North Korea’s Missile Trade Helps Fund Its Nuclear Program

North Korea's Missile Trade Helps Fund Its Nuclear Program

SEOUL: It is still uncertain whether North Korea, as it claims, really possesses, or is capable of producing, nuclear weapons, or if the enigmatic regime in Pyongyang is merely using the issue as a bargaining chip to extract concessions - and aid -from the United States and other countries in the West. But there is no doubt about its missile program. North Korea earns substantial revenue from the sale of missiles, and missile components and technology. This certitude regarding the financial source for its nuclear program makes an all out attempt to stop North Korean missile export even more urgent. Sources in Washington say that the Bush Administration is heading in that direction.

"They [the North Koreans] are the No. 1 proliferators of missiles, and also of conventional weapons," Gen. Thomas A. Schwartz, former commander of the United Nations and the US forces in South Korea, told the US Senate Armed Services Committee last year. "That is how they have kept their economy alive, and they are actively pursuing those interests around the world."

If proof was needed, the interception in December 2002 of a Cambodian-registered, North-Korean owned ship carrying ballistic missiles, proved it. Working on a US tip, Spanish marines patrolling the sea boarded the ship and found 15 scud missiles, 15 conventional warheads, 23 tanks of nitric acid rocket propellant and 85 drums of unidentified chemicals under a cargo of cement bags. The destination of the shipment was Yemen. Yemen is believed to be a relatively new buyer of North Korean missiles. It is not entirely clear why Yemen decided to purchase such advanced weaponry. According to US sources, other customers of North Korean missile parts and technology include Pakistan, Iran, Egypt, Libya, Syria and Vietnam. The missile sales to "rogue states" in the Middle East and Asia have raised fears that at least some of these missiles might end up in the hands of international terrorist groups.

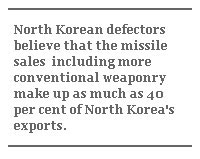

US military officials in South Korea assert that missile sales play a vital role in propping up the Pyongyang regime. In 2001 alone, North Korean exports totaled $560 million, a substantial figure for a country with an estimated annual GDP of approximately $17 billion. North Korean defectors believe that such sales - including the sale of more conventional weaponry-make up as much as 40 per cent of North Korea's total exports.

Despite having caught the North Koreans red-handed shipping ballistic missiles, the US allowed the ship to continue to its destination, Yemen -- then a valuable partner in America's war against terrorism. A similar concern about not upsetting a major ally in the Middle East that receives sizable American aid might explain the US reticence about another clandestine missile deal between North Korea and Egypt.

The case of the North Korean sale of missile and related technology to Egypt, that was recently discovered, offers insights into how these sales are conducted. In August 2002, a North Korean couple based in Bratislava in Slovakia, was found buying dual-purpose goods in China, Russia and Belarus and then exporting them to the Kader Factory for Developed Industries, an Egyptian government-funded military complex in Cairo. The couple, Kim Kum Jin and Ri Sun Hui, was found driving a black Mercedes and living in a luxury apartment in Bratislava, where they counted among their neighbors, the city's mayor and a cabinet minister. According to Slovak investigations, both turned out be high-ranking North Korean agents with ties to Bureau 39, a shadowy wing of the ruling Korean Workers' party controlled by North Korean leader Kim Jong Il. Western and Asian intelligence agencies believe Bureau 39 was set up in 1994 to generate hard currency for Kim's impoverished nation. Although Kim and Ri fled Slovakia before the authorities there could deliver an expulsion order, they left behind invoices and account books, which indicated that they were dealing in tens of millions of dollars worth of chemicals, military vehicles, and missile components.

