Oil and Gas in Islam’s Faultline

Oil and Gas in Islam’s Faultline

BLOOMINGTON: Because access to oil and natural gas is a major driving factor for foreign policy, it is necessary to look strategically at groups controlling the future of supplies. Understanding the changing power balance between Sunnis and Shiites, or Shias, in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula region also offers insights into the growing unrest there over democratic rights. The religious schism between Shiites and Sunnis that emerged in the 7th century, now mixed with oil, gas, political power and military muscle, has acquired a new volatility that goes ignored at international peril.

Policymakers, the public and scholars recognize that Sunnis make up the majority of Muslims and that Shiites form a small minority. According to a Pew Research Center study in 2009, “Of the total Muslim population, 10–13 percent are Shia Muslims and 87–90 percent are Sunni Muslims.”

However, global generalization fails to focus on demographic distributions in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula. Nor does it take into account the geopolitical impact of Muslim sectarianism and the strategic implications of the Sunni-Shiite divide for access to natural resources from that energy rich region. As Saudi Arabia and its Sunni partners draw increasingly upon crude oil and natural gas resources to meet the demands of an energy-hungry world, Iran and its nearby Shiite partners hold on to similar resources not by choice but through sanctions and strife. So, in the long run, nations in the region with predominantly Shiite populations could determine who receives much-needed resources.

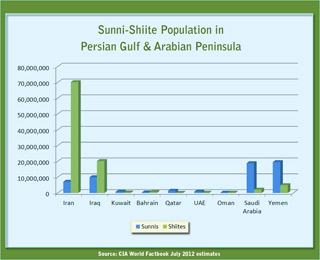

When official demographic distributions, from CIA World Factbook July 2012 estimates, for the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula are examined, it becomes evident Sunnis comprise 36 percent of the overall population whereas Shiites make up 60 percent. Other Muslim groups, Bahais, Christians, Jews, Zoroastrians and Hindus constitute the remaining 4 percent (see Figure 1).

Bahraini and Kuwaiti monarchies vest power in Sunni populations, augmenting their numbers by granting citizenship to Baloch and Pashtuns from Pakistan and Afghanistan while repressing the aspirations of their own Shiites. Official figures place Shiite citizenry at 65 percent of Bahrain’s population and 30 percent of Kuwait’s, although unofficial tallies by the Council on Foreign Relations and by Islamic Web suggest at least 75 percent of Bahrainis and 55 percent of Kuwaitis follow Shiism. Likewise Saudi Arabia, another Sunni monarchy, presents itself as overwhelmingly of the Wahhabi sect. Yet official Saudi demographics also under-represent that kingdom’s Shiite population, estimated by scholars at 25 percent. Qatar and the UAE too have larger numbers of Shiite citizens than officially reported.

One reason for those countries understating their Shiite populations is obvious: Retaining political power in Sunni hands. Another reason is increasingly relevant: Shiites tend to occupy oil and natural gas rich regions yet rarely share equally in the profits. A third reason has to do with global politics: The region’s Sunni leaders fear the West will pressure them into more power sharing and wealth distribution in order to ensure sociopolitical stability. Indeed scholarly tallies place the approximate total number of Sunnis at 54,702,317 and of Shiites at 102,357,949, or 33 percent and 62 percent respectively, of overall population in the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula region.

Proven crude oil and natural gas reserves, from CIA World Factbook January 2011 estimates, are equally revealing as to how each Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula nation’s Sunni and Shiite populations correlate with control of energy resources (see Figure 2).

Enlarge Image

Those countries which officially claim Sunni majorities, namely Saudi Arabia, Yemen, Qatar, Kuwait and the UAE have approximately 493 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves. States there with official Shiite majorities, namely Iran, Iraq and Bahrain, have 252 billion barrels of proven crude oil reserves.

But Sunni-majority nations have been steadily increasing export of crude oil to the world, 11 million barrels per day in the case of Saudi Arabia, thereby depleting reserves. Production in Iraq has ramped up only slowly, since the end of Western military action there in December 2011, to 3 million barrels per day. Iran has seen its energy exports fall well below capacity during the past decade, due to mounting US and UN economic sanctions, to less than 3 million barrels per day despite locating additional potential reserves.

Likewise, the same Sunni states have approximately 41,907 billion cubic meters of proven natural gas reserves, or about 28 percent more than the Shiite states’ 32,872 billion cubic meters. Proven gas reserves in Iran are being depleted less, due to international sanctions reducing output from a high of 189 billion cubic meters in 2010, and those in Iraq are only slowly ramping up to around 140 billion cubic meters. Moreover, Iran has identified untapped potential reserves. But since 2010 both Qatar and Saudi Arabia have increased production by 11 billion cubic meters and 26 billion cubic meters, respectively, from previous total outputs of 117 billion cubic meters and 84 billion cubic meters.

So from an energy resource control standpoint, too, Shiites could make significant impacts both positively and negatively on the world’s supplies in the future. Oman has approximately equal numbers of Sunnis and Shiites – both are minorities to an Ibadi Muslim majority – and so is unlikely to be involved directly in the region’s sectarian energy politics.

Along the Persian Gulf and on the Arabian Peninsula, Sunni leaders are cracking down against Shiites seeking more proportionate benefits. Bahrain’s Sunni ruling class punishes the country’s Shiite majority for attempting a revolt while boosting Sunni numbers by recruiting immigrants. Saudi Arabia’s monarchy uses its military to enforce the regime’s authority in that country’s largely Shiite inhabited northeastern oil-rich areas and in Bahrain. In Yemen, Zaydi Shiites supported by Iran are seeking political autonomy from a Shafi Sunni government sustained by Saudi Arabia and the US. Many nations display reticence in condemning those regimes for human rights violations because the world’s economy needs Arabian crude oil. To safeguard the energy trade, American forces are based in every Sunni-administered nation in the region. British and French militaries utilize those US bases, and France has a naval facility in the UAE. As a result, Shiite hostility builds against the US and EU.

Even if the Saudis succeed in politically uniting the Arabian Peninsula, the region’s Sunnis may not be able to constrain an increasingly cooperative Iran and Iraq Shiite partnership from eventually gaining dominance. Bahrain is unlikely to remain under Sunni minority rule over the long term, and once controlled by its Shiite population will tilt toward Tehran. The same political transformation could occur in Kuwait too. Moreover, US-led sanctions against Iran will not persist indefinitely and, while they do, are providing a deferred benefit of conserving that nation’s energy resources.

Eventually in coming decades countries like Iran, Iraq, Bahrain and possibly Kuwait with large Shiite populations could well play greater roles in deciding which other nations receive much-needed energy exports —not just crude oil but natural gas—from the Persian Gulf and Arabian Peninsula. As of now the US and EU are seen by those populations as siding with their Sunni archrivals. Stability in this region depends on political power-sharing and religious tolerance between Sunnis and Shiites. The West needs to assist in ensuring those outcomes.

Jamsheed K. Choksy is professor of Iranian, Islamic, and International studies and a senior fellow of the Center on American and Global Security at Indiana University where he served as director of the Middle Eastern studies program. He also is a member of the US National Council on the Humanities at the National Endowment for the Humanities. Carol E. B. Choksy is adjunct lecturer in Strategic Intelligence and Information Management at Indiana University. She also is CEO of IRAD Strategic Consulting, Inc. This analysis is based on a study funded by the Center on American and Global Security at Indiana University. The author will field readers’ questions for a week after the publication date.