Olympics in an Age of Global Broadcasting

Olympics in an Age of Global Broadcasting

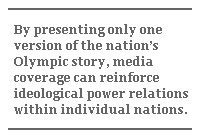

TORONTO: When the XXVIII Olympiad opens in Athens, get ready for the bursts of national pride. Since the 1964 Tokyo Games, when the Olympics were telecast live for the first time, they have become the most global sporting event in the world. Gathering together athletes and sport officials from over 200 countries as well as global corporations, the Olympic broadcast now attracts an audience of billions. Yet despite these globalizing features, the Olympics, with its televised flag-raising and national anthems for the winners, actually serves to reinforce the political and cultural distinctiveness of individual nation-states.

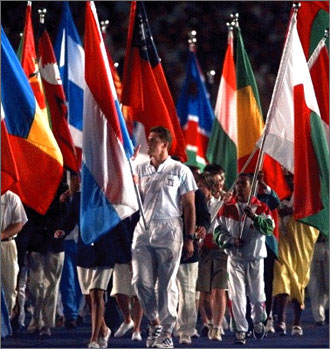

It is at international sport competitions, like the Olympics, that sentiments of national identification and belonging come to the fore in media coverage. Sporting events are one of the few public spheres where nations compete against each other without causing harm. International sport, in this context, can be seen as a substitute for war, as physical prowess becomes a measure of a nation’s standing on an international stage. The country that wins, or receives the most number of medals, is simply superior.

However, this one-dimensional perspective means that only one country can therefore ‘win’ the overall medal tally. Yet countries from around the world still manage to celebrate their Olympic athletes as national heroes. While taking images from the host Olympic broadcaster, many countries also send their own television crews to the Games to provide nationally focused commentary and discussion. Western-centered research on the Olympics and other large international sporting events (like soccer's World Cup and the Commonwealth Games) has shown that sports media coverage typically emphasises national athletes and symbols, plays up desired national characteristics, and emphasises locally-relevant rivalries in order to make the event meaningful for the viewers back home.

Each nation’s Olympic coverage focuses on its own athletes, because the media believe that is what people ‘back home’ want to see. Commentators often refer to national teams as ‘our team’ or ‘our athletes’, which reinforces for audiences that they too should be identifying with ‘their’ national representatives. As well, giving athletes or teams nicknames – such as equestrian ‘Captain Canada’ Ian Millar or the American basketball ‘Dream Team’ – further helps audiences form a connection with specific national athletes. On-screen graphics, like national flags in the corner of the screen, are also used to make Olympic coverage nationally distinct.

Every country values different qualities and characteristics in its citizens, and these transfer to national representatives. A country’s general sense of its place on the world stage, in combination with desired traits, will shape the Olympic broadcast in that nation. For example, New Zealand, as a small country, is highly unlikely to win more medals than China, Germany, or the United States. So the New Zealand media tend to downplay success as the sole factor in evaluating their athletes’ performances. Instead, their coverage emphasises how hard the athletes have trained, their ‘good sports’ ethic, and the value of simply participating and sharing in such a wonderful event. These characteristics reflect the qualities desired in ‘typical’ New Zealanders who give their all. By highlighting the intrinsic elements of athletic performance, the New Zealand media reduce the risk of embarrassment if the athletes fail to perform. If the athletes do win, their success can be celebrated as a bonus.

In contrast, Australia’s Olympic coverage emphasises winning. Although Australians are unlikely to top the overall medal tally, winning more medals than specific rivals is of paramount concern. Beating the United Kingdom plays an essential role in confirming Australia’s national identity by proving it has overcome relatively humble beginnings as a British penal settlement and colonial outpost. Surpassing the performance of colonial neighbour New Zealand is taken as a given although rivalry in certain sports, such as equestrian and rowing, is still strong. Today, the main rivalry for Australians is the United States, especially in swimming. Success in the pool marks Australia as unique in the face of an increasingly American-dominated national and popular culture.

Countries that are geographically close, have co-dependent economies and/or political allegiances also use sporting competitions as a means of ensuring cultural distinctiveness. However, it is typically in countries under ‘threat’ from these globalizing forces that events like the Olympics take on greater national significance. The cultural value and importance of Olympic sports that embody the determined nature of Canadians is indicated by the extensive public demonstrations of national pride following victories over their neighbour, the United States. After Canadian victories in the ice hockey competitions at the 2002 Winter Olympics, flag waving, wearing ‘Canada’ t-shirts, street parties and parades were common. In contrast, the United States, as an already established cultural, political and economic leader, has relatively less to gain from successful Olympic performance in terms of building national identity and pride. Indeed, the United States appears so secure in its place as a world leader, that participating in localised and internally-focused sports like Major League Baseball, NBA Basketball, and NFL Football is enough to reinforce key national values such as success, athletic mastery, and upwards economic mobility.

While media coverage of the Olympics emphasises difference between nations, it can also narrow the definition of what it means to belong to a particular nation and further undermine the Olympic rhetoric of uniting people. By presenting only one version of the nation’s Olympic story, media coverage can reinforce ideological power relations within individual nations. An example is broadcasts that focus on the athletic achievements of male athletes, and the domestic roles (wife/mother/daughter) of female athletes. Different reporting styles for male and female athletes can reinforce cultural ideas about gender difference rather than focusing on the shared physical and mental abilities needed to become the best in the world. In addition to gender, sports media coverage can also emphasise preferred cultural values of class, race, sexuality and dis/ability.

When sports performances are deemed to have extraordinary political, cultural or economic significance, internal national divisions may be overridden in coverage of high profile, successful, individual athletes. At the Sydney 2000 Olympics, the performance of Indigenous Australian 400-metre runner Cathy Freeman was tied to the contentious political issue of progress on Aboriginal reconciliation. Freeman was presented by the media as a person who could unite Australia through athletic success, and this unity could then be transferred to political pressure on the Australian government to apologise for past injustices to Indigenous peoples. In this instance, Freeman’s status as a symbol for national unity and reconciliation appeared to negate her ideologically subordinate positions of being female and Indigenous.

It is clear that the Olympic sports media context is important for maintaining and constructing the collective identity of individual nations. Sports media coverage helps nations define themselves as unique, whether through success or the valuing of particular characteristics. In addition, commercial pressures to provide large audiences for Olympic and broadcast sponsors means that local broadcasts will be tailored further to increase the meaningfulness of the event for particular national audiences. In this way, Olympic broadcasting is simultaneously tied to both the local and the global contexts. As the Olympics are staged over the next two weeks, watch cautiously and think critically about the way the broadcast is shaped for your particular national audience. Remember that what you are watching is not just athletes competing, but a carefully planned and managed television product designed to keep you interested by reinforcing where your allegiances should lie.

Emma Wensing is a PhD candidate in the Faculty of Physical Education and Health at the University of Toronto. Information in this article is drawn from her Masters thesis and research on media representations of Cathy Freeman conducted with Toni Bruce (University of Waikato, New Zealand).