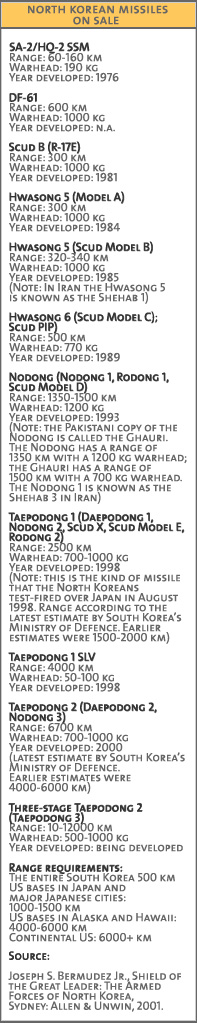

It is now clear that the "Egyptian connection" played an important role in North Korea's missile development which grew along with its sales. Pyongyang produced its first missile in 1976, a SA-2/HQ-2 SSM with a range of only 60-160 km. But its more advanced missile program began in the early 1980s when the Egyptians supplied North Korea with Soviet-made Frog artillery rockets and Scud B missiles - liquid-fuelled, surface-to-surface missiles that can deliver 1,000-kilogram payload up to 300 kilometers away.

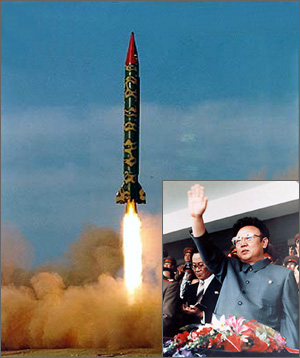

Analysts believe Egyptian generosity was in return for Pyongyang's assistance during the October 1973 war between Egypt and Israel. It gave the North Koreans a new lifeline. The North Koreans reverse-engineered the Scuds and soon began to manufacture them as Hwasong 5. A longer-range version, called Hwasong 6, was produced in 1985. It was followed in the 1990s by Medium-range and Intermediate-range ballistic missiles (see box). The revenue earned from its export seems to have been ploughed back to develop a new line of missiles. On 31 August 1998, North Korea test-launched a two-stage ballistic missile, Taepodong I. In 2000, North Korea developed its most advanced Intercontinental ballistic missile, the Taepodong 2. Taepodong 2 has a range of 6,700 kilometers-enough to reach the North American West Coast.

But it is North Korea's missile sales to other countries, rather than the possibility of nuclear attacks on US targets in the Pacific, that has security analysts worried. As early as 1989, North Korea sold Scud-B and C missiles to Iran. In 1993, Teheran received the delivery of the first North Korean medium-range ballistic missile, the Nodong 1. In Iran, this missile became known as the Shehab 3. With a range of 1350-1500 km, it can theoretically hit Israel with a payload of 1,200 kilograms of explosives. A few years later, Libya acquired missile components from North Korea, although there is no evidence that it possesses complete Nodongs.

Pakistan is another important customer for North Korean missiles and missile technology. In 1999, the US National Intelligence Estimate publicly confirmed what had long been suspected within the international intelligence community: Pakistan had both Chinese-made M-11 short-range ballistic missiles and North Korean-supplied medium-range missiles. The latter was termed "Ghauri" in Pakistan, but was based on technology used in North Korea's Nodong missile. The present nature or extent of military co-operation between North Korea and Pakistan - now an important US ally in the war against terrorism - is unclear. However, in early April the US imposed sanctions on a North Korean company, Changgwang Sinyong Corp., for selling missiles to Pakistan.

During negotiations in Beijing in April this year, North Korean negotiators told their US counterparts that they had completed reprocessing 8,000 spent nuclear fuel rods that could provide enough plutonium for six bombs. If true, North Korea clearly has the delivery systems to pose a significant threat not only to neighboring countries such as South Korea and Japan but also the United States.

Many would argue that Pyongyang's willingness to sell missiles to any country that is able to pay for them makes North Korea a bigger threat to world peace than Saddam Hussein's Iraq ever was. North Korea's global reach and its penchant for using weapons of mass destruction as a bargaining tool, also suggest that it will be a more formidable opponent than Iraq to the United States. During the April 2003 talks in Beijing, North Korea reportedly offered a plan that, according to US Secretary of State, Colin Powell, "would ultimately deal with their nuclear capability and their missile activities but they, of course, expect something considerable in return." The Bush Administration is in no mood to offer North Korea anything. While the US may meet North Korea at another time for talks, Washington is now focusing on finding ways to choke off North Korea's lethal exports.

Bertil Lintner is Senior Writer for the Far Eastern Economic Review and the author of six books. The most recent is “Blood Brothers: Crime, Business and Politics in Asia.”