Obama and the World: Time to Deliver

Obama and the World: Time to Deliver

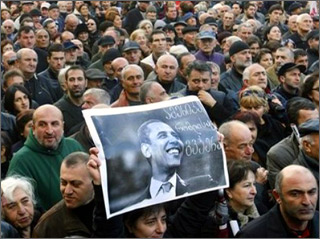

WASHINGTON: Barack Obama’s inauguration as the 44th president of the United States was watched by a record number of people outside the country, hopeful that he would guide the world towards peace and stability. Euphoria created by the Obama feel-good-factor will soon be sorely tested as the new administration confronts the thorny Bush legacy in Gaza, Iran, Afghanistan and North Korea. Obama must transform US foreign policy from spurts of interventionist moves and short-term fixes to a well-thought out global approach that encourages long-term cooperation with others on many pressing issues.

The gushing headlines and random man-in-the-street interviews are deceptive, transitory snapshots of emotional moments. Temporarily disregarded amid post-inauguration Obamamania are widespread pre-election doubts around the world about the new American president’s ability to effect meaningful change in US foreign policy.

Before the election, only a small minority of Egyptians, Jordanians and Lebanese thought the next White House resident could make a difference in US foreign policy, according to the Pew Global Attitudes Survey. That is hardly fertile ground for an Obama-led Israeli-Palestinian peace initiative.

Obama faces a similar credibility challenge in dealing with Afghanistan and Pakistan. Last year only one in five Pakistanis thought replacing George Bush would prove a change for the better in US foreign policy. And in 21 of 23 countries Pew surveyed, a majority or plurality of those questioned wanted US and NATO troops out of Afghanistan as soon as possible.

Obama’s diplomatic test is no less daunting in Northeast Asia. The new administration’s top regional foreign policy priority is likely to be restarting nuclear talks with North Korea. But the Japanese people are more concerned about the return of their citizens allegedly abducted by Pyongyang than they are about North Korea having nuclear weapons, according to the Japanese cabinet office’s recent annual survey of Japanese public opinion on foreign affairs. And a majority of Chinese, Japanese and South Koreans told Pew they doubt that a new US president will make much difference to American foreign policy.

The advent of a new administration in Washington provides a window of opportunity for the United States to overcome these doubts and to re-inspire faith in American leadership in the Middle East and in Southwest and Northeast Asia. To demonstrate to skeptics around the world that his election signals more than a feel-good moment, Obama needs to make a series of significant gestures in his first months in office.

The Middle East: Reestablish Washington’s image as an honest broker in the decades-old Arab-Israeli confrontation by being tough with Israel on almost any topic. The substance is less important than the effect of being seen on the Arab street as defying the Israeli lobby in Washington and taking the Arab side occasionally. Cairo, Amman and Damascus need this shift in public sentiment to give them domestic political space to compromise with Israel in future negotiations. Obama’s appointment of former Senator George Mitchell as his special envoy to Middle East is a first step. Mitchell has a reputation for fairness and balance.

Challenge regional Arab actors to put up or shut up by offering US support for the Syrian-Israeli negotiations suggested by Turkey, the Hamas-Fatah talks that Egypt has been trying to broker and the Arab-Israeli initiative proposed by Saudi Arabia.

Convince the Europeans, and possibly the Japanese and the Indians, to police the Gaza-Egyptian border and the Gaza coastline to interdict weapons shipments. An embargo will diminish Hamas’ ability to attack Israel and deny Israel an excuse for reoccupying Gaza.

Open negotiations with Tehran. The generation-long US cutoff of diplomatic relations and economic embargo have failed. Washington stands alone. Europe, China, India and Japan need Iranian energy and will not support a policy of continued isolation. Pursue US engagement through tourism, student exchanges, trade and investment. Accept that Tehran is going to have nuclear weapons and develop non-proliferation controls. Support a regional dialogue between Iran and its neighbors. But don’t be a pushover. Demand quid pro quos from Tehran.

Southwest Asia: Reverse Obama’s bellicose campaign rhetoric about Afghanistan and signal Washington’s intention to eventually disengage. Afghanistan is a quagmire. Ask the British or the Russians. Most of America’s allies want out. Washington cannot expect more European troops to back up the GIs in Afghanistan. So challenge the Europeans and the Japanese to put their money where their mouths are and boost their economic redevelopment assistance. Spend some of the billions Washington will save drawing down forces in Iraq to provide education, health care and job opportunities for Afghanis. Publically warn Afghan President Hamid Karzai that America’s withdrawal timetable depends on his crackdown on corruption. The more honestly and effectively he spends economic development assistance, the longer Americans will stay. And make it clear that Afghani sovereignty will not get in the way of the United States defending itself. Washington will strike back from the air and with special forces’ operations if terrorist training camps reemerge in Afghanistan. Richard Holbrooke, Obama’s new special envoy for Pakistan and Afghanistan, is a blunt-spoken realist who can deliver this message loud and clear.

Focus on Pakistan as the long-term threat to regional stability because of Islamabad’s inability to control its own territory, Pakistan’s nuclear arsenal and the ever-present danger of war between Pakistan and India. Offer a 90-day pause in US drone bombing of suspected terrorists living on Pakistani territory, which is alienating Pakistani public opinion, in return for meaningful Pakistani military action against terrorist operations. Challenge the Europeans, Japanese and Chinese to counter the fundamentalists’ appeal by building schools, clinics and factories to afford Pakistanis a better life. And restrain New Delhi. Whatever the provocation, war will only make conditions in Pakistan worse. Pressure Islamabad to turn over suspected terrorists to Indian authorities and launch back-channel efforts to reduce tensions in Kashmir.

Northwest Asia: Restart discussions with the North Koreans by sending an American team of non-governmental experts to Pyongyang to begin a dialogue on how to have more effective negotiations about the North Korean nuclear weapons program. Tell Tokyo that it is free to pursue its own diplomacy with Pyongyang about the abductees. But the nuclear talks with North Korea will eventually continue, with only five parties if Japan cannot participate for domestic political reasons. Challenge Beijing to ratchet up its pressure on Pyongyang as a sign of Chinese willingness to work constructively with the new US administration. And pass the US-Korea Free Trade Agreement as a signal of continued US engagement in the region.

There is a palpable, collective relief around the world that the Bush era is over. And the excitement that a young African-American has now become president of the United States is genuine. But Obama should not confuse the enthusiasm of the moment with support for American foreign policy in the long run. Rebuilding trust in the United States requires Washington to break with the past.

No one expects Obama to resolve longstanding problems overnight. But his first few months in office are a time to set the tone for his foreign policy by offering bold initiatives to address stalemated crises in hotspots around the world. He will never have this opportunity again.

Bruce Stokes is the international columnist for the National Journal.