New Energy Frontiers Expand Global Connections – Part I

New Energy Frontiers Expand Global Connections – Part I

WASHINGTON: One cannot open a newspaper without reading the word globalization, yet vast areas of the world are left out of a globalized network for a simple reason: lack of electricity. Denied power, rural communities continue to remain isolated, mired in poverty, deprived of the potential for economic development and modern social services.

The quest for electricity by rural communities comes at a time as energy prices climb, fossil fuels are in decline and emerging carbon markets promise income from climate-neutral forms of energy generation. As a result, rural locations could be the pioneers for some alternative forms of energy.

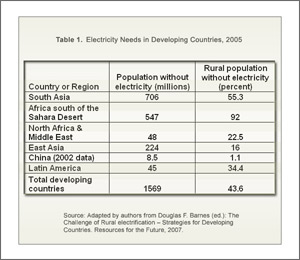

More than 40 percent of the rural population in developing nations lack access to electricity, and the problem is especially stark in Africa, with more than 90 percent of its rural population lacking access. (See Table 1) That means laborers are limited to toiling daylight hours, students cannot read into the night and any family activities take place by fire or flashlight.

Lack of electricity also means that inhabitants of rural areas in developing countries cannot share in many benefits of globalization – including the internet and telecommunications, which increase the flow of information, allowing producers to market their wares, shoppers to compare prices or quality, and ordinary people to discover new ideas and opportunities.

Yet, in a number of countries electricity availability has enabled so-called Infoshops to establish a technology-based information resource on matters of relevance for rural dwellers, from cost and availability of farming inputs such as seeds and fertilizers to directories of local veterinarians and animal-husbandry programs. For instance, the Pallitathya, a “Rural Information” program in Bangladesh, provides communities with internet-based information on agriculture, health, education, law and human rights, appropriate technologies, disaster management and government services. “Infomediaries,” or interpreters of digital content, and mobile-phone helplines use the comparably high mobile-phone penetration in rural Bangladesh, pioneered by Grameen Phone, and make information accessible even for the illiterate.

While there’s no dispute over the value of bringing electricity to the villages, experts are divided over how to deliver it. Should the national power grid be expanded to the rural areas or should one opt for decentralized power generation? Grid expansion is the most economical option in areas close to the country’s main electricity grid and in densely populated areas; it’s also the most tried form of power delivery, undertaken in almost all countries. Decentralized generation capacity, on the other hand, has proven more economical in remote, dispersed communities, where grid expansion would lead to high cost of access per person connected.

Ambitious rural electrification programs have been carried out in Brazil and China. More recently, initiatives in Uganda, Tanzania, Rwanda, Kenya and Ghana are well underway. In Brazil alone, the $8 billion Luz Para Todos, or Light for All program, has reached more than 8 million new beneficiaries using grid extension, localized minigrids or off-grid electrification, with a goal of reaching 10 million users. The focus has been on poorer states with low levels of connectivity, notably in the country’s north.

Aside from distributing power, the method of generating electricity has become a debated issue. Off-grid access has traditionally been diesel-driven. Recently, however, that’s changed because of increasing concerns about harmful emissions at the local and even global levels, resulting in high costs over the long-term. As a result, renewable sources – solar, wind and small-scale hydro – are increasingly popular for small-scale off-grid electrification. Small hydroelectric projects are widely used in China, wind power in numerous Mexican efforts and solar in Morocco.

Reaping the gains of globalization via electricity access requires additional investments in “productive uses” of electricity, defined as activities that put electricity to work for people’s welfare – either through income generation or by facilitating the provision of health and education services.

Productive-use programs can help communities reap the gains of electricity access in three main ways:

● Enabling development: When communities receive electricity, this does not immediately or directly translate into development. It depends on how power is used. The processing of agricultural goods or crafts for sale, using power to offer educational material or simply providing illumination for evening school are examples of developmental use of power. Of course, availability of power is essential to encourage more community participation through the use of e-government applications.

● Promoting appreciation for and local ownership of electricity services and technology: Once individuals understand that electricity services lead to community improvements – providing a source of income, making routines easier – then it’s likely that individuals will work to protect electricity equipment from damage or theft. A sense of ownership of the technology is an essential component for maximizing a system’s lifetime.

● Giving communities a means to pay for energy services: Productive-use activities may allow communities to generate income from their activities so that they can pay for electricity services – thus moving rural electricity access towards cost recovery. For communities of limited financial means, targeted and monitored subsidies may also be required so that service is provided regardless of the community’s ability to pay.

Experience to date has resulted in a number of lessons for project planners when designing electricity systems with productive uses in mind. Electrification schemes and productive-use efforts are more likely to succeed if communities have an adequate understanding rather than act as passive recipients. Project managers need to understand that successful introduction of productive-use programs is likely to improve sustainability of electrification programs. Likewise, it’s crucial that any programs be accompanied by community training on operation and maintenance as well as follow-up with providers.

When selecting productive-uses program, the decision process should review funds available and community capacities, and thus prioritize activities. This involves calculating the gains from various productive uses. Ultimately, of course, communities themselves should choose the most effective option to improve their quality of life.

Local institutions are normally knowledgeable about the resources and needs of the nearby communities. Similarly, local NGOs generally have a solid network in the target community and can thus aid in dispelling doubt. Both foreign donors and relevant domestic government agencies must coordinate their efforts to tie in productive uses with community needs and abilities, and with existing efforts in agriculture, health or education.

Usually, the choice of technology for rural electrification – grid connection versus diesel, micro-hydro, wind or solar – is based on least-cost considerations. This may change when productive uses emerge. For instance, if an essential service for one community is investment in critical electricity-fed health equipment, then reliability rather than average cost of supply becomes a critical factor in choosing between technologies. Similarly, if a priority is small-scale tourism, then meeting peak demand during holiday seasons becomes crucial.

Private investment remains an option to enable some forms of productive uses. However, the benefit of private capital must be weighed on a case-by-case basis against the potential pitfalls, including monopolies and higher long-run costs.

Examples of successful rural electrification with productive-uses applications are encouraging. For instance, the Mexican mountain village of La Vainilla has used solar panel-based electrification to give its inhabitants light for work and study, combining access with investment in a small water-purification system that generates income through sales to a nearby hotel.

If carried out sensibly, then electrification of poor, rural communities will ultimately mean more equitable distribution of the gains from globalization – and indeed enable inhabitants to participate in globalization through more effective marketing of products. The communities can also shape globalization by making their voices heard via modern communications applications in national or international decision-making processes.

Adriana Valencia and Georg Caspary have worked on the planning and implementation of rural electrification projects in numerous countries.