North Korean Purges Threaten Relations with China

North Korean Purges Threaten Relations with China

SEOUL: In a country where purges are as commonplace as polling in democratic countries, the summary execution of North Korea’s number two figure Jang Song Thaek, 67, was breathtaking in its brutality. Extensive tentacles of his power and influence, as well as his reported close relations with China, the most powerful neighbor, makes this purge akin to a political earthquake with shockwave likely to be felt inside and outside North Korea for months to come.

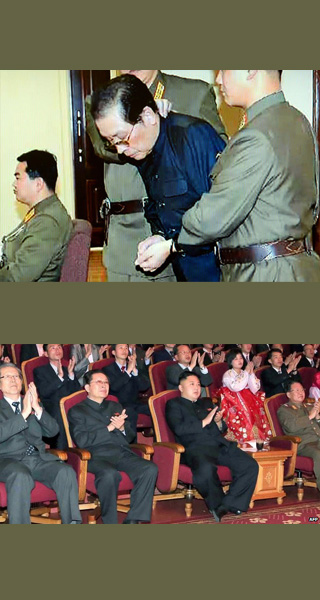

News that Jang, uncle and regent to North Korea’s young dictator, had been executed on 12 December stunned the world with unprecedented video footage showing the victim physically removed from a meeting and later dragged into a military trial with tied hands. Among the litany of charges was the accusation of betraying North Korea to an unnamed country, assumed to be China.

Jang, who married Kim Kyong Hui, the only daughter of North Korean founder Kim Il Sung, rose to be a party secretary and vice chairman of the all-powerful National Defense Commission. Kyong Hui, a thin aging woman reportedly suffering from alcoholism and for many years living in separation from Jang.

Although the Moscow-educated Jang was said to have a fondness for drinking parties and pretty women, he rose rapidly on the wings of kinship with the Great Leader’s family. But his penchant for collecting cronies bred suspicions of faction-forming and led to a two-year banishment from central Pyongyang in 2004. He bounced back to take charge of the Central Administrative Department of the Workers Party, responsible for supervising legal and security branches of the regime.

Even as his marriage foundered on rumors of philandering, Jang was asked to take over the role of regent following the death of iron-handed Kin Jong Il in December 2011 and mentor the son. In a show of his closeness to the Kim family, Jang accompanied the Supreme Commander on more than a hundred inspection trips across the country last year. When the number of joint trips plunged by a half this year, the South Korean National Intelligence Service, or NIS, began suspecting difficulties. The spy agency’s suspicion thickened into alarm upon discovering that Jang’s two closest deputies at the Administrative Department – Ri Yong Ha and Jang Su Gil – had been executed by firing squads. It also discovered that the North Korean ambassadors in Malaysia and Cuba, both close relatives of Jang, had been mysteriously recalled home. Then NIS broke the story of Jang’s purge to the South Korean parliament on 3 December, almost a week ahead of confirmation by the North’s politburo.

NIS director Nam Jae Jun revealed that mysteriously missing from public view was another Jang protégé, Pyongyang’s former ambassador to Geneva, a financial expert whose main duty was looking after the Kim family’s overseas bank accounts. He also reported to parliament that the number of firing-squad executions, mostly by submachine-guns, has risen from 17 cases in 2012 to 40 in 2013.

In Seoul, analysts say Kim Jong Un, whether independently or backed by army hardliners, is out to clean his stable of suspicious advisors, most of them pragmatists involved in repairing the country’s dire economic condition under the UN-imposed sanctions. Jang was regarded as head of this economy-first group busily seeking to bring more Chinese investments to the large joint industrial zone being developed on an island on the Yalu River and especially for upgrading Rajin-Sonbong port facilities, leased to China for a 50-year period.

Analysts speculate that frenetic activities of hundreds of Jang’s cadres working in the foreign-trade sector – many active in Beijing, Shenyang, Hong Kong, Guangzhou and Southeast Asia – might have produced morbid suspicions for young Kim. Not only was Jang building a significant independent power base in a nation demanding absolute loyalty to one man, he might also have alienated powerful players, by reportedly taking over some substantial foreign-exchange earning projects previously in military hands. If true, this meant fewer resources going to the army in a regime that openly flouts a so-called army-first policy. The possibility of jealous army generals whispering into Kim’s ears for Jang’s ouster cannot excluded.

The Ministry of State Security’s special military tribunal accused Jang not only of using current economic hardships to stage a coup, but also for supporting the disastrous 2009 currency reform that nearly destroyed the economy with hyperinflation. The reform and the special industrial zone he sponsored came from policy decisions at the top, with Kim Jong Il taking credit. Pak Nam Ki, then chief financial director of the party, was swiftly executed by firing squad in 2009. Blame eventually spread to Jang, too, and the tribunal accused him of “selling cheaply,” to an unnamed foreign country, resources like coal, timber and minerals as well as the lengthy lease for the Rajin-Sonbong port. Jang was also accused of stealing €5.6 million from the state bank for gambling.

Jang’s other crime was factionalism or sectarianism, the act of building private independent networks of cadres loyal to his cause of economic recovery. These cadres are the so-called “foreign exchange earners” scattered through China and Southeast Asia, including North Korean restaurants. NIS sources say dozens of North Koreans in Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzen have disappeared in the last few days, apparently going into hiding. So are hundreds of Juche, or self-reliant, businessmen in China and Southeast Asia said to be in panic and hiding, looking for a chance to defect to Seoul or even to the United States, NIS officials say. South Korea should expect more refugee arrivals in the months ahead.

Prospects of continuing purges loom, wiping out any lingering hopes that the Kim regime will follow the Chinese model and embark on economic reform. “The purges have certainly lowered the possibility of the North taking the way of reform,” said Suh Sang Kee, the ruling party legislator chairing the parliamentary intelligence committee, flatly adding, “In fact, the purge confirms that the North has no future at all.” Even so, Seoul has agreed to meet the North for talks at Kaesong Industrial Zone next week. The North’s proposal clearly intends assurances that nothing untoward is underway, and rejection by Seoul runs the risks of aggravating the peninsula’s security.

More puzzling though is China’s long-term ties with a rogue regime armed with nuclear weapons and missiles. North Korea quickly snuffed out the life of a contact with whom China has comfortably conducted business for many years, despite the fact that Beijing provides half of the North’s food and 90 percent of its fuel needs. In a muted reaction, China’s Foreign Ministry spokesman Hong Lei blandly described the Cultural Revolution–style executions in the neighboring state as “internal affairs” and expressing hope for “stability.”

Deep down China has many reasons to worry about this lurch to anti-market, anti-Chinese extremism by a country that has already flouted China’s advice warning against nuclear tests. While the world expects China to restrain its reckless ally, Beijing can’t help but ponder how to contain the fallout from a rupture in economic ties with North Korea and not let widespread purges threaten stability on its eastern border. Execution of Jang and associates may force China to rethink relations with Pyongyang.

Shim Jae Hoon is a Seoul-based journalist.