to take hold in Bangladesh. The two principal political parties, the BNP and the Awami League, differed little in their programmatic commitments, barring the BNP's known intransigence toward minorities. Commitments were woven largely around the personalities of their respective leaders, Begum Khaleda Zia, the wife of the assassinated military dictator, General Zia-ur-Rehman, and Sheikh Hasina Wajed, the daughter of the slain founder of Bangladesh, Sheikh Mujibur Rehman. The necessity to please donor communities forced both political parties to participate in minimally competitive elections. However, neither party demonstrated much willingness to abide by the election results. Consequently, parliamentary proceedings frequently became farcical, with the defeated party either boycotting the proceedings or resorting to rallies, strikes and demonstrations to scuttle the other's policies.

Both parties played a role in undermining political institutions. For example, intent on imposing their will, they routinely removed senior civil servants after each national election, replacing them with individuals known for partisan loyalties. Thus, both the neutrality and probity of the civil service has long been compromised. Similarly, police and paramilitary forces have become the handmaidens of the party in power.

The institutional decay allowed for the rise of religious intolerance. As the BNP and AL regimes alike proved to be inept and corrupt, they needed facile explanations for their failures of governance. The AL largely blamed the BNP and offered some semblance of protection to minorities to garner their vote. The BNP, on the other hand, not content to simply attack the AL, resorted to populist scape-goating. Minorities, especially Hindus, were characterized as being agents of the neighboring behemoth, India. With a rising tide of Islamic fervor, the last elements of a syncretic Bengali culture are under attack. Since 2001, the government formally banned Poila Baisakh celebrations that herald the traditional Bengali new year. The BNP could pursue such strategies with impunity because of the increasing anemia of political institutions and a free, but frequently irresponsible, press.

Yet domestic factors alone cannot explain the turn toward radical Islam. External forces are also at work. Periodic harassment and violence toward Muslims in India, like killing of Muslims in Gujrat, became fodder for the Islamic zealots in Bangladesh. The regime and its ardent supporters boosted the cause of Islamic solidarity through the exploitation of unfortunate events in India.

Two other convergent forces have facilitated the promotion of religious confraternity. Though hard to measure, ample funds have flooded Bangladesh in recent years from Saudi religious charities, spawning the growth of Wahhabi madrassas across the country and propagating a particularly parochial and xenophobic vision of Islam. Weak state institutions that might regulate their growth, combined with the lure of monetary rewards for clergy and acolytes, have enabled the madrassas to thrive.

A final factor explains the growth of religious zealotry. In an effort to sow discord in India's troubled northeastern states, Pakistan’s Inter-Services Intelligence Directorate (ISI-D) has also penetrated Bangladeshi society. Despite the horrors that the Pakistani Army had perpetrated in East Pakistan in 1971, which contributed to the emergence of Bangladesh, a small segment of Bangladeshi society maintained its fondness for a unified Pakistan. In large part, loyalty to Pakistan stemmed from an unyielding hatred for India.

The convergence of domestic and external forces threatens to envelop Bangladesh. Owing to real and imagined grievances of Muslim populations in the Middle East and elsewhere, the world has witnessed a growing strand of violent Islamic zealotry that threatens the stability of states from Indonesia to Pakistan and even parts of Nordic Europe. Unless the external world, well beyond the reaches of South Asia, takes heed and contains the spread of Islamic extremism in Bangladesh, it may eventually confront a more powerful and hydra-headed monster. The zealots that the madrassas spawn will not be content to wreak havoc in Bangladesh and instead will become the next foot soldiers of the global jihad.

Sumit Ganguly is a professor of political science and holds the Rabindranath Tagore Chair at Indiana University in Bloomington.