Nuclear Pact Launches India Into Uncharted Waters

Nuclear Pact Launches India Into Uncharted Waters

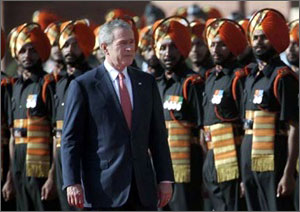

NEW DELHI: The recently signed Indo-US nuclear deal welcoming India to the world of recognized nuclear power has been termed historic, and for once that may not be usual media hyperbole. Though only the future will determine its true significance, there is little doubt that the nuclear pact is an emphatic acknowledgment of India’s transformation from a regional to a global power, an important step in transforming the rules of the world order to accommodate the aspirations of a rising power. Beyond these obvious implications, the measure of the tectonic shift that the Indo-US entente implies will be revealed in its impact on both the world’s non-proliferation regime as well as India’s strategic posture, its economic-development and foreign-policy orientation. As the fallout from the nuclear deal becomes clear, India may be seen to have made an immediate strategic gain while underestimating the long-term political consequences.

The deal was supposed to be a balancing act between India’s desire to maintain maximum autonomy over its military nuclear program and the rest of the world’s desire to cap that program. While all the details are not available, at this juncture it appears that the deal gives a distinct advantage to India at the expense of the global non-proliferation goal. While India has agreed to safeguards for its civilian reactors in perpetuity, it has artfully tied them to assurances on an uninterrupted fuel supply. India has retained the right to designate future nuclear plants as civilian or military, it can divert indigenous fuel entirely for military use, and the number of plants kept outside the purview of inspection seems large enough to allow a credible military program. It will be difficult to argue that this deal significantly caps India’s nuclear capability. If the deal goes through, India will have managed to transform the rules of the international order without sacrificing its military autonomy.

Will accommodating India weaken the non-proliferation regime, as many critics have claimed? As a practical matter, it could be argued that states like Iran and North Korea will do whatever they wish, regardless of the choices made with respect to India. The choices of countries to go nuclear will be determined more by their perception of security threats and the compulsions of their domestic politics than choices made by third countries. India’s treatment as an exception is not arbitrary but principled. India satisfies the criteria of what is called a “responsible” nuclear power: a democratic country that does not engage in proliferation. Iran, Pakistan, North Korea or, for that matter, China do not meet this criteria. But while a principled case can be made for accepting India, this deal further legitimizes the possession of nuclear weapons. If legitimizing nuclear weapons as such poses a risk to the world order, this deal enhances those risks.

On the economic front the interdependence of India’s economy with that of the US is only bound to increase. India now becomes an attractive market for nuclear and advanced technologies worth billions of dollars. Both sides justify the deal in economic terms. India’s ruling classes are convinced that nuclear power is necessary for its energy security. It is the only viable answer to India’s acute power shortages. The US also wants to re-legitimize the worldwide use of nuclear power as the only alternative to burning hydrocarbons. But will dependence on nuclear power really give India the energy security its needs? Although the terms of the deal safeguard the import of uranium, will it be wise for India to base its energy security on imported supplies of uranium? And are the economic arguments in favor of nuclear power over alternative sources so compelling that it becomes the cornerstone of India’s development strategy?

While the desirability of India’s energy strategy can be debated in technical terms, the political consequences of this deal are far more uncertain than India acknowledges. The nuclear deal is simply one aspect of an Indo-US relationship that is acquiring unprecedented momentum. For the first time in its history, the fortunes of India’s elites are comprehensively and intimately tied with the fate of America. Can India be so materially and culturally bound with the US and yet resist seeing world geo-politics through American eyes? While formally India acknowledges that it will not always align with the US, there are signs that India is subtly internalizing the terms of discourse through which the US describes the world order. Take for instance, the war on terrorism. India and the US have emphatically reiterated their common interest in defeating terrorism. But it is still not clear that it makes sense for India to buy into the idea that there is a single kind of terrorism or a united war against it. India was a victim of terrorism that had its roots in the geo-politics of South Asia, not in the militant Islam that targets the West. Both are different entities that require different responses. India’s strategy of military self-restraint in the face of terrorism has also been politically prudent, while US military actions have, arguably, given terrorism more aid and succor. Is India now in the danger of being drawn into the confrontation between militant Islam and the West, a confrontation that is not of its making?

Of the foreign policy dilemmas that the deal will produce, the most important one revolves around China.. The US projects India as some sort of counterweight to Chinese power. It is odd not to help build India while the Chinese juggernaut roles on unabated. While not acknowledging it overtly, India is also preoccupied with containing Chinese influence. What effect will the deal have on India’s relations with China? The answer to this question depends on how US-China relations evolve in the future. If relations between the US and China worsen, India, by aligning with the US, risks becoming a frontline state in that confrontation. But while the prospects of such a scenario should not be exaggerated, there is more immediate cause for worry. While the US has emphatically rejected equating India and Pakistan in any nuclear order, will China do the same? Some argue that China will assist Pakistan, regardless of what India does. So does an increasing alignment with the US raise China’s stakes in the subcontinent? Will it be licensed to scale up its nuclear cooperation with Pakistan? China has also offered Bangladesh civilian nuclear cooperation. The prospect of Pakistan and Bangladesh possessing significant numbers of civilian nuclear reactors is not one that the world, at this juncture, should contemplate with equanimity. As the Iran crisis has demonstrated, the line between civilian and military nuclear use is, to put it mildly, a contentious one. In the chess board of great power politics, the moves of every nation, knight or rook, are equally important.

Coming months and years will show that the Indo-US deal is not just a bilateral pact; it will have consequences for the behavior of other nations. And prudence requires that India acknowledge the unpredictability of those consequences and brace itself.

Pratap Bhanu Mehta is president of the Center for Policy Research in New Delhi, India.